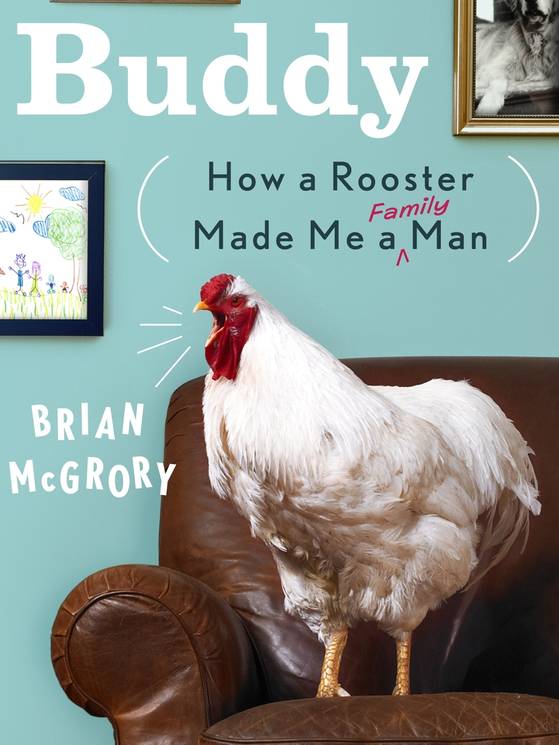

For his new book, award-winning veteran journalist Brian McGrory decided to write a shaggy dog story, except this shaggy dog story is chiefly about a rooster.

McGrory, who has worked for The Boston Globe for nearly a quarter century–as a reporter, editor, columnist and in December, he rose to the very top ranks, being named editor of the paper—recently penned a memoir of sorts, Buddy: How A Rooster Made Me A Family Man.

A major thrust of the book involves McGrory chronicling the process of forging a quintessential blended family—divorced, he fell in love with and married a divorced veterinarian, Dr. Pam Bendock, who had two young daughters—with the feathered wrinkle to this blended family being Buddy, the book’s titular rooster, who pretty well hated McGrory.

And constantly made that hatred clear in all kinds of ways, not least by frequently charging McGrory and trying to peck him in all parts of his body. And I do mean all parts of his body.

On more than a few occasions in Buddy, McGrory indicates the disdain is mutual, though in my reading of the book, not only do bird and man eventually achieve some sort of rapprochement, but I think they tip-toe past mutual admiration into—dare I say it?—love.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nQ25H9VrtBw

Video trailer for Brian McGrory’s Buddy: How a Rooster Made Me a Family Man

Actually, I did say it, early in the December 12 Talking Animals interview with McGrory, when I suggested his latest book (his fifth, after four novels) struck me as involving interlocking love stories: the first with his golden retriever and constant companion, Harry; the love story with the dog begets the love story with Pam Bendock, the veterinarian who cared for Harry. The love story with Pam begets the far more complicated love story with Buddy.

“Not sure I ever had the love story with Buddy,” McGrory answered, politely responding to what he clearly thought was a nutty contention. “I think Pam had the love story with Buddy. But that’s a little bit different. So, one of the last things Harry did for me, and he did many things for me [was showing me] you can really draw lessons from great animals.

“Throughout his life, Harry taught me to open up more, how to give, how to receive. I’ve always had this theory that you’re never more yourself than you are when you’re alone with a dog you really love, because you just let go, your true colors shine.”

We’ll come back later to my observation about his relationship with Buddy constituting one of the book’s love stories in a moment, as we did in the radio interview (spoiler alert: he ends up deciding I’m not completely out of my mind, after all), but we’d be remiss if we didn’t spend some time here on his unadulterated and profound affection for Harry. I suggested that the way McGrory writes about him made it obvious that he viewed Harry as a truly extraordinary dog, and one of the great loves of his life. This elicited less immediate pushback than my Buddy suggestion.

A vintage shot of Brian McGrory with Harry: ‘Throughout his life, Harry taught me to open up more, how to give, how to receive. I’ve always had this theory that you’re never more yourself than you are when you’re alone with a dog you really love, because you just let go, your true colors shine.’

“It’s odd to say it, but I think you’re exactly right,” he said. “Literally from the second I saw this creature –I went to Logan Airport to pick him up in cargo—and he might have been the most perfect physical creature I have ever seen in my life. To the point where all these burly cargo handlers were gathered around this dog, cooing at him, picking him up, petting him. And he was this frightened little puppy who had just come out of a crate after taking a flight up to Boston. And big a cliché as it is, it was love at first sight.”

