On The Absence, Melody Gardot, trading on mystery and control, is vibrantly present and just out of reach. That’s the point.

From her solo debut in 2008 (Worrisome Heart, produced by Glenn Barratt) to her 2009 Grammy nominated dazzler, My One and Only Thrill (produced by Larry Klein) to 2012’s The Absence (which hasn’t been nominated for any big awards but is this publication’s Album of the Year—hey, hey!), New Jersey-born, Philadelphia-residing (maybe) Melody Gardot has succeeded in insuring we know less and less about her even as we seem to know more, or think we know more. On the one hand, she seems like every other woman who’s been scorned in love but resolves to love again until it’s right; on the other, she seems as complex as the icons with whom she shares the headline above—outwardly glamorous, someone who incites strong feelings in her audience but who is always at a distance from us. Otherworldly and worldly; always dressed to the nines in an era when the female superstars of pop are wearing bikini underwear or less onstage, or posting self-shot nude photos of themselves online; possessed of sexual allure that draws men and women alike to her, although she has never been linked to any romantic partner and will admit only to always sleeping with…a guitar (“It doesn’t matter who’s in the bed with me, by the way–the guitar is always there,” she told The Telegraph’s Craig McLean in the most revealing of the few interviews she’s granted, published in The Telegraph of May 29, 2012).

Like Dietrich, like Deneuve, like Garbo, Ms. Gardot trades on mystery and control wrapped in the classiest of exteriors. In an appraisal of Dietrich published in The Hairpin of May 23, 2012, Anne Helen Peterson made an observation of her subject’s appeal that might well apply to Melody Gardot in reference to her “ability to simultaneously embody the passive and the dominating, the masculine and the feminine, the demure and the suggestive. While other Hollywood stars worked to make themselves seem ‘Just Like Us,’ Dietrich was never like us.”

‘Wicked Ride,’ from Melody Gardot’s first recording, Some Lessons (aka The Bedroom Sessions, an EP released in 2005), recorded her hospital bed while rehabbing from near-fatal injuries suffered when she was hit by a Jeep while riding her bicycle on the streets of Philadelphia.

From a very young age, even before some of the things that are considered to be landmark events in my life happened, I’d always felt like an old soul. I felt like I needed to do everything, as if I was going to die at 21. So I was moving through things too quickly, without as much care as might have been necessary. I had aspirations to work in fashion, I had aspirations to work in design, to work in arts, graphics media. I didn’t know patience, I didn’t know the beauty of taking your time. –Melody Gardot, from the fascinating 2010 documentary The Accidental Musician,

If anyone thinks Melody Gardot is “just like us,” The Absence should put those notions to rest once and for all. This is not coming out of the blue, this persona. If you’ve heard not only the three Verve albums mentioned above (Worrisome Heart was initially an independent release before Verve picked it up and signed the artist along with it) but the ultra-rare 2005 EP Some Lessons (also known as The Bedroom Sessions, because its seven songs were recorded in the artist’s hospital room as she recovered from near-fatal injuries suffered after being hit by a Jeep while bicycling on the streets of Philadelphia), you know Melody Gardot has never been a simple, easily accessible character. The first words we hear on Some Lessons, in the song “Wicked Ride,” are the halting “There comes a time/in ever-y little girl’s life/when her momma says, ‘girl, do your best, ‘cause one day you may come to find/that all of your life has been a wicked ride…” Worrisome Heart, in retrospect, seems like an effort to prove momma wrong. Ms. Gardot’s voice is lighter and more perky than the sultry, earthy instrument we know now, and though its title track, the album’s first cut, is a saloon blues in which she declares at the outset, “I need a hand with my worrisome heart,” the album’s dominant mood is upbeat, and its bright pop-jazz milieu houses generally hopeful ruminations and reflections on the state of the heart (“Love Me Like a River Does” and “All That I Need Is Love” being two standout performances). It was one and done for that approach: 2009’s My One and Only Thrill is replete with romantic ambivalence and the certainty of her life being “a wicked ride” but with more ambitious and richly textured arrangements (several with Latin underpinnings at their core, a telling watermark) and the most persistently smoldering vocals any artist had put on disc in some time. But as Tom Waits observed, “The large print giveth, the small print taketh away.” So it is that the bubbly, infectious joy bursting through the uptempo love song “If the Stars Were Mine” gives way immediately to the swaggering told-you-so of “Who Will Comfort Me” and then to the velvet hammer she wields on a faithless lover in “Your Heart Is As Black As The Night.” For every action—that is, for every buoyant emotion (“Our Love is Easy,” one of the more humorous titles in the Gardot oeuvre)—there is an equal and opposite reaction that mandates, for example, Harold Arlen & Yip Harburg’s “Over the Rainbow” (the only cover song on any Gardot album, save for a version of Bill Withers’s “Ain’t No Sunshine” included in the Deluxe Edition of My One and Only Thrill) be offered practically as a dirge in which bluebirds may as well be buzzards. Yet, immediately preceding “Over the Rainbow,” the artist’s last self-penned words on the album come in a soft, introspective pop ballad, “Deep Within the Corners of My Mind,” and articulate a hope for nurturing a deep and burning love, one not without complications but worth fighting for nonetheless. With warm strings rising softly under her vocal, Ms. Gardot whispers: What you do to me is like a page right out of Hemingway/Though I try to fight/All the words you write/Leave me standing in the starring role in some tragic lover’s play/But deep within the corners of my mind/I’m praying secretly/That eventually in time/There’ll be a place for you and me. It cannot be an accident that the sentiments and the hymn-like melody echo West Side Story’s “Somewhere.”

