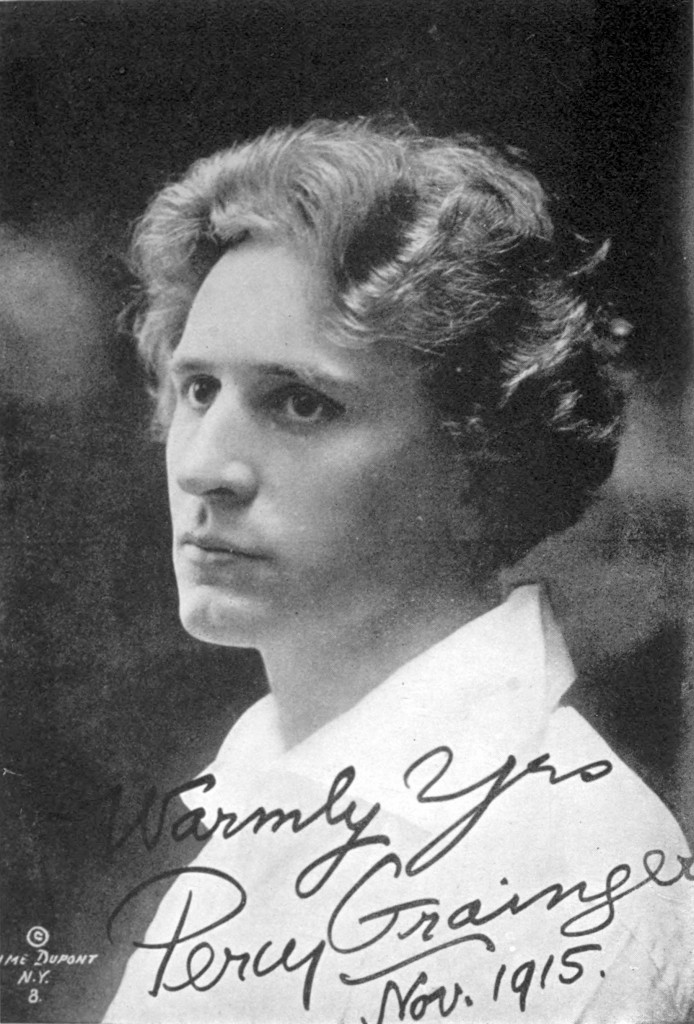

A musical and sexual adventurer, a racist for show or for real, and a composer ahead of his time in promoting his innovations in ‘free music,’ Percy Grainger called himself an ‘aesthetic failure’ shortly before he died in 1961. A new album of Grainger works by the Bilder Duo is cause for reconsidering a most unusual life and career.

Australian-born pianist and composer Percy Grainger was one of the major eccentrics of music history. His foibles were legendary: backpacking to concerts, sleeping on top of closed grand pianos as an audience entered the hall, declaring himself publicly as an avowed devotee of sadomasochistic frolics, and getting married at the Hollywood Bowl before an audience of 20,000. When he went looking for a home in Westchester County in 1921, he bought an old house in White Plains that looked like a backdrop for a Hitchcock film. He hobnobbed with Delius and Grieg, developed “free-music” theories and experimented with the theremin.

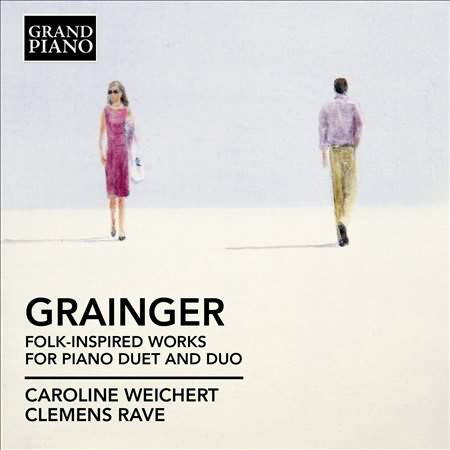

Grainger: Folk-Inspired Works for Piano Duet and Duo, a new album from the impressive Bilder Duo, a young ensemble consisting of German pianists Clemens Rave and Caroline Weichert, is an occasion to reconsider Grainger’s fascinating music and colorful life.

As a gifted keyboard virtuoso, Grainger wholeheartedly embraced the Romantic art of transcription. The beloved favorites are accounted for in the Bilder Duo’s new work, including “Molly on the Shore,” based on a playful Irish reel, and “Country Gardens,” his most popular work. More stately material also turns up, including “Horkstow Grange (The Miser and his Man)” from Lincolnshire Posy, which has a majestic and tranquil nature common to British folk music. In a grandiose “Fantasy on Porgy and Bess” Grainger channels several of Gershwin’s piano works, providing the album with a rousing climax.

