‘I will not stand by and watch the complete abomination of our limited natural communities’

Henry David Thoreau speaks of the month of January explaining that, “All nature is but braced by the cold. It gives tension to both body and mind.” On a sunny, pleasant day in January, the farmers that bought the land to the north of the beautiful wooded neighborhood where I live decided that the immediate “profit” of cornfield outweighed the value of 11 acres of old growth woodland. The 11 acres that lies on their side of the fence is attached to a continuous 93 acres of oak and hickory forest; the nuts and acorns that descended on our side of the fence couldn’t possibly know how fortunate they are to have fallen just a few feet farther than their brethren.

In Winnebago County, Illinois, 93 acres of private forest land is very rare and it is an honor to live amongst these trees. As I stand on the deck of my home, a spectator watching another 11 acres disappear, two great horned owls echoed my feelings of sadness. I hope my owl friends find refuge in our shrinking woods. My three-year-old son, Ely, and Ely’s children will be the ones who lose out. More than ever, I see the importance of protecting our precious natural resources. Let these pages be read with the understanding that the effects of our decisions far outreach the borders of our properties.

‘Two great horned owls echoed my feelings of sadness. I hope my owl friends find refuge in our shrinking woods.’

In 1980 at a gathering of farmers, Nina Leopold Bradley had a conversation with an Iowa farmer in which the farmer indicated that the government “seldom acknowledges good farmers, either financially, politically, or socially.” Even within the farming occupation there is a division, plotting “good farmers” against “bad farmers.” “Good farming” is farming that is beneficial to the community by producing both commodities and public goods. I myself come from a farming family and some of the people I care the most about have made decisions that may not have been the most responsible or ethical as caretakers of the land.

Having grown up with “dual citizenship”–that is, one foot rooted in the family farm, and one foot planted firmly in environmental conservation–I have developed my own definition of the farmer: anyone who has the opportunity to make decisions that impact the health, conditions, and functions of land. These decisions that affect our landscape, so paramount to our existence on this earth, must be deliberated carefully, weighing every option till exhaustion. The land deserves it. So does the future. A quick decision is almost always a costly decision, far exceeding the momentary flash of dollars in the bank. Land is our great investment. All I ask is that we consider the opportunity cost when making long-term decisions that look good on paper and fatten our bank accounts, but do little to enhance the beauty in our communities. This lack of forethought is stealing from the future. There must be others who agree that a few more rows of corn now are not a compromise worth this cost.

Compromise is a word casually tossed around when two heads are struggling over one voice. As I write about “bad farmers,” let me be clear that I do not hate farmers. I am merely pointing out the sometimes antagonistic relationship that exists between agriculture and conservation. I acknowledge the fact that farming is necessary, and I am not arguing against the growth of food. But I will not stand by and watch the complete abomination of our limited natural communities. Even in the near future, children will have no real gains from 20 more rows of corn; they will not be able to run free through the rows of soybeans, jump over non-existent wildflowers, or build forts amongst the ears of corn. They will not enjoy the songs of wood thrush and warblers that have long disappeared, their songs replaced by the roar of diesel engines and then silence once the machine has passed. This corn desert is becoming far too familiar a scene throughout the Midwest and has led some to term our very own backyards as ecological sacrifice zones. Is this the community we are comfortable living in? Is this the community we would like to leave our children? Scott Russell Sanders states, “If we hope to survive on this planet, if we wish to leave breathing room for other creatures, we must learn restraint, learn not merely to will it, but to desire it, to say ‘enough’ with relish and conviction.”

‘Even in the near future, children will have no real gains from 20 more rows of corn; they will not be able to run free through the rows of soybeans, jump over non-existent wildflowers, or build forts amongst the ears of corn. They will not enjoy the songs of wood thrush and warblers that have long disappeared, their songs replaced by the roar of diesel engines and then silence once the machine has passed. This corn desert is becoming far too familiar a scene throughout the Midwest and has led some to term our very own backyards as ecological sacrifice zones.’