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=am_A5PvEnJE

Melody Gardot, a live version of ‘Deep Within the Corners of My Mind,’ a song from her Grammy nominated album, My One and Only Thrill. This performance was captured at Umbria Jazz, Teatro Morlacchi, Perugia, Italy, July 10, 2010.

Come The Absence (released in May 2012) the starry-eyed romantic of “Deep Within the Corners of My Mind” has vanished, the Latin influence reigns supreme and the lyrical focus is centered more on self-affirmation, or on remembrances of places more so than people, or on existential questions having only rhetorical answers. The album’s final cut, “Iemanja,” begins as a frisky samba and has good sport with her presence in South Africa (“White lady gone to the Southern sea/Why do you appear so suddenly/We want to honor your vanity/With little bitty boats set out on the sea”) before winding down to a quiet, gospel-inflected benediction, with Ms. Gardot accompanied by a house wrecking group of largely female backup singers whose propulsive, lively sound recalls he all-male Ladysmith Black Mambazo’s indelible contributions to Paul Simon’s Graceland; the rhythm slowly resumes a sprinting pace and the whole stew of voices, percussion, woodwinds and stringed instruments congeals into a celebratory finale at the four-minute mark. Now, if you’re eyeing the song list in the liner booklet, you’ll see “Iemanja” listed as clocking in at four minutes, exactly where the above-mentioned flourish subsides. But on iTunes, you’ll see it as having a running time of 18 minutes, 13 seconds (18:13). For 14 minutes and 13 seconds, at the very close of her album, Melody Gardot vanishes into thin air, as the only sounds heard during this time, beginning at 15:15 are those of ringing bells; voices chattering away indistinctly in what sounds like a restaurant setting with plates and silverware rattling; at 15:35 all this disappears; in its place emerges a mélange of thumping drums, abrupt alto sax eruptions, Middle Eastern guitar licks, a male voice apparently crying out for help—a sound collage, in other words—which in turn recedes, giving way to those ringing bells again, at which point we hear a car starting and driving away hastily.

Melody Gardot, ‘Iemanja,’ from The Absence. This is the abridged 4:01 version, minus 14 minutes-plus of silence and a three-minute sound collage.

Although some may think this merely a display of artistic vanity, or overreach, in the context of Melody Gardot albums this vanishing act has meaning: Just when you think you know her, she winds up a deeper mystery than ever. In going off the deep end as she does in “Iemanja,” Ms. Gardot has made it impossible to guess where she might wind up next, except to say that the sound collage sounds almost like a conscious attempt to undermine the beauty that has unfolded over the course of The Absence, with the person most responsible for it being absent herself in the end.

The backstory of The Absence is that after she had finished working My One and Only Thrill, Ms. Gardot left her Philadelphia home and began traveling throughout South American and Europe, not by design but rather on instinct: As she told McLean, “I just packed my bag and went one day. I wound up travelling kind of haphazardly by the seat of my pants, booking a ticket the day before, sometimes changing it. I was trying to find something about these cultures, the basis of which was I felt that no matter what country you’re in, or what language you’re singing in, you wind up united through the sounds.”

