(from left) Alison Balsom, Karl Jenkins and Kate Royal, photographed for the conductor-composer’s 2009 Christmas album, Stella Natalis: ‘The Peacemakers does seem an end to the sequence in a way; but in another way it could be looked at as a sequel to The Armed Man. The Armed Man ends with a plea for peace, and this continues it—it’s all a plea for peace, really.’ (Photo: Alison Balsom by Mat Hennek; Karl Jenkins by John Swannell; Kate Royal by Uli Weber)

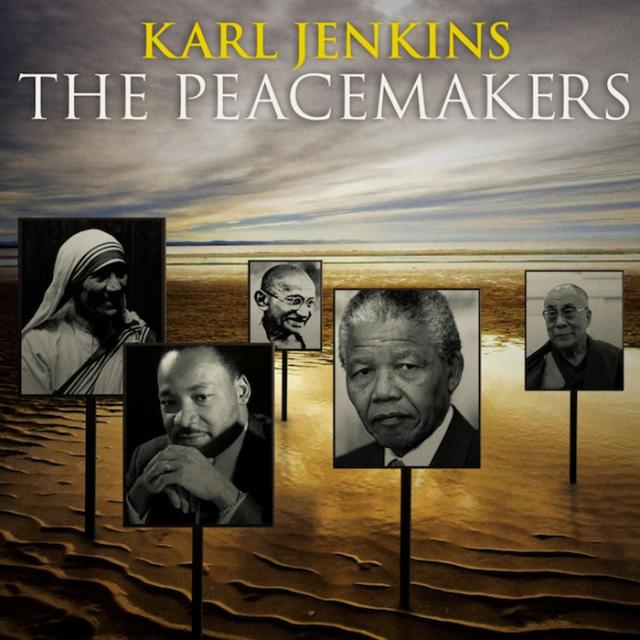

After emerging in the mid-‘70s as a key member of an influential progressive rock band, then spending the last half of the ‘80s and first part of the ‘90s writing award winning music for commercials, classically trained Welsh multi-instrumentalist Karl Jenkins began a new career as a composer and conductor. As such he won a devoted following–and equally rabid critics–for his hybrid works meshing symphonic elements with choral music and World Music appropriations of texts, vocals and instruments. In 2000 his The Armed Man: A Mass for Peace became a musical phenomenon and marked the start of a journey navigating the nexus of spiritual, inspirational and socially conscious themes advocating peace and non-violence. Last month he conducted the world premiere of his newest work, The Peacemakers, at Carnegie Hall. Centered on the words of iconic figures such as Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Gandhi, Nelson Mandela and Anne Frank, Jenkins’s latest grand pronouncement in this realm (it features a thousand-voice choir) is either journey’s end or a necessary sequel.

When Karl Jenkins stepped onto the Carnegie Hall podium on January 16, 2012, it seemed the culmination of a journey he began more than a decade ago, in 2000 to be exact, when at London’s Royal Albert Hall he conducted his The Armed Man: A Mass for Peace, a work inspired by the popular 16th Century “L’Homme armé” masses and dedicated to the victims of the Kosovo tragedy. A musical phenomenon, originally commissioned by the Royal Armouries Museum for the Millennium celebrations, the work has been performed more than one thousand times in 20 different countries, and its magnificent, inspirational “Benedictus” has leaped out of the Mass to become a world-beloved composition on its own.

‘Benedictus,’ from The Armed Man: A Mass for Peace. Composed by Karl Jenkins, with the London Philharmonic Orchestra and the National Youth Choir of Great Britain.

The years since the unveiling of The Armed Man: A Mass for Peace have seen Jenkins introduce Requiem (2004), a mass for the souls of the dead, with texts set in both Latin and Japanese on the theme of life’s cyclical nature of life, death and rebirth; Stabat Mater (2008), based on the 13th Century Roman Catholic prayer reflecting on the suffering of Mary, the mother of Jesus, at the time of the Crucifixion; Stella Natalis (2009), a largely sacred Christmas album of original songs for orchestra and chorus; and Gloria/Te Deum (2010), a choral work based on an early Christian hymn of praise still in use in Catholic, Anglican and Lutheran churches.

In typical Jenkins fashion, The Peacemakers arrives in the mold of the above-noted projects; that is, it blends symphonic and World Music elements with a large chorus (truly large–one thousand voices in the aptly named Really Big Chorus of London along with comparatively smaller choirs such as the Rundfunchor Berlin and the City of Birmingham Youth Chorus. Performed by the London Symphony Orchestra, the 17-movement work features guest artists Chloë Hanslip (violin), soprano Lucy Crowe, Davy Spillane on uilleann pipes, Indian bansuri player Ashwin Srinivasan, jazz saxophonist Nigel Hitchcock and bass player Laurence Cottle.

Karl Jenkins on The Peacemakers

In his liner notes accompanying The Peacemakers CD, Jenkins writes: “I have occasionally placed some text in a musical environment that helps identify its origin or culture: the bansuri (Indian flute) and tabla in the Gandhi; the shakuhachi (a Japanese flute associated with Zen Buddhism) and temple bells in that of the Dalai Lama; African percussion in the Mandela; and echoes of the blues of the deep American South (as well as a quote from Schumann’s Träumerei in my tribute to Martin Luther King. ‘Healing Light: a Celtic prayer’ is with uilleann pipes and bodhrán drums.” He dedicates the work “to the memory of all those who lost their lives during armed conflict and, in particular, innocent civilians.”