From a strictly musical standpoint, Grainger’s career is succinctly summarized in Classical Archives.com:

Percy Grainger was known during his lifetime as a virtuoso pianist and arranger of popular English folk song. His primary contribution to music, however, lies in his prolific output as a composer of expert and highly original works. Grainger’s early years were spent in Melbourne, Australia, where he studied first with his mother, and later with Louis Pabst. From 1895-1899 he attended the Hoch Conservatory in Frankfurt, Germany, and then settled in London in 1901. The next 10 years or so were devoted to a combination of concert touring and folk song collection. Grainger’s early reputation was as a brilliant and eccentric pianist, and it was this talent that not only provided his income for the rest of his life, but also brought him into contact with other composers. Grieg and Delius, in particular, had great influence on Grainger’s development of a sympathy and sensitivity toward unique national and folk styles. In 1914, Grainger moved to New York, beginning a long career as a composer, arranger, collector of folk music, and educator; he became an American citizen in 1918. In 1925 and 1927 he collected and published over 200 Danish folk songs, and returned to Australia in 1924, 1926, and from 1934-1935 in order to establish a Grainger Museum at the University of Melbourne devoted to ethnomusicological research. His final years were spent completing and arranging his earlier works and trying to develop a workable form of his “free music” using primarily theremins, one of the earliest electronic instruments. The project remained incomplete, and Grainger died embittered and in relative obscurity, known only for a handful of light works that he referred to derogatorily as his “fripperies.”

Percy Grainger plays his most famous composition, ‘Country Gardens,’ on a 1929 Steinway Duo-Art Player Piano

Alfred Hickling, writing in The Guardian of November 10, 2011, added a valuable perspective on the composer he declared to be “unaccountably odd.” Notes Hickling:

It is hard to conceive how great a celebrity the Australian composer, pianist and folk-song collector once was. Widely acclaimed as one of the most gifted concert pianists of his generation, he earned the equivalent of £60,000 per week, befriended Grieg, Gershwin and Duke Ellington and got married on the stage of the Hollywood Bowl before an audience of 20,000. Yet Grainger, born in Melbourne in 1882, never quite lost the taint of an outsider–a loose cannon whose personal eccentricities threatened to overshadow his achievement.

Grainger was, by any standard, unaccountably odd. He favored garish, towelling outfits of his own design, was known to mount concert platforms at a running leap, and pushed his favorite piano stool round in a wheelbarrow. In 1945 he devised his own composer-rating system and ranked himself ninth, below Delius but above Mozart and Tchaikovsky. He placed Bach the top of the list because “if he were living today, I feel Bach would include ragtime, Schonbergism, musical comedy, Strauss and all the grades in between.”

Percy Grainger plays Grieg’s ‘Peer Gynt Suite No. 1, Op 46, ‘Morning Mood.’ From a Duo-Art Reproducig Piano Roll #A-57.

Practically all of Grainger’s compositions are miniatures, between two and eight minutes in length, and often feature unconventional forces such as harmoniums, banjos, theremins and ukuleles. His disdain for classical form extended to a rejection of Italianate terms for tempo and dynamic markings–Grainger’s scores indicate “louden” rather than “crescendo,” or instruct the player to interpret a passage “with pioneering keeping on-ness.” His rejection of the symphony, sonata and concerto was deliberate, but contributed to the impression that he was merely a dilettante or a purveyor of light music.

The Northumbrian pipe player Kathryn Tickell challenges this. “I think anyone who considers Grainger’s music lightweight simply lacks the imagination to perform it the way it was conceived,” she says. “The trouble is, he became his own worst enemy where posterity is concerned. There are very few orchestras able to bring in a bass concertina or a detuned guitar for a piece that lasts maybe a minute-and-a-half.”

“I’m usually quite suspicious about classical composers who impinge on the folk world,” Tickell says. “But Grainger is different. He collected all the difficult tunes that no one else wanted to set. Shepherd’s Hey, for instance, is a bit of a dirge, but he transformed into something so life-affirming it makes you want to shout. But he never sought to prettify the material or make it polite. His Lincolnshire Posy suite was arranged for a military wind band, yet it still sounds like folk music. He recognized the songs for what they were–tales of poverty, vitality and survival.”

Grainger was the first to use a phonograph to record folk songs, and held untutored musicians in high esteem. “These folk-singers were the kings and queens of song!” he declared. “No concert singer I ever heard, dull dogs that they are, approached these rural warblers in variety of tone quality, range of dynamics, rhythmic resourcefulness and individuality of style.” In 1912, he travelled to the Pacific islands to notate native songs whose random combination of musical elements anticipated John Cage’s experiments in “chance music” by some 40 years.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8nxaNJCfGCo

‘Hordstow Grange,’ the second movement from Percy Grainger’s ‘Lincolnshire Posey,’ performed by the North Texas Wind Symphony

‘Rufford Park Poachers,’ the third movement from Percy Grainger’s ‘Lincolnshire Posey,’ performed by the University of Illinois Symphonic Band, Dr. Harry Begian, conductor.