(In fact, she has allowed the lease on her Philly apartment to expire. This revelation prompted The Telegraph’s McLean to wonder if she is in fact technically homeless now. “Homeless has such a negative connotation,” she responded in perfect Dietrichian disdain. “Life is simple. But the way that I work is so intense that having a home is only purposeful when I have the time to be there. My requirements and my desires are relatively small–things like having a bed, a shower. A bathtub is usually high on the list–I love bubble baths.”)

‘…the way that I work is so intense that having a home is only purposeful when I have the time to be there. My requirements and my desires are relatively small–things like having a bed, a shower. A bathtub is usually high on the list–I love bubble baths.’

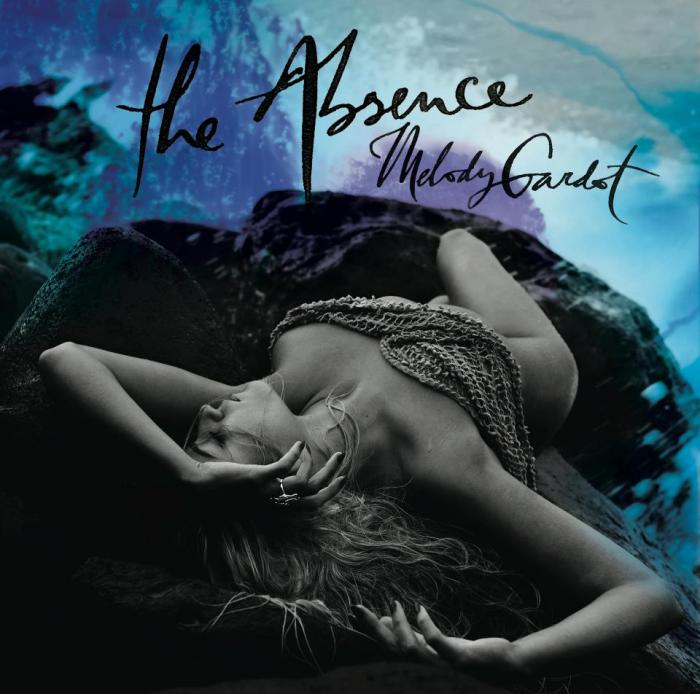

McLean rightly praises The Absence as “a bold new direction.” Working with Brazilian composer Heitor Pereira and recording in Brazil, Morocco, Hawaii and Portugal, the music of The Absence fuses flamenco, samba and fado styles with the classic pop-jazz that is the artist’s forte (consistent with the multinational aspect of the project, Ms. Gardot sings in three languages on the disc). One supposes that the boldness of this project extends to the album cover and liner photos depicting the nearly nude artist in various states of repose on a beach, with only minimal but strategically placed netting covering key portions of her anatomy.

The triumph of The Absence is not only in the demonstrated artistic growth of an exceptional artist who is only beginning to tap the depths of her gift, but indeed in its very existence, along with all her other records. Anyone who has read anything about Melody Gardot knows of the horrific accident (mentioned earlier) that shattered her pelvis, damaged her spine at its top and its base, inflicted near-fatal head injuries and left her suffering from aphasia (speech loss). When that Jeep ploughed into her bicycle and permanently altered her life, she was 19, a fashion student at the Community College of Philadelphia who played local hotels and bars, singing tunes by Billy Joel, the Mamas and Papas and Duke Ellington (or “Radiohead to really old jazz,” as she once said). She began classical piano lessons at the age of nine but two years later, she told McLean, switched over to blues and jazz because “I was adding new notes to the music, because I was hearing new things and decided to color outside the lines.”

Melody Gardot, ‘Mira,’ the first track on The Absence

Her injuries confined her to bed for 11 months and necessitated her re-learning everything most of us take for granted, such as walking, speaking, brushing teeth and all the other basics. During her rehab she took up yoga (and became a Buddhist), and worked with occupational and aqua therapists. The ever-present stylish cane she sports has become a fashion trademark for her, but it has practical application: she needs it to walk steady. The stylish dark glasses she’s never seen without protect her eyes, now light-sensitive as the result of the neural damage she suffered. She’s taken up a macrobiotic diet and undergoes daily treatments for her various ailments, and, according to the McLean interview, is careful about where she goes and where she stays, being acutely sensitive now to both cold and barometric pressure.