Beautiful, haunting, ethereal, searching, uplifting, earthy and majestic–Jenkins’s music is all this, even more so when the various choirs raise their collective voices in reverent conviction. In this instance they sing the words of Jesus (“Blessed are the peacemakers, for they will be called the children of God”), Mahatma Ghandi, Nelson Mandela, Martin Luther King, Jr., the Dalai Lama, Albert Schweitzer, Mother Teresa, St. Francis of Assisi, Sir Thomas Mallory, Percy Bysse Shelley (from “Elegy on the Death of John Keats”) and Anne Frank, along with passages from the Bible, Qu’ran and Bahá’u’lláh (founder of the Bahá’í Faith); one of the most moving numbers is “A Meditation: Peace is…,” humbly and tenderly rendered by soprano Lucy Crowe, singing text written by Terry Waite especially for The Peacemakers and imbued with his belief in peace as a healing, reconciling force. Waite is the former special envoy to the Bishop of Canterbury who, while on a mission to negotiate the release of four British hostages, was captured by Beirut terrorists on January 20, 1987 and held hostage for 1,763 days (the first four years in solitary confinement) before being released in 1991. Jenkins himself contributed exactly one line of his own–“No more war,” sung plaintively by the Youth Chorus at the start of “One Song”–and his wife and musical collaborator Carol Barratt crafted the stirring, idealistic lyrics for the heraldic album closer, “Anthem: Peace, triumphant peace” (“May all our paths meet up and lead to one holy place where peace shall reign in our hearts/one wondrous place when the world has peace, glorious peace, such peace.”), which includes, as sung softly by the Youth Chorus, this sentiment from Anne Frank: “How wonderful it is that no one need wait a single moment before starting to improve the world.”

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=77y7s7Ox_iY

Karl Jenkins, The Peacemakers, ‘I Offer You Peace,’ with the City of Birmingham Youth Chorus, London Symphony Orchestra and, on flutes, Gareth Davies.

The young Ms. Frank’s words might well describe the mission to which Karl Jenkins has dedicated himself since introducing The Armed Man: A Mass for Peace. He may be as much of a dreamer as John Lennon when it comes to promoting peace, but that has not deterred him from “starting to improve the world.” Jenkins’s detractors in the music press–and they are legion, generally torching his work as not being of sufficient intellectual or musical gravitas to be seriously judged classical compositions, and self-consciously manipulative in its co-opting of multicultural musical devices and texts that give his albums a broader, pop-based appeal than most classical artists could ever hope to achieve.

In a piece headlined “Karl Jenkins: meet Britain’s bestselling composer” published in the March 13, 2008 edition of The Telegraph, Adam Sweeting observed: Though he’s apparently mild-mannered and self-effacing, Jenkins’s work can provoke surprisingly bitter controversy. Another newspaper recently staged a debate in which he was denounced as propounding “a totalitarian mode of expression, feeding off a carefully cultivated cult of personality”; but he was also praised as “a great modern composer with a good old-fashioned tune inside him.”

Jenkins shrugs. “I think the classical establishment has changed, but you still get the kind of snobby, sniffy hardcore classical people who don’t look outside their box, especially at something that encroaches on it like I do. If I wrote a difficult atonal piece, it would be inherently acceptable even before I started writing it, unlike something that’s tuneful and that people will like.”

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BU8AOIbS_04

From the album This Land Is Ours (2009), ‘Cantilena.’ In his liner notes Karl Jenkins explains: ‘The idea came to me earlier in the year to record an album that reflected two important facets of traditional Welsh popular culture, the male voice choir and the brass band, brought together for the first time on a major record release. Male voice choirs and brass bands have been synonymous with our country since the industrial revolution and although this is true of many mining communities, particularly in the north of England, the male choir has a particular resonance in Wales. It was clear that I had to employ the best possible practitioners in these disciplines to make this project memorable and the choice of both band and choir was easy. It was crucial to have a choir that, while retaining the raw emotion of the traditional Welsh male choir, also possessed superb musicianship and reading ability, in the musical sense, which enabled me to explore more adventurous harmonies and sounds than is perhaps the norm within this genre, with the choral harmonies sometimes consisting of as many as eight separate parts when often two, or even one, is the norm.’

One of Jenkins’s early detractors was the prickly cultural commentator Norman Lebrecht, who once described the composer-conductor as “a newspaper composer,” meaning, as Lebrecht explained in 2010, “his music is ephemeral, hot today, late tomorrow.” After which Lebrecht added: “It looks like he’s proving me wrong,” a reference to a survey conducted by the British music publishing firm of Boosey & Hawkes, which represents literally hundreds of composers (including Karl Jenkins), seeking to ascertain which living composer could lay claim to his or her works being the most performed in the new millennium’s first decade. Stabat Mater came in at #10, with 57 performances; at #1, with 311 performances, was Jenkins’s 2004 Requiem. (Noting these results, Lebrecht couldn’t resist a parting shot at Jenkins, saying the poll confirms his suspicion of “a trend towards the simplistic satisfactions offered by the former ad-man Jenkins, as distinct from the more serious contemplations of post-modern genre leaders,” such as Steve Reich and John Adams. [Adams came in at #5 with his The Dharma at Big Sur [2003]; Reich apparently narrowly missed the Top 10 with his Cello Counterpoint.)