The ‘grandly rhetorical’ ‘Lord Melbourne,’ the fifth movement from Percy Grainger’s ‘Lincolnshire Posey,’ performed by the University of Illinois Symphonic Band, Dr. Harry Begian, conductor.

‘Grainger’s ultimate masterpiece in this vein [embracing folk material within a classical baroque convention] is probably A Lincolnshire Posy, a suite of six Lincolnshire folk songs arranged for wind band, but also existing in a version for two pianos. Here the folk past and the immediate present are inextricable, art and action being transcended. The ‘pastness’ of the tunes becomes unpredictable, and old music proves newly fertile: especially in the heroically bitonal Horkstow Grange, the large-scale, dramatically developed Rufford Park Poachers, and the grandly rhetorical Lord Melbourne. A Lincolnshire Posy was composed in 1905, before Grainger became an American citizen; but it is a harbinger of his last years in that it so brilliantly syphons new wine into old bottles–as well as being scored for that American institution, the collegiate wind band.’ –Wilfrid Mellers.

Grainger spent his latter years in pursuit of an entirely new way of composing. According to Hickling, he believed western music “to be arrested at a state similar to the two-dimensional artifice of Egyptian sculpture, and spent his latter years attempting to construct a machine capable of generating scaleless, pulseless, synthetic sound which he termed ‘Free Music.’ The various prototypes were among the earliest attempts to build a synthesizer, and though Grainger’s ambitions outstripped the available technology, he would no doubt be delighted to find that YouTube now hosts examples of his Free Music adapted for iPhone.”

Restless with the status quo, Grainger absorbed everything around him—“his musical canvas became a vast, virgin territory open to all outside influences,” Hickling says, noting that the composer may well have been the first to equate the importance of a jazz band with that of an orchestra, “that a squeeze box could be as expressive as a grand piano, and to prefer playing in cinemas to concert halls.

“Above all,” says Hickling, “he believed that music was a universal art: ‘As a democratic Australian, I long to see everyone somewhat of a musician, not a world divided between undeveloped amateurs and overdeveloped musical prigs.’”

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bWgwPpb42kM

Percy Grainger’s ‘In Dahomey (Cakewalk Smasher),’ played by Marc-Andre Hamelin. ‘In Dahomey (1903-09) doesn’t use real folk tunes but is based on American minstrel show music, cakewalks and ‘coon band contests.’ Ear-boggling in virtuosity, this rip-roaring fiesta is corporeal action, which needs a generous sprinkle of wrong notes for maximum effect.’ –Wilfred Mellers

Then there was Percy Grainger’s dark side, which he pretty much paraded before the public. Consider this addendum to a profile of Grainger at the Bach Cantatas Website:

His music aside, he remains controversial on two accounts. First, Grainger was an enthusiastic sado-masochist. Second, he was a cheerful believer in the racial superiority of blond-haired and blue-eyed northern Europeans. This led to attempts, in his letters and musical manuscripts, to use only what he called “blue-eyed English” (akin to Anglish and the ‘Pure English’ of Dorset poet William Barnes) which expunged all foreign (i.e. non-Germanic) influences. Thus many Grainger scores use words such as “louden,” “soften,” and “holding back” in place of standard Italian musical terms such as “crescendo,” “diminuendo,” and “meno mosso.”

This racial thinking (with its concomitant overtones of xenophobia and antisemitism) was, however, inconsistently and eccentrically applied: he was friends with and an admirer of Duke Ellington and George Gershwin. He eagerly collected folk music tunes, forms, and instruments from around the world, from Ireland to Bali, and incorporated them into his own works. Furthermore, alongside his love for Scandinavia was a deep distaste for German academic music theory; he almost always shunned such standard (and ubiquitous) musical structures as sonata form, calling them “German” impositions. He was ready to extend his admiration for the wild, free life of the ancient Vikings to other groups around the world, which in his view shared their way of life, such as the ancient Greece of the Homeric epics.

Ella Strom Grainger, Percy’s wife and willing participant in his sadomasochistic revelries. In a letter titled ‘Read This If Ella Grainger or Percy Grainger Are Found Dead Covered with Whip Marks,’ the composer wrote: ‘I am a sadist & a flagellant–my highest sexual delight is to whip a beloved woman’s body…To a lesser degree I enjoy being whipped myself (& before marriage used to whip myself every few weeks)…’

As for his appetite for flagellation , he was encouraged in its pursuit by his wife Ellas, a willing participant in his revelries. The composer donated his collection of whips and other paraphernalia to a museum he established (the Grainger Museum in Melbourne, still in operation, which he opened as part of his fervent aim to be recognized as Australia’s first significant composer—even though he left the continent as a teenager and spent most of the rest of his life in London and White Plains, NY, just north of New York City) and discussed his passion for flogging in a manner admirably free of shame or neurosis. “I am a sadist & a flagellant–my highest sexual delight is to whip a beloved woman’s body…To a lesser degree I enjoy being whipped myself (& before marriage used to whip myself every few weeks)…” These observations were contained in a letter titled “Read This If Ella Grainger or Percy Grainger Are Found Dead Covered with Whip Marks.”