If all this weren’t enough of a burden for a wandering troubadour, Ms. Gardot admits pain is her constant companion. She used to travel with a TENS (transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation) machine, which uses an electric current to stimulate the nerves for therapeutic purposes. When the TENS broke she turned to other methods of pain management, none of them pharmaceutical. “I don’t believe it’s good to be dependent on one thing,” she told McLean. “In very severe moments, ultrasound, TENS unit, shiatsu, acupressure, acupuncture, myofascial release, craniosacral, osteopathic manipulations–any of these works very well. And I can use them in a balanced way to pull myself back into shape momentarily.”

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vpbSIORJNr8

Melody Gardot hosts The Absence album preview

This is all part of a recovery process that Ms. Gardot told Interview magazine took longer than usual because “the damage that was done to my body was gradually diagnosed, instead of immediately. It took nearly two years for me to say that I could successfully walk. It was scary. And in a way, when you’re faced with something like that, it forces you to change, and very quickly. I think that unconsciously, I felt called to a challenge–a challenge to regain something. I knew I couldn’t regain everything and I had to surrender to that, but once I did, my simple goal was–this is going to sound really funny–but, my simple goal was just to get into high heels.

“When someone tells you you’re not going to walk again and you spend about a year and half on your back, your clothes don’t mean much. I was in a robe every day, so I gave everything away—my whole wardrobe, down to the last dress. But at some point I woke up, maybe about four or five months after having done that, and I thought, You know what? I really want to try to wear high heels. That’s why I wanted to learn to walk. It sounded really stupid but I just wanted to see. That to me was sort of definitive to who I was. So that was my goal. I would do some of my physical therapy in heels.”

Ms. Gardot’s resolve to rise above her infirmities—including learning to walk in heels again (is that not perfect?)—is a natural outgrowth of a hardscrabble life. The only child of a single mother, a photographer who struggled to make ends meet, she never knew her father and apparently never speaks of him (hence the ambivalence towards men as expressed in her songs?). This upbringing—“I know my mom worked three jobs to pay $300-a-month rent. I know we shared cans of food for dinner–one can, for a grown woman and a little girl. I know we slept in the same bed for a long time, because there weren’t two. I know that that woman put herself on the line so that I would be OK.”–along with the care she received while recovering, has inspired her to launch a music therapy program at the University hospital where she was treated; an outgrowth of her travels abroad in making The Absence is a music school she’s helping build in Rio de Janeiro’s shantytowns.

Melody Gardot, ‘Goodbye,’ from The Absence

But were it not for The Accident, the Melody Gardot we celebrate here may never have surfaced. Without discounting all the medical expertise that went into her rehabilitation regimen, a doctor’s suggestion that she immerse herself in music made all the difference in her recovery, and in her life.

“Well, musical therapy was something of a revelation,” she told Interview. “I was abandoning medicine and adhering to the concept of Eastern medicine, and with that I needed something to help my state of mind, because I was a really stressed out. It was a lot of pain, and a doctor said to me at one point, ‘You know, the most important thing is to find something that makes you happy.’ That’s where it started. He said, ‘What did you used to do before the accident?’ My mom was there, and she said, ‘She used to play piano at piano bars,’ and his eyes just lit up. He was like, ‘You have to do music.’ At that time, I was devastated because he sent me home to play piano and I couldn’t even sit. So I learned to play guitar on my back while I was bed-ridden instead. I only thought to record the songs because sometimes I would I couldn’t remember what I had just done. Eventually I started singing, because I thought if I sang it that would help to remember even more. But I wasn’t trying to sing. And then one day–this is really weird–I just wrote a song. It came out at a rapid rate and I recorded it and I listened back to it and was like ‘Wow, it’s a tune.’”

Five other tunes followed “at a rapid rate” as well, and those became The Bedroom Sessions, a disc that found its way to Helen Leicht, a local DJ who cued it up on the air and began receiving a flood of requests for more Melody Gardot songs. “She loved the music,” she said of Ms. Leicht in a 2009 Blues and Soul.com interview, “really embraced me, encouraged me a lot, and insisted I press more CDs. Which was around the same time I met Glenn Barratt, who offered me the opportunity to record properly. Though, of course, at first I didn’t feel I was ready. I thought all this happening was ridiculous for somebody who’d just started playing guitar because she was trying to improve her memory! You know, suddenly here they were asking me to make a full-length CD–and I was like, ‘Are you crazy?’ But then eventually I called them back a couple of months later, and that’s when we made [Worrisome Heart]. Then, after around five months went by, some record company people started coming to see me performing, and eventually started asking if I’d sign with them.