Well, Jenkins is indeed a former ad-man, a profession he toiled at from the mid-‘80s to the mid-‘90s, and at which he proved himself most accomplished, twice winning the D&AD award for best music to go with a Creative Circle Gold award and several Clio and Golden Lion awards. His themes were heard on commercials for the likes of Levi’s, Renault, Volvo, Pepsi, British Airways and, most famously, Delta Airlines and De Beers diamonds. The latter, in fact, propelled Jenkins back into the music business and begat his classical incarnation in 2008 when his album based on the De Beers music, Diamond Music, became a hit on the classical and pop charts both, thus establishing the crossover success that has endeared him to millions of listeners worldwide even as it has alienated many critics.

But to reduce him, as Lebrecht does, to “former ad-man” is unfair, a pejorative designed to allow snobs to dismiss Jenkins’s compositions out of hand and ignore the multitudes of listeners flocking to his concerts and eagerly awaiting every new CD. It also blissfully ignores and is a disservice to Jenkins’s history.

As part of his 60th birthday concert in 2004, held at Cardiff’s St. David’s Hall, Karl Jenkins conducts his Palladio, with Catrin Finch on electric harp. From Jenkins’s composer notes: ‘Palladio was inspired by the sixteenth-century Italian architect Andrea Palladio, whose work embodies the Renaissance celebration of harmony and order. Two of Palladio’s hallmarks are mathematical harmony and architectural elements borrowed from classical antiquity, a philosophy which I feel reflects my own approach to composition. The first movement I adapted and used for the ‘Shadows’ A Diamond is Forever television commercial for a worldwide campaign. The middle movement I have since rearranged for two female voices and string orchestra, as heard in Cantus Insolitus from my work Songs of Sanctuary.

Born February 17, 1944, and raised in the Gower village of Penclawdd, in the county of Swansea, south Wales, Jenkins was schooled in classical music from an early age, thanks to his father, an organist and choirmaster. Young Karl earned a position as an oboist in the National Youth Orchestra of Wales, went on to study music at Cardiff University, and from there matriculated to graduate work in London at the Royal Academy of Music and tutelage under the legendary Welsh classical composer Alun Hoddinott. (While at the Royal Academy of Music he also met and began courting Carol Barratt.)

After his Royal Academy experience, Jenkins gravitated to London’s jazz world, where he gained prominence playing baritone and soprano saxophone, keyboards and oboe while backing many of the city’s legendary names at top clubs such as Ronnie Scott’s. Following a stint as a member of Graham Collier’s band, Jenkins co-founded a pioneering jazz-rock group, Nucleus, which won first prize at the Montreux Jazz Festival in 1970. His prominence as a musician also landed him work playing oboe on Elton John’s acclaimed 1970 album Tumbleweed Connection and on Mike Oldfield’s 1973 classic, Tubular Bells (made legendary by the use of its music in The Exorcist). In 1972 he made a leap into the big time by joining progressive rock titans Soft Machine, leaders of the dynamic, barrier breaking “Canterbury Scene,” which included Caravan, Gong, National Health, Camel, Egg, The Wilde Flowers and others. In its original incarnation, Soft Machine had been managed by Jimi Hendrix’s management team and toured with Hendrix in the U.S. through 1968 (after which future Police guitarist Andy Summers joined the band). With his former Nucleus bassist Roy Babbington joining him in the ever-shifting Soft Machine lineup, Jenkins (with original member Mike Ratledge on organ and John Marshall on drums) was integral to the band’s move towards a more jazz fusion approach on its last three albums, one of which, 1975’s Bundles, found the band energized by the addition of the versatile Alan Holdsworth on guitar, an inventive player worshipped by Eddie Van Halen worship and once hailed by Frank Zappa as “one of the most interesting guys on guitar on the planet.” As musicians came and went, Jenkins remained part of a series of ad-hoc Soft Machine lineups through a final series of concert dates at Ronnie Scott’s in 1984. From there he gravitated to the advertising world.

From Adiemus V: Vocalise, ‘Mysterious Are Your Ways,’ the Adiemus Singers, Martin Taylor on guitar, and Karl Jenkins on piano and conducting the London Philharmonic Orchestra.

With the success of Diamond Music Jenkins was off into a new phase of his musical life, now as a classical composer and conductor. He began to assert an original vision immediately, with the 1995 release of the first of five vocalise-style albums under the rubric Adiemus. These harmonized vocal melodies with orchestral support contained no lyrics, but rather a language invented by Jenkins consisting of syllables forming words with no meaning save for the voices’ pitch and timbre, thus employing the voice purely as an instrument.

“The musical language of Adiemus,” notes Wikipedia, “draws heavily on classical and world music. Jenkins follows conventions of tonality up to a point—his harmony is derived from gospel and African music, decorated with functional dissonances such as suspensions and with greater freedom of movement between loosely related key areas. He avoids the most common time signatures, such as 2/4, 3/4 and 4/4, with a slow 3/2 being very characteristic along with 6/8, 9/8 and even 5/8 (Cantus Inaequalis from Songs of Sanctuary). ‘Free time’ is also prominent, in this as well as the majority of new age projects. The percussion section, when used prominently, typically gives the pieces an upbeat, tribal-like rhythm. The sound of Adiemus is generally identified with New Age or Celtic music; The Eternal Knot is an explicitly Celtic-themed album that formed the sound-track for the S4C [note: Channel 4 Wales] documentary The Celts.”