Farming is not what we once knew. Since 1850, the Census definition of a farm has changed 10 times, but has our view of farming changed 10 times? Do we, as a primarily urban civilization, picture a farm as a romantic scene of Americana? A tall red barn sits on a hillside with a stone silo standing to the west, casting a shadow onto the beautiful orchard, trees ripe with fruit. Green grass surrounds a two-story house, which is wrapped by a covered porch with beautiful flower baskets hanging from the eaves. Mother is sitting in a rocking chair knitting while supper warms on the stove. Little ones with grass-stained jeans and dirty elbows are playing baseball in the yard. Pa and the eldest sons come in and enjoy supper while sharing stories of how the prized cow kicked the pail over, but what a gift the spilled milk is to the barn cats. Walking up the old farm road, two young girls with baskets of eggs look out over fields lined with picket fences and filled with crops of assorted vegetables–a forecast of a bountiful harvest. Deer and turkey feed under the oaks, and the family talks about what to wear to church that evening. The American dream is a beautiful scene and enduring to our spirit. These days, whether they truly ever existed or not, are assuredly gone, and reality is not nearly as attractive.

Industrialized corporate farming techniques have altered the structure of agriculture and therefore our communities. The definition of farm now centers on monetary production; according to the USDA Economic Research Service, “Agricultural production is a major use of land, accounting for around 51% of the U.S. land use.” Gargantuan, heavy, loud machines thunder through miles of monoculture crop. A GPS, not a farmer in bib overalls, guides it mindlessly over the land. Today’s farmers rarely see their families, as the opportunity to buy, lease, or work thousands of acres takes them further and further from their homes. Does this sound like a romantic scene?

Examples of community detriment as farms have changed from self-sustaining family operations to the homogenous large cash crop farms are evident here in northern Illinois. There are many studies that support the hypothesis that growth of large farms and/or decline of moderate-sized farms adversely affect communities. Have you seen this in your rural communities?

While growing up, the sign coming into the village where I lived read: “Population: 800.” The lyric “where everybody knows your name” is the perfect description of my childhood. My predecessors arrived in 1840 and helped lay the foundation for what eventually was known as the village of Winnebago; one of a million Midwestern towns who named themselves after the peoples displaced by “progress.” There were 1,000 or so on the sign by the time I was in school and in these early years I learned quickly that I was a part of the community. The church and schools were full of people who knew my name and more about me than I did. I bore a strong resemblance to my Uncle Matt, twenty-some years my elder, and therefore teachers would often call me Matthew.

I was bound by this community, and never wanted to do something that would disappoint my family. I felt safe being a part of a community. The community helped shape who I would become: a child reared in an environment not just by a loving family, but also the community as a whole. This to me seems obvious as a productive means to co-exist. The community invests in each other, knows each other, and cares for each other, therefore raising children who, for the most part, want to continue the pattern. The pattern of course collapses when the export of resources, natural (such as timber, food, water, etc.) or personal (such as emigrating families and young workers), exhausts the communities’ ability to keep up with demand. The farmer, who before could sell his milk and crops for enough to feed his family and give his offering at church, cannot subsist any longer. The same farmer could have spent a day of the week on his “back 40” watching warblers migrate through autumn leaves or spend time watching his children grow. Now to keep up with the unattainable desires from outside the community, the farmer has to make the choice to sell his land and find his living elsewhere, or worse as is most often the case, abuse the land to wring every last penny from it.

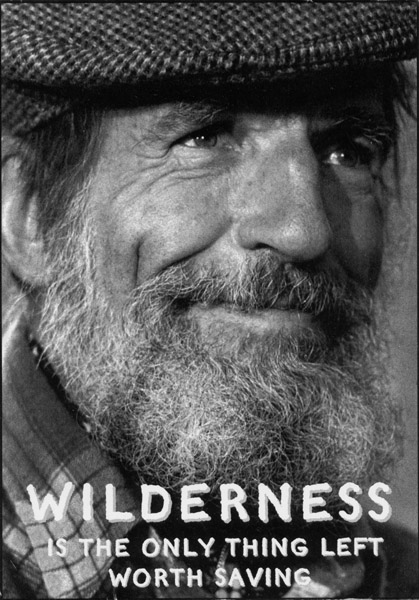

One of my favorite Ed Abbey quotes describes the mindset of my new neighbors in the woods: “I have been called a pioneer. In my book, a pioneer is a man who comes to virgin country, traps off all the fur, kills off all the wild meat, cuts down all the trees, grazes off all the grass, plows the roots up and strings ten million miles of wire. A pioneer destroys things and calls it civilization.” This isn’t neighborly behavior or behavior beneficial to the health and function of our community.