On Later…with Jools Holland, May 8, 2012, Melody Gardot performs ‘Amalia,’ from her album The Absence

In her Bedroom Sessions liner notes, Ms. Gardot explains the recordings thusly: Microphone stands adjacent to hospital bed, 8-track beside ice packs and analgesic balms. The album was recorded while recovering from an auto accident where Melody (19) was hit while riding her bicycle home in Philadelphia, PA.

Why is this relevant? Well, most of the songs wouldn’t have happened had she not been hit in the first place. “Some Lessons” wouldn’t exist. That song in particular is a quiet reflection of the scene that flashed through her mind following the impact. The song was written while she was still unable to walk. “Somewhere between my many medicine cocktails and the time it took for them to set in.”

Yet the story of “Some Lessons” is far less tragic than it seems. Intimately recorded bedside—the bedroom sessions are a detailed portrait of one girl; one bed; one guitar; one piano; one sound.

Melody Gardot: The Accidental Musician, part 1 of a three-part interview filmed in 2010, directed by George Scott

Melody Gardot: The Accidental Musician, part 2

Melody Gardot: The Accidental Musician, part 3

Suddenly, with The Bedroom Sessions, Melody Gardot had fallen into a career. Since then, her trajectory has been strictly upward: with Worrisome Heart came the Verve deal, then the Grammy nomination for My One and Only Thrill, and along with all this a rigorous touring schedule that has her in Europe most of the year, where she draws large crowds across the continent, with only a smattering of dates in the U.S., where she is, inexplicably, less well established.

Maybe The Absence, with its panoramic view of what’s on her mind, will make her more of a Stateside phenomenon. If nothing else, it establishes her as songwriter capable of effectively probing and reflecting on more than the yin-yang of romantic interludes, even as it demonstrates how compelling a temptress she can be.

The cheery, gently swinging drive and percolating bass lines of “Amalia” carry Ms. Gardot’s wispy, fluttering vocal in a song seemingly addressed to a child (“Well when you wake in the morning/little eyes open wide…” and later, “Maybe you’re learning to fly…”) but equally about the singer taking charge of her own life (that line about “Maybe you’re learning to fly” is followed by a terse “So am I”), asking rhetorical questions of herself (“Where do you go when worry takes you? Where do you go when somebody makes you cry?”), then answering them, to wit: “Finding a way out on the open road/going whichever way the wind gon’ go/taking your chances on the open sea/such a funny little bird and you’re now with me.” The melancholy inherent in the narrative is true to the fado tradition in Portuguese song, but Ms. Gardot and Mr. Pereira are about working new variations on time-honored traditions here, which are honored structurally (and in titling the song after the most famous of all fado singers, Amália Rodrigues) although the lyrics disdain fado’s saudade for a more optimistic outlook.

Melody Gardot and Heitor Pereira, ‘Se Voce Me Ama,’ from The Absence

Pealing church bells introduce “Lisboa,” a curiously ambivalent love song to Lisbon (“the sorrow of your days gone by/now the hinterland of lovers should lay/beneath all your vacant skies…” and later, “A paradise beside the sea/there’s a beauty/to the absence of painting all your scenery”—not the only reference on the album to things or people being absent in telling ways, hence, one assumes, the album title), one of the key cities Ms. Gardot spent time in during the world travels that informed The Absence. Her vocal is as shimmering and cool as the samba rhythm it floats over, but the reverie is suddenly disturbed, at the 4:12 mark, by a distant female voice shouting “All of you! Sing it with me! Okay?” Similarly, at the beginning of “Goodbye,” a husky, male smoker’s voice lets out a malevolent laugh, then disappears when the song rolls out deliberately in a sinister Brecht-Weill mode, with hints of Dixieland here (emphasized in a lengthy, keening clarinet solo) and of smoke-filled cabarets there, before winding down as some disembodied voice speaks indecipherably deep in the mix. Inviting the listener in and then figuratively pulling the rug out of from under him is an infrequent occurrence here, but not so infrequent that you aren’t conscious of the artist never wanting you to get too comfortable in her presence. Waits: “The large print giveth, the small print taketh away.”