Apart from a live album (Adiemus Live, 2002) and two anthologies (Adiemus New Best & Live, 2002; The Essential Adiemus, 2003), the Adiemus project includes Adiemus: Songs of Sanctuary (1995); Adiemus II: Cantata Mundi (1997); Adiemus III: Dances of Time (1998); Adiemus IV: The Eternal Knot (2001); and Adiemus V: Vocalise (2003). The first three pop and classical chart topping volumes won 15 gold and platinum albums. Beyond his works for voice and orchestra, Jenkins’s resume includes secular music for choir and orchestra, concertos, works for string orchestra and a children’s opera (Eloise, based on the fairy tale “Wild Swans”). Not least in his catalogue: a 1996 album, Kiri Sings Karl, featuring the legendary Dame Kiri Te Kanawa performing Argentine and Welsh tunes Jenkins composed, accompanied in part by The Adiemus Singers, and accompanied by the Jenkins-conducted London Symphony Orchestra. He has been commissioned to compose works for the Royal Ballet, HRK the Prince of Wales and the London Symphony; his scores for the documentaries The Celts and Testament earned him British Academy of Film and Television (BAFTA) gongs, the unfortunately named British counterpart to the Academy Awards.

From Kiri Sings Karl (2006), Dame Kiri Te Kanawa performs ‘Antema Africana,’ arranger-producer-composer Karl Jenkins, conducting the London Symphony Orchestra, with Pamela Thorby on recorder.

This has all been prelude, though, to what has happened to Karl Jenkins since The Armed Man: A Mass for Peace was introduced. Though he has produced other works between then and now (notably the 2008 concertante Quirk: The Concertos), the five big works beginning with The Armed Man are stamped not only with Jenkins’s restless musical sensibility–always searching for new sounds in new combinations of voices and instruments across a broad spectrum of musical forms–but also with his conscience and sense of responsibility as someone whose own voice, as filtered through his original compositions, reaches literally millions. In The Peacemakers he has, as always, linked his music to a great spiritual tradition centuries old, and articulated a bracing moral vision of his dream of a newer, better world.

Speaking from his home in Wales, Jenkins discussed the making, meaning and intent of The Peacemakers, as well as how his present course has been shaped by the music and experiences of his earlier years.

We’ll get to the album soon enough, but I’d like to start by asking you about the roots of it, not musically but philosophically in your own experience. You have dedicated this this composition “to the memory of all those who lost their lives during armed conflict and, in particular, innocent civilians.” In looking through your biography I learned that your father was an organist and choirmaster, and began wondering if your pacifism is rooted in teachings of the church you attended in your youth, if it was born of philosophers you studied later in life and/or a general revulsion at the horrors of war you’ve seen in your lifetime? How do you account for it?

It’s kind of more universal than truly Christian. I think I’ve opened up my beliefs, if you like. I never saw the integrity of other faiths, from an early age, I suppose.

As far as this particular work goes, the genesis came initially from The Armed Man, A Mass for Peace that I wrote as a Millennium commission for 2000, commissioned by the Royal Armories, a body in the U.K. that runs the Tower of London and they a kind of military museum in Leeds as well. They wanted—just to touch on this because it is relevant when we’re talking about The Peacemakers—they wanted a work to commemorate the Millennium that told the story of war, the story of conflict—the battle itself and the aftermath. This particular work was dedicated to the victims of Kosovo, because the tragedy in the Balkans was unfolding at that time. And the text was a purely universal text—there’s a “Call to Prayers”; a poem by a Japanese poet who eventually died as a result of leukemia that developed as a result of the Hiroshima bomb; there’s Hindu text, there’s Biblical text, there’s a lots of poetry. So there was a universal message. The kind of philosophy, or the reason I was writing it—well, I was writing it because I was asked, but apart from that, it made a big impression on me as I was writing it, and it made a big impact. The piece has been done globally I think ten thousand times now within the last ten years.

Since then it’s always been on my mind to extend that idea. Since then I’ve written a requiem; Stabat Mater, to do with Mary and the cross; but in all my work, although even setting standard Latin text I always bring in other cultures—like in the Requiem Japanese haiku poetry; in Stabat Mater text taken from the ancient world, all of that geographical area, the Holy Land, if you like, but bringing in different cultures—Muslim culture and religion and others as well. So I was slowly coming around to my idea of writing a piece on iconic peacemakers. On a non-philosophical level and a practical level if you like, I have a series of albums over a period that I’ve been asked to write and also commissions from outside. So part of it is that I’ve been asked to do certain things.

The Peacemakers came along at a suitable time, really. The idea was that I would use text from iconic peacemakers as the basis for the work and use their words to inspire some music of my own. And that’s how it happened. When I started writing it was a bit fragmented; the text wasn’t all collated at the same time because we didn’t have clearances all at once from all these people, or their estates. But eventually it all came through. So it wasn’t written chronologically in the sense that the work is presented now, but that doesn’t impact upon it at all. So that’s how it came about. The whole idea developed, and we decided to have a children’s choir and all sorts of musical considerations came into it: what instrumentation to use; how best to make it effective; different elements of musical composition became part of the process.

- Anne Frank: ‘How wonderful it is that no one need wait a single moment before starting to improve the world.’

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OZ78iDfXIt4

From Karl Jenkins’s The Peacemakers, ‘Healing Light–A Celtic Prayer’

These ‘messengers of peace,’ as you call them, whose words are sung by the choirs, all spoke and wrote extensively on the subject of peace and non-violence. Out of all their written works and public statements, how did you pinpoint the exact passages that best illustrated your aims in The Peacemakers?