Ed Abbey: ‘I have been called a pioneer. In my book, a pioneer is a man who comes to virgin country, traps off all the fur, kills off all the wild meat, cuts down all the trees, grazes off all the grass, plows the roots up and strings ten million miles of wire. A pioneer destroys things and calls it civilization.’

It is April now and the woods to the north have been sliced in half with methodical precision. We bought Ely his very own trowel that was the perfect size for his three-year-old hands. Loaded up with five-gallon buckets and our shovels, we started the mission of the day. My wife Emily, Ely, and myself headed down the lane to the “bad farmers'” territory. To our shock and disgust, the gullies and trenches left behind from the heavy machinery savagely raping the old growth oak woodlands was surging with life in one last attempt to see the sun. Trilliums, trout lily, ginger, blue cohosh, bloodroot, and cut-leaved toothwort were the few species I could find. As we filled buckets with the Northern Illinois native plants, I tried to take soil that may hold jack-in-the-pulpits, may apple, and countless other woodland wildflowers that won’t have even awakened before the tractor pulls a ripper through as the final blow to this ecosystem. The sweat dripping down my back and the pain in my hands from digging and hauling buckets is nothing in comparison to the ache in my soul. Their myopic viewpoint stretches only as far to see the money in the bank. I wish they knew the long-term effects of their greed. This acreage will never again be remnant oak woodlands with a showy ephemeral flower burst to be enjoyed each spring. Now it joins the billions of acres around it, and every spring the smell of wet soil will be the only appeal to the senses before yet another row of corn is planted.

This day of witnessing such colossal environmental degradation invoked my own personal land ethic, which has been built through my own farming background, my education in natural resources, and my life experiences simply enjoying nature. Part of this ethic revolves around a conversation I once had with my Uncle Mike, who was the owner and manager of our family farm. He was a brilliant man who was passionate about his work, and the words we spoke a decade ago still linger in my mind clearly today. Having just graduated college, I was full of ambition, hope, and arrogance. My conversation with Uncle Mike started off about the farm and its wetlands and woods, CRP programs, and so on. I wasn’t telling Uncle Mike anything he didn’t already know, but he was nothing if not a family man, so he let me blabber on and on and say my piece. After I finally ran out of words, he looked me in the eye. His glasses were dark, a dirty ball cap covered his hair, and a thick black beard peppered with grey covered his face. He had strong forearms from the years of carrying buckets of water and grain, a silver watch, blue jeans, and brown boots. He spoke softly, but without hesitation, and told me that we honor our ancestors by farming the land they homesteaded. It would be a slap in their face to replant the woods that they worked so hard to clear. He turned and silently walked into the milk parlor.

He was right. Almost always was. Our ancestors cleared the land because they had to; not because they wanted to, but because it was the only option for survival. They had to squeeze a life out of land they didn’t understand with only the knowledge and technology brought on covered wagon. To do what it takes to survive is a bold blanket statement open to an endless amount of interpretation and justifications. Everyone’s concept of survival is different, all skewed by the same demon–that survival eventually becomes surplus, and surplus evolves into greed.

The groaning of the articulated tractor constantly humming in an endless drone becomes almost white noise in our neighborhood. That’s what they are hoping for, “they” being all the destroyers. They want us to become so accustomed to their actions it becomes our everyday soundtrack. Destruction right in front of us that we don’t see is exactly what they need.

Now it’s July, and two young men, one appearing to be just a teenager, have arrived with chainsaws. They see me here watching. As the bulldozer devours the understory, the operator barely has to raise the engine past idle to easily topple young trees. Humans effortlessly destroy. To create takes work–hard work–but to destroy merely means the turn of a key. They rev their saws, and the younger one fingers the trigger, looks at me, and then lets the engine scream. They know what they are doing is wrong, but they are just kids employed to destroy. He is wearing no personal protection equipment at all; admittedly I envision the chain flying off and ending his fun. Chainsaws scream, the tractors roar, trees snap. Trees waving wildly as the beast slams into old-growth oak, squirrels, birds all flee. Unlike a flood or fire, the animals can never return.

‘The groaning of the articulated tractor constantly humming in an endless drone becomes almost white noise in our neighborhood. That’s what they are hoping for, ‘they’ being all the destroyers. They want us to become so accustomed to their actions it becomes our everyday soundtrack. Destruction right in front of us that we don’t see is exactly what they need.’