Melody Gardot, ‘Lisboa,’ from The Absence

But of course, given her album dedication, in part, to “my exes and my lovers,” you can expect the old ambivalence to surface, and so it does. In “If I Tell You I Love You,” we get: “There are so many things I could do, my love, to convince you my love is divine/there are so many words I could tell you/there are so many moments I’ve pined/but I say if before we go to the land down below you/if I tell you I love you, I’m lying”; and we get, “there are so many secrets to tell you/there are so many men on the line”; and we get, “If you like your women sweet/consider me your wine” against an atmospheric backdrop fashioned by banjo, clarinet, an eerie haunted house organ, a gypsy violin (even a whispered “Je T’aime” at the end) in what constitutes a ramshackle, Waits-ian ambience. A sumptuous but delicate Brazilian ballad, “Se Voce Me Ama” (“The Voice Loves Me”), is tender and subtly heated in its duet passages with Heitor Pereira, whose singing voice bears a truly uncanny resemblance to Antonio Carlos Jobim’s soothing, laid-back timbre; the Billie Holiday vulnerability and ache in the trembling affections she articulates over a soft wash of Riddle-esque strings in the über-romantic “My Heart Won’t Have It Any Other Way,” clocking in at a tidy 2:35 and assuming the position of the album’s most concise and most seductive discourse on terms of endearment, is the closest this album gets to the touching sensitivity of “Deep Within the Corners of My Mind.”

As aloof and mysterious as Dietrich, Deneuve and Garbo, Ms. Gardot differs from this iconic trio in one important aspect: all three were mentored by domineering men (Dietrich-Josef von Sternberg; Denueve—Luis Bunuel; Garbo-Mauritz Stiller), whereas she is her own creation, still evolving, still in pursuit of her greater purpose and ultimate identity but always the captain of her ship. Since she leaves us no clue at the end of The Absence as to her next port of call, we can only assume her restless quest will continue, and it will continue in the face of the pain she lives with every day. Undaunted, she is.

A live version of ‘So We Meet Again My Heartache,’ from The Absence

“Music is everything,” she told The Independent’s Elisa Bray in a 2009 interview. “It’s the reason why I have joy now, but, more importantly, it’s the reason why I am who I am. It’s given me purpose and it’s taken me around the world. In a way I feel that music is the man who walked along and swept me off my feet and now we are on a journey together. I don’t know how long it will last; if it’s anything like my other relationships I better start talking fast…it could be over soon.

“But it’s beautiful.”

Postscript:

Reviews of The Absence upon its release in late May were almost uniformly positive, with a critic here or there grousing that too many of the songs sound the same, or generally that the album lacked much variety. But even those who had complaints wound up admitting it rose above its minor flaws to be, ultimately, something special from a unique artist.

One of those who had a complaint was an Amazon customer reviewer who identified himself only as Amazon Chuck. Though he awarded The Absence five out of five stars, he wondered, as per the headline on his review, “What’s with the popping on Track 3, ‘So Long’?”

Writes Chuck: I would expect this distracting popping/cracking if it was an uncared for vinyl album, but this is throughout the song as an obvious defect, not in tempo with any of the music. You can even hear it with the sample clip playing.

That’s garbage to release an album with such a cheap sounding artifact. Otherwise I have enjoyed the past two albums from Melody.

OK, I am adding an update…and I am sure others will have the same concern because it is not in tempo with the music, only on the one track, and no mention of it in the product liner. I had my box outside in the mailbox to return the CD for refund, when after emailing Melody Gardot at her website (in case she did not know about it), and she was gracious enough to reply. As a result, I have changed my rating from 2 stars to 5 stars, and grabbed the return box to Amazon before the Postman arrived. Here was her gracious response, that I am only posting so others having the same concern will have a way to take this into account.

Yes, irate Chuck wrote to Ms. Gardot and she figuratively removed the thorn from the lion’s paw, in a quintessentially Melody way:

Hello Charles! I’m sorry you find this a defect but this is in fact not an error!

The sound you hear is a small click from the nails–as it has the sound of an old vinyl.

If you could picture the sound, it’s a small musician sitting beside the group, contributing to the song with only his hands, a smile, and the click of his finger nails. Some of the greatest musicians I have ever met have lived on the streets and while being very poor, make sounds with their mouths, their hands, essentially only what they have before them: their bodies. In this way it is an homage to the absence of any instrument beyond the human body. This is also a focus on the nature of microtones (the tiniest sounds!).

I hope the image your mind can create can reharness the beauty you have in your mind while listening to the album.

Kind regards,

xx

Mme