It’s a question of research then, I suppose. One looks at each figure. It’s amazing how many quotes we found when we went to the estates that were attributed to these figures but they weren’t authorized as being from these people at all. There was one of Gandhi that the Gandhi estate said he didn’t say; there were a couple of Albert Schweitzer quotes that the estate said he did not say. But I sifted through enough of them and found some very pithy, iconic words. Some are just a sentence—Anne Frank, “How wonderful it is that nobody need wait a single moment before starting to improve the world.” Some are much longer; some occupy whole movements, some occupy, as I said, a mere fragment. So what I was left with, and what I ultimately used, was amazing. I take no credit for that, because these are the words spoken by iconic people. So it was a bit of research, a bit of choice. I had some new text written; Carol Barratt, a musician/composer—she’s also my wife—but she’s a composer and wrote some words for me. And also Terry Waite wrote some iconic text, some marvelous words from the modern perspective, as it were—a peacemaker who’s still with us. He’s a friend, an official friend, of the project, and a personal friend as well.

That’s how it came about. Through a process of trial and error, getting some themes together, making them fit, certain words, it all fell into place like some giant jigsaw.

How did you forge a friendship with Terry Waite? Did you know him before this project?

I did, but not from a long time ago. Fairly recently, in fact. He came to a performance of The Armed Man, A Mass For Peace at an international music festival that he was president of, in north Wales. We met through that. He was impressed by the work, not that that’s relevant in any way, except that it generated this acquaintance and we keep in touch. He was only too pleased when I asked him to become a friend of this project.

Terry Waite: ‘Peace is the fragile meeting of two souls in harmony. Peace is an embrace that protects and heals. Peace is a reconciling of opposites. Peace is rooted in love, it lies in the heart waiting to be nourished., blossom, and flourish, until it embraces the world. May we know the harmony of peace. May we sing the harmony of peace. Until in the last days we rest in peace.’ From ‘Meditation: Peace is…’ written for The Peacemakers.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iY6td0zb600

Terry Waite’s ‘Peace Is’ as set to music by Karl Jenkins on The Peacemakers. Karl Jenkins conducting at the Royal Festival Hall.

You mentioned the albums you had done prior to The Peacemakers, starting with The Armed Man, A Mass for Peace. There’s also the Gloria/Te Deum project in that group. These are characterized by the diversity of musical and cultural resources you’ve availed yourself of. You’ve used texts sung in English, Latin, French, Hebrew, Greek, Japanese and Aramaic and your native Welsh language, or spoken in Sanskrit and Arabic; you’ve composed Palestrina-style polyphonic songs, quoted from Rigoletto, and included, on Gloria/Te Deum, a serene pop song, ‘I’ll Sing Music,’ sung by Hayley Westenra who has a bright, ringing soprano that would be right at home on the Broadway stage. You compose for orchestras and large choirs, but your arrangements also include instruments indigenous to the areas from whence some of the music emanates, as you do on The Peacemakers in using the bansuri and tabla in the Ghandi section and the temple bells for the Dalai Lama’s section, and there are numerous examples of this on the other albums. The point is, the way you’ve reflected the multiculturalism of our time in the context of these spiritually oriented works reflects the need of many people nowadays to find a spiritual home that is less dogmatic and more humanistic than what the established order can offer. Would that be true of you as well? Is that what these works are telling us about you?

That’s exactly true. It is. I was raised a Christian and I still hold certain Christian beliefs, and I suppose technically I still am a Christian. But as I said, I recognize and appreciate the existence of other faiths. If there is a supreme being somewhere or some spiritual force looking after us, it’s the same one for all mankind; not that the Christians in the west have one of their own and the others count for nothing. I think by breaking down such barriers the world can become more universal and hopefully a more peaceful environment for all mankind.

With Karl Jenkins at the piano, Hayley Westenra sings ‘I’ll Make Music,’ from the album Gloria/Te Deum (2010)

Given your history of quoting diverse cultural resources, musical and literary, and almost every album having a distinct message, it seems in the The Peacemakers you’ve distilled your approach to its essential components in order to emphasize the message–there are no spoken parts in foreign languages, the texts from what you call the “messengers of peace” are set to music and sung in English by the Berlin choir and the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra Youth Chorus. Some critics have complained that, for instance, in Gloria/Te Deum the readings in Sanskrit and Arabic disrupt the mood and may undermine the point of the album for English speaking listeners. No such claim can be made of The Peacemakers. You can follow the lyrics in the liner book and there’s no ambiguity or puzzlement as to what’s being said. This is really focused on reaching its audience on a fundamental, accessible level, and you’re making less demands of the audience than you have in some time in order to get the point across.

Right, but I didn’t start off with such a clear-minded view of it all; it was a question of what worked best as each quote came up. It was more like I started writing it and realized after about thirty minutes of music that it was all in English. (laughs) I never thought about language being a barrier anyway, because it’s always translated in the booklet. You know, one gets performances in English of previous classical works in German, or whatever. I don’t think historically the language really impacts the music; I don’t think that’s the case. Although Italian opera sounds better in Italian than in English. But it seemed a good idea to continue with it in English; it does make it simpler, I agree, and it’s more immediate, the words are heard as they’re sung and not translated in a booklet. It makes it more cohesive. Also I suppose most of the world speaks English nowadays anyway, so it was an obvious thing to do. As I was researching the quotes, because I speak English and little else, I was working in English from the earliest stage—I wasn’t researching text in other languages. There is one exception though—one movement is the word “peace” in seven languages, some ancient, some modern.