This magnitude of destruction is glacial disturbance, leveling a landscape and erasing an ecosystem. If this chainsaw-wielding young man makes it to adulthood and has children of his own, will he bring them here to walk amongst the corn? Every tree that is not sellable to the mill as lumber is being shredded. I can hear the roots tearing; sometimes the young oaks that already have an incredible taproot hold tight to the earth. Millions of microscopic root hairs versus a 13-ton W130 New Holland: the winner each time is the hulking machine. When the taproot breaks free, it nearly breaks the sound barrier. The slash and rubble is pushed into large burn piles where a claw machine beats the soil from around the root balls so it can be hauled away on semi-trucks. The wind swirls very lightly today, yet dust devils whip up easily in the dry silt and carry away even more of the soil.

We all agree greed is ugly, yet not one of us can resist the urge to be ugly. I am not going to try and understand or explain greed or why humans have evolved to be themselves greedy. We just are, but we are also caring, compassionate, and all other virtues opposite of greed. Psychiatrist Carl Jung stated, “The psychic depths are nature, and nature is creative life. It is true that nature tears down what she has herself built up–yet she builds it once again.” Expounding on human mindsets he goes on to say, “The psyche is a self-regulating system that maintains itself in equilibrium as the body does.”

Why is it that some of us can have empathy for non-human species, both flora and fauna, and others can push a forest over, or rip the head off a mountain, or strangle a river dead then sleep at night? Because those that destroy are bullies. Bullying is defined when someone, persistently over a period of time, is on the receiving end of negative actions from one or several others, in a situation where the one at the receiving end of the actions for different reasons may have difficulties defending him- or herself against these actions.

This is how we treat nature. We all learned along the way that the best action against a bully is to stand up against them. I’m not saying physically, although there are times it’s the only way, but by exposing them for what they are. A bully’s greatest weapon is fear. Not the fear inflicted upon the victim, but in the fear they invoke in the witnesses. This fear of being the focus of a bully creates silence and inaction. That is just what the bully wants and needs to continue. A bully is only strong if those of us watching are so stricken with fear that we become cowards. What is worse–being a bully, or allowing bullying to continue?

Nature is defenseless with one exception–you. If I can inspire enough of “You,” WE can be powerful, WE can make change. This is nature’s only hope. To stand up against nature bullying is going to take action, it’s going to take sacrifice, and it will be a long journey. The fight will be intellectual, and the fight will be emotional with the “cooler head” prevailing. It happens by changing relations within our communities, by knowing our neighbors and investing in long-term commitment to the health of our habitat, our land. The very base of life, human and non-human, is our habitat–land’s true value. Elementary students can answer the question, “What makes a habitat?”: food, water, and shelter.

I recently read a report published by the USDA entitled, “The Use of Markets to Increase Private Investment in Environmental Stewardship.” It states, “Without well-defined markets for environmental services, landowners are not rewarded financially for supplying them. For example, without a market for environmental services a farmer with native vegetation on his or her land has no economic incentive to preserve the cover and the environmental services it provides.” The Economic Research Service tracks conservation program funding levels and analyzes program design features that increase environmental gain per program dollar. I read through the “Green Payments” and “Incentives for environmental compliance” sections in disbelief. When land is sold its value as anything but investment diminishes. The “sense of place” is lost as land becomes just an asset. We need Aldo Leopold now it seems more than ever. I am glad we have programs and land protection laws, but should we need them? What happened to the land ethic?

Why does there need to be an incentive to preserve our greatest investment? I couldn’t agree more with Leopold when he stated, “It is inconceivable to me that an ethical relation to land can exist without love, respect, and admiration for land, and a higher regard for its value. By value, I of course mean something far broader than mere economic value; I mean value in the philosophical sense.” He also stated, “A thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability, and beauty of the biotic community. It is wrong when it tends otherwise.”

Aldo Leopold, father of conservation ethics: ‘A thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability, and beauty of the biotic community. It is wrong when it tends otherwise.