Percy and Ella Grainger at the Grainger Museum in Melbourne, 1956.

This letter is contained in Self-Portrait of Percy Grainger, a posthumous collection of the composer’s writings, some of which were dashed off as asides while others were notes for an autobiography left uncompleted at his death. The personality that emerges is obsessive, irascible and–above all–mother-fixated. Pieces like “Arguments with Beloved Mother,” “Mother’s Worship of Bodily Beauty” and “Mother’s Wilfulness, Recklessness, Fearlessness, Bossiness, Violence if Opposed, Tendency to Burn Food When Cooking, Vehemence” speak of an obsession of Norman Bates proportions. His first known composition, in fact, was “A Birthday Gift to Mother,” dated 1893.

Mother Rose Grainger with son Percy. He declared her suicidal leap from a 42nd Street skyscraper in New York City to be a ‘Nitzschean’ act. He wrote a piece about her titled ‘Mother’s Wilfulness, Recklessness, Fearlessness, Bossiness, Violence if Opposed, Tendency to Burn Food When Cooking, Vehemence.’

Rose Grainger, his mother, was, however, beset by mental problems. In 1922 she took her own life by jumping from the 18th story window of the Aeolian Hall Building on W. 42nd Street, landing on the roof of an adjoining building. “This was the defining event in Grainger’s life,” writes James Conway at the Strange Flowers blog, February 20, 2011. “Although a few years later he was positing the theory that it was in fact a ‘Nietzschean’ act: ‘She saw (I think likely) me as the younger, superior, healthier, more gifted one, saw herself as the older, weaker, inferior one, thinking her mind was going.’ In fact, his mother had been disturbed by rumors that she was involved in an incestuous relationship with her son. Though false, you could see how Percy’s habit of parading nude in his mother’s presence well into adulthood might have nudged others to that conclusion.”

Adds Conway: “The early 20th century was a golden age of pseudo-science, and Grainger was a keen reformer in his dietary and other lifestyle choices, and an admirer of early self-help guru Bernarr Macfadden. But as his callous, narcissistic theory about his mother’s death shows, this can lead to dark places. The idea of eugenic sacrifice recurs in another passage, in which Grainger appeals ‘Let us set our house in order–kill off the sick, the nasty, the ugly, the lazy.’ Delve even further into Self-Portrait and you enter the kind of territory normally explored in late night talk radio. A fervent racist, Grainger regarded Scandinavia as the wellspring of all that was good and right, his scorn for other ethnic groups—‘the hostile world of rough, harsh dark-eyed people’–increasing in reverse proportion to degrees of latitude. And the older he got the more cantankerous he became. A 1958 piece entitled ‘The Things I Dislike’ began ‘Almost everything. First of all foreigners, which means: all Europeans except the British, the Scandinavians & the Dutch.’”

Not content with merely distrusting anything originating south of Holland, Grainger sought to purge his writing of Greco-Latin elements, which were isolated in double brackets, introducing a kind of apartheid into his very sentences. He sought alternatives for these quarantined interlopers based on Nordic roots (much as the Nazis would later seek to purge French vocabulary from German). And so family became “breed-group,” literature became “book art” and attractive became “on-draw-some”; Grainger called the resulting mishmash “Blue-Eyed English.”

Yet opinion is divided as to how seriously Grainger took his own rantings, given his friendships with musicians of all races and creeds, and his enthusiasm for music of other cultures. Some critics have posited that his offensive rants were more show than deeply held beliefs, although that hardly diminishes the repugnance of those ideas. But Grainger himself never let on that this side of him was all performance art, so pending new revelations to the contrary, he is judged by what he said for the record. His life and career truly embody Pete Townshend’s maxim to “trust the art, not the artist”—and the art is often as breathtakingly beautiful and soulful as its daring is impressive. Sadly, as he lay dying of cancer in 1961, Grainger felt all his efforts had been for naught, that he was forgotten, not even a footnote in the musical history of his time. “All my compositional life I have been a leader without followers,” he wrote. “Where musical progress and compositional experiment are discussed, my name is never mentioned. Can a more complete aesthetic failure be imagined?”

The composer who would not brook anyone telling him he was wrong could not have been more off base as he drew his last breath.

(from left) Edvard Grieg, Percy Grainger, Nina Grieg and Julius Röntgen in the garden, Troldhaugen, Bergen, Norway, 1907. (Photo: Bergen Public Library Norway)