It seems, from the outside, that you were consciously pointing towards The Peacemakers as the ultimate destination in a journey that began with The Armed Man. Was there some point in the process of creating The Armed Man that you began to envision it as part of a larger body of work addressing the issues of peace and spirituality, and began incubating ideas for the subsequent projects?

No, not really. I came to The Armed Man and that genre, really, fairly late in life. It was mid-‘50s I guess. I was classically trained, so that’s always been a part of my culture. Having been a musical tourist for many years, I came—it was my first what one might call—although I hate categorization—it was probably my first work that was called a “classical” piece, that label. I came to that from the Adiemus project, which was kind of semi-classical, but really more—it was classical but it drew from other cultures in various ways. More so than the work since.

So The Armed Man was the first. Thereafter I had this drive to set classic texts that had been set by composers in the past—great composers, far greater than me. It was an ambition, if you like. There’s a raft of them out there, and there were a number of kind of obvious ones I got around to. There was Requiem , and then Stabat Mater, Gloria/Te Deum. Iconic text, Latin texts, that have been set for generations by composers. But, as is my wont, to look outside the strictly western European both in texts and in terms of instrumentation. I drew from other cultures, such as the Japanse haiku in the text of Requiem; Middle Eastern text in Stabat Mater; Te Deum is more normal, in that it is only Latin.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oqlRa0IXhjc

‘Cantus Lacrimosus,’ from Stabat Mater (2008). Karl Jenkins conducting the Royal Liverpool Orchestra & Choir, with Belinda Sykes (soprano and duduk) and Jurgita Adamonyte (soprano)

It was an exploration of these different things, and maybe to see them in a new light. Not a new light in terms of the way most contemporary composers see something new, which is making it harmonically different, or harmonically ambitious, or harmonically innovative, because I think every avenue has been explored now with regards to atonality or tonality. But I wanted to bring a freshness to these projects by visiting other cultures, or bringing other cultures into what I do, as I said both in terms of text and in terms of instrumentation, particularly percussion instrumentation and using indigenous and native instruments from around the world. So that was part of the plan and part of what I’ve always done.

When I did The Armed Man I had no idea what I was going to do next, and then this drive, this idea, occurred to me. Requiem was the first step, but when I was doing that I didn’t think what would be next. It was a question of when one was done I’d move on and consider what I wanted to do. And there were other commissions and work, solely instrumental, that came into the equation as well. I wrote a marimba concerto [Note: La Folia: Concerto for Marimba and Strings, 2008] and a concertante, Quirk , for the London Symphony Orchestra (released, 2008) and a couple of odd things that surfaced that weren’t part of this choral vein.

Then I came to The Peacemakers, and as you say it does seem an end to the sequence in a way; but in another way it could be looked at as a sequel to The Armed Man. The Armed Man ends with a plea for peace, and this continues it—it’s all a plea for peace, really.

Adiemus: Songs of Sanctuary, from the first of five Adiemus albums (1995). Karl Jenkins, conductor.

In your liner notes you cite the line from Rumi–“All religions, all singing one song: Peace be with you”—as being so critical to this album’s concept. Why is that so?

This has to do with Bahá’u’lláh, founder of the Bahá’í Faith, in that I quote from the doctrine that the world is all one people and we’re all here together. We share the same sky, the same earth, the same seas, and we are one people. And that’s what I mean by all religions singing “Peace.” An obvious statement (laughs)—if there were peace there’d be no conflict, no war. It’s a simple, obvious, almost stupid thing to say. But it’s a truism. That’s what we’re aiming for, really, Whether it will ever happen, I doubt it, human nature apparently being what it is. We’ll see. (laughs) I won’t see it; I won’t be here. But someone will see it further down the line.

I’m sure there are more than a few great stories emanating from the experience of the musicians participating in this project. One story in particular you mention in your liner notes concerns the presence of the Rundfunkchor Berlin choir, and in its membership one woman in particular, Judith Engel, who had a moving story to relate to your wife and collaborator, Carol Barratt. Why is the choir’s presence on the recording so relevant to your aims in this work?

The Rundfunkchor Berlin Choir was born in the East, and after the second World War found itself in the western sector. Judith Engel, as she grew up, was an East German girl and she had to have permission–she was allowed to come through but she had to return every night, which she would because all her family were there. And just one day she realized, just before she joined the choir, she made this journey and just one day the wall was normal and it had an enormous effect, obviously–her world was transformed, she was free essentially, the world was a different place. Then she joined the Rundfunkchor Berlin, which by that time was in the West. They’re a fantastic choir and they all sing English impeccably; I defy anyone to say it’s not an English speaking choir, but some of the older ones, their second language is Russian, and the younger ones, their second language is English, of course, which could reflect on their early upbringing and the way they were so many years ago.

From The Armed Man: A Mass for Peace, ‘Agnus Dei,’ by Karl Jenkins.

There’s an interesting story in your liner notes about the difficulty of recording the Really Large Chorus. You had to do it in stages, apparently.