’Have we as a society forgotten or chosen to no longer hear Aldo’s words? We need Aldo’s voice, one that speaks to the landowner as a landowner. Unlike any other environmental conservationist, Leopold can relate to and express the concerns of the landowner. He speaks of a balance. The human experience strives for balance; consciously with every step we take, and unconsciously with every hormonal secretion that keeps us alive. When we get out of balance, we fall and sometimes we struggle to get back up. We need balance, not just in ourselves but also in our surroundings. Nature is balance in form and function.Eight months after the first tree was felled on a warm evening in August, Ely and I wandered onto the “bad farmers'” land to pay our respect to the last of the lone soldiers left in the woods. Walking through the torn woods, Ely and I walked up to a titanic old oak, and without my prompting, Ely reached his little arms around, hugged it, and with tears in his eyes and trembling voice, told the tree that he wished he could pick it up and carry it to our yard where it would be safe. This moment has enraged me. How is there not more protection for systems on private land? What they are doing is immoral and they know it. That’s why they are obliterating the woods at break-neck pace, even going so far as to pulverize the soil and erasing the existence of anything. They are trying to make it easier to forget that woods ever existed. I will never forget.

I work at Severson Dells Nature Center, a non-profit outdoor education facility tucked inside a county forest preserve. My title, Environmental Educator/Biologist, allows me the greatest joy of sharing my passion with others and turning my hope into action. In September, a group of second graders that I was lucky enough to share my day with filled me with hope, a true, deep, real hope. They were all enthusiastic rural children who remarked without encouragement about their love and connection with nature. This gave me hope. As we walked the trail, it had never taken me so long to reach the pond, which is normally a 10- to 15-minute walk. This time not one leaf was passed without inquisitive wonder; no walnut, hickory, or acorn was passed without a moment in the spotlight. This gave me hope.

Upon reaching the pond, these second graders couldn’t corral their excitement when a small painted turtle was spotted basking on a log. “Mr. K! Mr. K!” a little girl with a floppy hat called out while hopping up and down. “Did you know turtles are reptiles and they have cold blood so he needs to sit in the sun to warm up?” Another little boy responded, “It is probably trying to get energy to eat, we should let him be.” Then with my lower jaw still comically ajar with amazement, 13 children tiptoed away to let the turtle bask. This gave me hope.

As we walked farther along the trail and deeper into the woods, a young girl wearing a purple coat with matching gloves, hat, and shoes, reached out and pulled on my shirt sleeve. “Mr. K, I love trees so much. Without trees we wouldn’t have oxygen and I think they are so pretty.” I agreed with her and before I could try and delve into a lesson, yet another young boy shouted from the back of the line. “You know what we should do? We should each pick a tree, name it, and hug it.” My response was, “That is exactly what we should do.” Fanning out in front of me, 13 trees were given names and were embraced with loving arms. The scene was so beautiful I had to hold back tears. This gave me hope. Walking back towards the lodge, we stopped quickly in the prairie and hunkered down deep in the grass like field mice hiding from the wind. I gave them a quick lesson on prairies and their importance and rarity.

Before they got back on their bus that afternoon, I asked the children to each tell me something they had learned or loved while visiting Severson Dells. Many answers brought a smile to my face, but more than one answered that what they had learned was prairies are beautiful and rare. Then a little girl raised her hand and stated, “When I get home I’m going to have my Mom help me look up ways to help save prairies and protect nature.” This gave me hope.

Back on my deck at home, I watched the last time autumn color would bleed into the September trees and listened to the bulldozers and chainsaws roar and scream. They are cutting down the last of the old growth timber. They are taking the last lone soldier that just a month ago Ely threw his arms around to say good-bye. They are displacing countless creatures dependent upon cavities and structure found in old growth timber who are now homeless wanderers. Will they have time yet in the dwindling year to stock new dens with food? That is, assuming new living quarters can be found. Ten months to completely destroy what took centuries to create. The hope here in this moral monstrosity has to be that by empowering my pen to write and sharing the importance of nature preservation as a teacher, I can reach just a few, and those few reach a few more. The hope is in the change, the change of our attitude towards nature and most essentially the hope we never lose children who can create change.

‘I watched the last time autumn color would bleed into the September trees and listened to the bulldozers and chainsaws roar and scream. They are cutting down the last of the old growth timber. They are taking the last lone soldier. They are displacing countless creatures dependent upon cavities and structure found in old growth timber who are now homeless wanderers. Will they have time yet in the dwindling year to stock new dens with food? That is, assuming new living quarters can be found. Ten months to completely destroy what took centuries to create.’