The way this love affair played out is that Harry would accompany him everywhere he went, from the shops and restaurants and other beloved haunts in Boston, to the little vacation house McGrory bought in Maine, and beyond. This included tagging along even when McGrory was working, covering one story or another for The Globe.

And wasn’t pared back when McGrory was assigned to the White House beat during President Bill Clinton’s administration, or even when an internationally significant story was breaking. There’s an enchanting anecdote in the book along those very lines, amidst the very serious, dramatic announcement by President Clinton’s press secretary Mike McCurry that Clinton had ordered bombing runs against Afghanistan and Sudan–which McGrory paraphrased in the Talking Animals interview.

“I had trained Harry from the very youngest age to be off leash,” he recalled, “to be able to just follow me around, to heel, and to just be calm. To not step off a curb into a street. We lived in Boston together, in the city itself, and he was just trained where he would pad along beside me. And he would no sooner step off a curb until I stepped off the curb than he would jump off a cliff—he just wouldn’t do it.

“It was to the point where he would accompany me in stores, every time I got in the car, he would be there with me, he’d just be my shadow and it was really terrific. He was just a very, very special dog. I was covering the White House for The Globe, and I was out on Martha’s Vineyard covering one of [President] Clinton’s vacations—he took most of his summer vacations out at the Vineyard. This happened to be the year after the Monica Lewinsky revelations and I think he was sleeping in separate quarters in the Vineyard from Hillary and Chelsea,” he noted, chuckling at the President’s status in the doghouse, as it were.

Dr. Pam Bendock and Brian McGrory: Harry brought them together, Buddy…reserved judgment…

“It was kind of a do-nothing day and the White House press center was at a junior high school in the Vineyard. I was in the junior high cafeteria, just typing up a feature story. It was pretty languid, there was nothing going on. Harry was sound asleep at my feet. And suddenly in walks Mike McCurry. He had a special announcement to make. All the cameras gather around, there’s a dozen cameras or so.

“And Harry slowly wakes up, sees Mike McCurry—who he really liked—standing at the podium, picked up his tennis ball, and I’m sure he was thinking, ‘Thank God, someone’s finally going to play with me.’ He walked slowly up to the podium, drops the ball at McCurry’s feet. McCurry’s making this announcement about the bombing runs in Sudan and Afghanistan, looks at Harry, and kicks the ball toward him. Harry picks the ball up and drops it at McCurry’s feet again. And with the camera rolling—and I’m trying to get Harry; this is important!—McCurry looks down and says ‘Not now, Harry.’”

Laughing heartily at the memory, he added “I’ve always wondered will presidential researchers, years from now, be wondering when they listen to the tapes, ‘Who is this person Harry who had such an effect on foreign policy?’”

After several years of endless adventures together—not all of which had those levels of journalistic and national security implications—Harry, sadly, started facing the challenges that an older dog typically encounters, slowing down, becoming ill. In the book, McGrory can’t help but sound wistful describing Harry’s decline in the midst of yet another visit to Maine:

Walking off the beach that night, I knew Harry would never see it again. He had watched me packing a couple of hours before, so I suspect he knew it as well. Still, he came, reliably, readily, bravely. What mattered wasn’t so much where we were or what we were doing but the fact that we were together. Harry was calm until the end.

The dog died a month later.

In losing Harry, McGrory’s grief is palpable, and given the Harry that we get to know through McGrory’s skillful writing, it’s hard not to share that grief. But part of the reason it’s a tough loss for writer and reader alike is that Harry is a singular, even magical animal, and part of his magical impact is that, even as he was failing, he was in no small way responsible for spawning the romance that bloomed between McGrory and Harry’s vet.

“One of the last things he gave me,” McGrory explained, “is he introduced me to this wonderful veterinarian, who when Harry died, she and I struck up a relationship. And not too, too long after Harry died—a couple of years—she and I got engaged and eventually we did the whole thing: bought a house in the suburbs, we all moved in together.

Buddy in repose: ‘the most pampered rooster in the history of America’

“The different part of this for me was, number one, I moved to suburbia, which might as well have been Mars to me. Number two, she had two relatively young daughters, who were seven and nine at the time, who might as well have been Martians. I never had kids, I had no idea what they were like, I was terrified of them. And number three, she arrived with this pet rooster, who loved her—loved Pam—loved her kids, and absolutely hated me.

Of course, we’ve previously noted that Buddy hated McGrory, or at least that McGrory claimed that Buddy hated him. But as McGrory spins the yarn of his relationship with Buddy over the course of Buddy: How A Rooster Made Me A Family Man—which has elicited a henhouse full of rave reviews, with The New York Times saluting his “sure hand for polished storytelling”–it becomes increasingly apparent that the Buddy-McGrory dynamic was a good deal more nuanced than that.