Well, we couldn’t get a large enough space for them to all come in under one roof at one time, so we used the iconic and famous Abbey Road Studios, made famous by the Beatles. But it was actually opened in the 1930s by Edward Elgar, the great English composer, who opened it with a recording with the London Symphony Orchestra. I think it was 1931, and everyone’s been there since. I recorded there in a different life with a band I was in called Soft Machine. The Beatles, Pink Floyd and loads of Hollywood movie scores in there. It’s a famous building in St. John’s Wood in Abbey Road, and it’s a huge studio, the biggest in London but even it couldn’t take what we needed. It could take about two hundred at a time, two hundred singers, and we had a thousand. Just two movements in the work, implementing the Rundfunkchor Berlin, a different sound, an amateur sound, but still contributing some energy and size, not least. So we had them rehearsing in a school down the road, and then we had two hundred at a time shuttled in (laughs), on a conveyor belt, and eventually we got the magic thousand–I don’t know why it’s magic, it’s just a number, a thousand singers on these two tracks, a PR kind of thing. But it worked, and it is quite a massive sound.

All my recordings are layered anyway, so that wasn’t a new process. You start with a layer, whatever it is, percussions, strings, whatever, and you build it up to a computerized metronome that takes into account speed-ups, slowdowns. I was going to say it’s not metronomic but it is metronomic in a sense; it’s sourced from a metronome but it’s not what that implies, which is rigid, with no fluidity. It’s still constructed to play to a performance. It works quite well and it worked l in this instance. Then I spent a few days editing and cutting it into shape.

So you enjoy that recording process?

I enjoy the process, yes. I don’t like editing; it’s boring, frankly. I mean I’m there, but I rely on engineers to do that chore.

How long did The Peacemakers take from beginning to end, once you started recording?

The recording process was fairly concise. The long period is the actual composing, which took about nine months, and once that was ready to go, it was fast. There might be weeks in between, but the orchestra is in a day or two. Rundfunkchor was done in two days in Berlin; the CBSO youth choir was done in a day and a half in London; and the big chorus of a thousand was done in a day. From beginning to end the recording was maybe five or six weeks, but as I say, within the parameters of the six weeks it took about five days, I suppose

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_aNnItpn6HY

Karl Jenkins, conducting in the studio and discussing the recording of his Christmas album, Stella Natalis (2009). With the European classical singing group Tenebrae and acclaimed trumpet virtuoso Alison Balsom, plus the Adiemus Singers.

Are you a disciplined writer, one who devotes a certain amount of time each day to the task at hand, no matter how you’re feeling?

Yes, pretty much. I write every day. I get up fairly early when I have a project, and I write every day. I don’t have much truck with the idea, many people idyllically want composers to be like that, waiting for the muse to strike or wandering through the fields waiting for the fears to come. But in my case it doesn’t come like that; it’s a question of doing some work, and then ideas come. Some are rubbish and some are possible, and you retain the possible ones, develop them and you end up with a piece of music. Then you hone it and trim it to one’s own satisfaction. That’s what’s good about deadlines—you’re forced to deliver. Many composers work in isolation, without commission, and even some that work on commission can never finish it. They can’t let go. I think that’s a lesson I learned when I was writing as a media composer for many years—if you don’t deliver you don’t get the work, and you don’t get paid, and you don’t live. The great composers of the past—Bach, Mozart, whoever—they wrote to commission, Bach for his church, Mozart for his patron. In that sense their job was being composers, which I admire. There’s no kind of fanciful notion as to what they do—they have to get on with it and deliver by a certain date.

What do you want listeners to get out of The Peacemakers?

Inspiration, I suppose, some sense of spirituality. My first job, as I see it, is to move people emotionally. There are two functions: one is the purely musical function of wanting people to love the music, or enjoy the music, get something out of it spiritually, really—something that enriches them, if you like. Then there’s the other, philosophical angle, which is consider where we are in the world, consider what is happening to the world, and with these iconic figures through generations the message holds true: we’re still striving for a peaceful world. That’s the other side of the coin. There’s a musical side and the other side.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4Q1sm0bVDVc

The magnificent ‘Anthem: Peace, Triumphant Peace’ from Karl Jenkins’s The Peacemakers, with The Really Big Chorus (1000 Voices), Rundfunkchor Berlin, London Symphony Orchestra (LSO), Chloë Hanslip, Simon Halsey, Gareth Davies, City of Birmingham Symphony Youth Chorus.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IUsFxmaIClw

From Karl Jenkins’s The Peacemakers, ‘He Had a Dream (Elegy for Dr. Martin Luther King).’ With the Rundfunkchor Berlin, London Symphony Orchestra (LSO), Karl Jenkins, Nigel Hitchcock, Chloë Hanslip, Simon Halsey, Gareth Davies, Laurence Cottle, City of Birmingham Symphony Youth Chorus.

People of our generation likely first heard of you in Soft Machine. There surely were some on these shores who knew of Nucleus, but Soft Machine had more of a name in America. Of your experience in that world, what would you point to as the lasting lessons that have been useful to you as a classical composer and conductor?