I believe all children are born with a keen awareness of environment. The very first input of ambient information that we all experienced was a gasp of fresh air. We continue to grow and learn how to best survive in the environment of our communities, then we learn how to manipulate our environment to ease the burden of survival and, in turn, create our own islands of surplus. This is when we unfortunately become out of balance with our communities; as adults we lose awareness of the significance of that first breath. We as a community have no balance. We live in the same place but hardly know our neighbors. In some examples, which tend to be increasingly the norm, our “neighbors” live counties, states or even continents away. Scott Russell Sanders speaks of community in his book Hunting for Hope: A Father’s Journeys: “I wish to live in a community that has a keen awareness of its own history, one that values continuity as well as innovation and aspires to leave a wholesome place for others to enjoy, undiminished, far into the future.”

The disparity between our ancestral communities and today’s mostly digital communities bring me back to my conversation all those years ago with Uncle Mike. I wish for many reasons I could talk to my Uncle, let him know I’m still thinking about our conversation. I believe I could respond to him now with less of the unwise arrogance I had back then. I believe that unlike the clearing of land that occurred when we as settlers needed to clear land to feed ourselves and our communities, we now choose to clear land and develop land because we want to for any number of reasons: more tillable acreage, a subdivision of unnecessarily large houses, a new shopping center 10 miles from one exactly like it. And is more often the case, we simply stand by and bear witness to this nature-bullying without taking a stand.

I use the example of the forest ecosystem removal project here in Northern Illinois because I’m here to watch it every day, but land ethic is not an agriculture-exclusive issue. All of us reside on land, land that together we can make decisions to either protect or destroy. This story could just as easily be about fracking, commercial logging, fishing, mining, or any other use of land that has the potential to alter ecosystems. Those doing the most destruction have the most money. Why? Because we pay them to destroy. Greed has created unbalanced communities. Ed Abbey points out, “Original sin, the true original sin, is the blind destruction for the sake of greed of this natural paradise which lies all around us-if only we were worthy of it.” To destroy is easy. But to make the change in our behavior–to decide we have taken too much, to admit we are the problem, we killed the oceans, we killed the prairie, we are killing nature, we are destroying our habitat–is going to be difficult. But I believe a culture change can only start if individuals change their collective behaviors.

By changing our behavior, we change our communities. Let our communities influence other individuals so that truly holistic and sustainable behavior becomes the norm in our society. Hopefully before it is too late, we can reach a paradigm shift, an attitude adjustment, a wake-up call to how our decisions as consumers, producers, and landowners impact our species. The future of our species will not care how much money you or I have or how affluent we lived. They will care that there is clean air to breathe, clean water to drink, and wild places to find shelter from the stresses of life. They will need habitat. Will we leave them any?

It is November. Thoreau describes this month perfectly as, “the month of withered leaves and bare twigs and limbs.” The view from my deck will never be the same; the great horned owls’ bawl still echoes in my mind, the lone soldier that stood watching the first pioneer arrive, the countless migratory birds, the beauty of the woods are just a memory. It is time again as individuals to strive for a balance in ourselves, fight for balance in our remaining communities, learn from poor decisions, relinquish greed, live by the morals we would choose to pass along to our children, hold strong the importance of “harmony between men and land,” and cultivate again in our society the importance of a proper land ethic. This gives me hope.

About the author:

Greg Keilback is the Environmental Educator/Biologist at Winnebago County Forest Preserve District, where he leads educational programs at Severson Dells Nature Center and at other Forest Preserve District locations. He also oversees biological research and survey projects for the District. Prior to joining the Winnebago County Forest Preserve District, Keilback was Director of Land Stewardship at the Natural Land Institute of northern Illinois. His degree in Natural Resources Ecology and Conservation Biology from the University of Idaho-Moscow (2005), in addition to his experiences in restoration ecology, animal and plant biology, stream and riparian ecology and environmental interpretation made him the ideal leader to assist NLI in preserving, maintaining, restoring and managing natural land for the conservation organization.

While with NLI, Keilback implemented a hands-on educational Conservation Camp, a week-long training program that teaches young people about land conservation based on the Land Ethics of Aldo Leopold. Among his other achievements was successfully led stewardship volunteers in a three-year process to complete the oak savanna restoration plan at Nygren Wetland Preserve in Rockton, IL. He created the restoration management plan for the most recent land acquisition of Pecatonica Woodlands Preserve along the Pecatonica River. Keilback made numerous contributions over the years that helped protect and preserve the extraordinary natural areas of our community.