If McGrory had been posting about this relationship on Facebook, I’m pretty sure he’d have to go with “It’s Complicated.” Indeed, at times, it seemed to boil down to a struggle to establish primacy as the household’s alpha male, and Buddy wasn’t about to countenance placing second in that race.

At the same time, part of the reason I had practically started my Talking Animals conversation by suggesting McGrory was engaged in a love story with Buddy was that their relationship observed many key tenets of a romantic comedy: the principals meet and immediately dislike each other, there’s bickering, and generally not getting along; then comes a pivotal moment of some kind where the pair achieve a breakthrough, if not a new, deeper understanding of each other. And then things proceed in a new, in-sync way. But maybe, I conceded to McGrory, I’m stretching here.

“No, you’re not with that, at all,” he said. “The thing about Buddy, it was pretty amazing to watch. Because I would see his relationship—he was the most pampered rooster in the history of America. He was given free run of our yard. Buddy was the product of an elementary school science fair in our hometown. One of Pam’s kids got an incubator and hatching kit to try to hatch chicken eggs for a science fair project. And sure enough, one egg hatched. In retrospect, thank God it was only one!

“And out comes this adorable little chick. Fuzzy, yellow, chirping. The chick is constantly handled, and petted, and caressed by the two daughters. The chick would sit on the couch watching television with them every night. The chick lived in a little cage on a console table in Pam’s living room. The chick outgrows the cage, moves into a dog crate on the living room floor and ultimately outgrows the dog crate. And Pam just puts him out in the yard, to give him free range of the yard.

“Every night he slept in the garage. And lo and behold, what they thought was a hen became a rooster. And we all move in together. And the rooster had his own rooster shed in our side yard, with transom windows, and still had a free run of the yard. Loved Pam, came inside and watched TV with the kids. They could pick him up, they could handle him. But he just didn’t understand why I was there. If he was overseeing this flock, what was this pathetic little creature doing?

Buddy dines with Harry’s successor: ‘As gentle as the lessons were that I learned from Harry, there were more tough love lessons I learned from Buddy,’ says Brian McGrory.

The pathetic little creature in this saga freely admits to hoping that Buddy would lose the battle for cock of the walk by default, assuming that living in the suburbs with a rooster, surely some of their neighbors would squawk about the crowing.

“First of all, I thought all the neighbors would complain,” McGrory confessed. “I was just waiting for that to happen. I thought the result of that was that Buddy would be carted off to a nice farm somewhere, where he would make a bunch of hens very happy. And instead of complaining, most of our immediate neighbors would show up at our fence with string cheese and cereal, and feed Buddy. We live on a relatively main road, yet cars would virtually come to a stop, drivers would beep their horns, kids would call out Buddy’s name—he became a tourist attraction, for God’s sakes.

“It never made any sense to me. But one morning, early one Sunday morning, a black SUV pulled up outside of our house. And the driver, who I couldn’t see, started shooting photographs of Buddy in the yard. Then, a week or two later, an animal control officer shows up at the house, and she does an inspection of Buddy’s rooster shed in the side yard.

“And I’m thinking ‘OK, this is great. Finally, we’re going to be told No roosters in the suburbs. It’s crazy.’ And instead, she tells Pam this is the single nicest rooster shed she’s ever seen in her life—she wishes she was Buddy!”

Brian McGrory: ‘It was really quite something to see that animal-human bond form with something other than a cat or a dog.’

Buddy didn’t cede much ground in this battle to be the household’s male major domo, though it did seem that eventually, each of the combatants came to respect, if not love, each other. It’s hard to assess just what Buddy learned from McGrory before he flew off to that great (and fancy) rooster shed in the sky. But looking back now, McGrory acknowledges that he’s a better man for knowing Buddy, that he saw and learned all sorts of meaningful things.

Marveling at the profound relationship that Buddy forged with Pam and the girls—I’m sorry to report that Buddy died (of an apparent heart attack), as I think McGrory was sad to report in the book, and genuinely sad to see—he said toward the end of the Talking Animals conversation, “It was really quite something to see that animal human bond form with something other than a cat or a dog. As time went on, I’m looking at this thing that so disliked me, growing more amazed at how he had it all figured out. He was so happy to be part of this pack, his flock.

“And he was so committed to everything within his little kingdom—within the fence line, within the house—that he worried not one whit about what was going on in the outside world. All he cared about was what he had, inside. As gentle as the lessons were that I learned from Harry, there were more tough love lessons I learned from Buddy.”

Click here to listen to Duncan Strauss’s Talking Animals interview with Brian McGrory.