I wouldn’t think there are any kind of musical lessons. I’ll explain why I went into that world of Soft Machine. I had a fairly classical upbringing and training from my father as a boy. Then studying music at the university [Cardiff University] and then at the Royal Academy of Music in London. So I was thoroughly trained in and aware of all the classical tradition and classical culture, musically. The issue of composition came up when I was a teenager, when I was hired to do it academically, then going on into university. There was no scope at that time to know composition, really. And writing atonal music, or dissonant music, didn’t attract me, frankly, although I liked a lot of music from the second half of the 20th Century. Early Schoenberg, not much of the second Viennese school, Webern not so much. That was a time when it all changed. After that I did lots of theaters where classical music went into chants, and the John Cage thing, but it didn’t appeal to me as a medium of expression. But jazz always did. Jazz always was and still is essentially tonal music. Many people find it a bit cacophonous, I suppose, but to me it always was accessible and tonal. And also very exciting because of the rhythmic element and the improvisation element. So I was hugely attracted to jazz, which resulted in me becoming a jazz musician when I left Royal Academy. I worked as a jazz musician around London, in various bands, and then graduated into Nucleus and then Soft Machine, which by the time I joined was essentially a band that incorporated lots of different facets in its music making. It was by that time a jazz-rock fusion band in that it encompassed jazz solos with rock rhythms as opposed to jazz rhythms. But it was a bit wider than that. It was a lot of what we called “pattern” music then; we started using Echoplexes, like repeat boxes, and it became what today is called minimalism. This was the same time as Terry Riley’s “In C” became a fashionable piece and was fairly influential globally. Then in the States Miles Davis was crossing over to jazz-rock fusion, so we were all part of that era.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jjecEnj8Ot8

Soft Machine, live at Montreux Jazz Festival, July 4, 1974, performing ‘Hazard Profile.’ Karl Jenkins on keyboard and oboe. Mike Ratledge, keyboards; Allan Holdsworth, guitar; John Marshall, drums; Roy Babbington, bass.

I suppose what was different about that life as opposed to my life now, the main difference, of course, is that I’m now my own boss. I do what drives me and what I want to do. Soft Machine was a cooperative band, and that can become difficult for many reasons. Arguments can arise through material—“why are you writing more material than I am?” Just internal strife, which is why so many bands break up. And of course being on the road with a pretty small group of people—at our biggest we were six, maybe, and after a few it was four. Lots of good memories, of course, fun, travel and lots of good music. It was a time when you see the world, meet different people. In all those ways it was a good experience. The bad experiences grew over a period, inevitably, because when you’re in this goldfish bowl with the same people on tour, things become fractious. But I still know the ones that are alive–a few of them have passed over, unfortunately—and I’m on good terms with them

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KnyKYDy6O8Y

Soft Machine, live at Montreux Jazz Festival, July 4, 1974, perform ‘Lefty/Penny Hitch.’ Same lineup as above.

In terms of music development, what it did do—and after that I went into media music—was implanted in me, which I always had, actually, was that I always tried resist categorization in music. All these different influences came out of Soft Machine, the jazz-rock, the minimalist thing, the patterns, and then later as a media composer I wrote advertisement spots for a long time with some iconic directors, people who went into movies, such as Ridley Scott, Tony Parker, Tony Scott, people like this were advertising directors in London then. If one landed a film with one of those people, one knew the production values would be very high. The films look good and they were rewarding experiences. During that process I learned a lot about Third World music and ethnic music. And all these influences went into the melting pot and came out in what I later did. Which is essentially a classically based composer who draws from different cultures and different experiences and tries to bring them into the music that a composer—maybe me—writes. I’m trying to make the influences an intrinsic part of what I do so that it sounds as though it comes from one place, and not bolted on by artificial means. It’s important to me that it doesn’t sound cobbled together.

What other projects are on the drawing board right now?

I’m working on a piece called “Songs of the Earth.” It’s commissioned by the BBC National Orchestra of Wales and is tied into the 2012 Olympic Games in London. There’s a cultural Olympiad going on alongside the more well known Olympiad. I’ve gone back to ancient Greece and used as names of the movements the names of figures from Greek mythology. the Titans; Chaos, which is the beginning of the earth as the Greeks perceived it; Gaia, mother Earth. So these are the titles of the movements. For the actual text of the piece I’ve gone back to the Adiemus project and used my own mythological language, which ties in nicely with the Greek mythology. It’s the invented language of Adiemus, a bit like scat singing in jazz in that it’s an invented, organized series of phonetics. So that’s that, and it will be performed in March. A bit like Carmina Burana in flavor; not the same but in that kind of direction.

From Quirk: The Concertos (2008), ‘La Folia,’ concerto for marimba and strings, with Neil Percy (marimba) and the London Symphony Orchestra conducted by Karl Jenkins.

Will that entail a large choir as well?

I think it’s going to turn out to be about three hundred. So it will be big. But that’s purely because of the situation. It’s the BBC National Orchestra of Wales and Chorus, but they’re also inviting some of the youth choirs around Wales, of which there are many, Wales being a land of song—singing is very important to Welsh people and there’s a strong choral tradition here. I have no doubt the choirs will be excellent, and when they come together it will be about three hundred.

Well, it’s not a thousand-voice choir, but that’s pretty good.

(laughs) No, not the thousand voices, but it will be big enough.

Why have you been drawn to these large choral works?

The size is fairly accidental. Peacemakers can be sung with two small ensembles. But if you’re asking about big choral works, it’s fairly often the circumstances. The reason we had a thousand on Peacemakers, that was only two movements and I wanted to bring them in for a bit of earthiness, a bit of massive size. But in sixty, seventy minutes’ worth of music, they occupy like five, and the Rundfunkchor Berlin fifty, I think, although they sound bigger because they’re a sonorous group and they’re all pro singers. The Children’s Choir was thirty, I think. My Requiem choir wasn’t big; Stabat Mater choir wasn’t big. So they’re not always large choirs. The reason why I use choirs is because I think I have more of a style or a voice in my work in that area. My instrumental music, when it’s solely instrumental, tends to be quite quirky. It’s a different face of the coin really. But my heart is in the choral sound, in using voices.