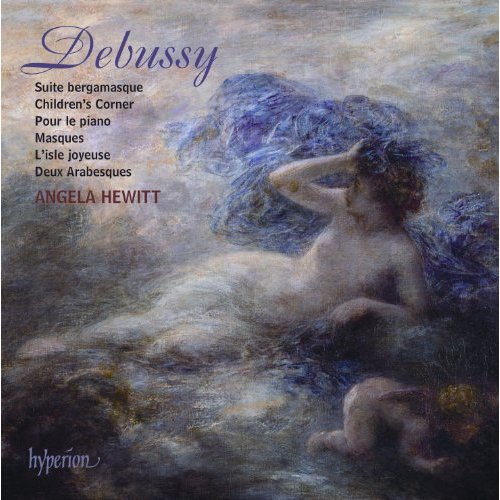

Debussy: Solo Piano Music

Angela Hewitt

Hyperion

Angela Hewitt on Debussy: His Life, His Music, Her Album

Angela Hewitt

(Ed. note: Scholarly, informed and insightful, Angela Hewitt’s liner notes for her new album of Debussy’s solo piano music are among the finest we have encountered in recent years. Given the emotional power of this album, having Ms. Hewitt’s own thoughts on her approach to the 19 selections she chose is an invaluable enhancement to the overall experience of immersing yourself in the subtlety and ethereality of Debussy’s music. Various critical perspectives on Ms. Hewitt’s album are offered following her notes.)

Claude-Achille Debussy was born above a china shop owned by his father. The date was 22 August 1862; the place was Saint-Germain-en-Laye—some twenty kilometres from Paris. There were no musicians in the family. His father Manuel had been in the military, and married a seamstress, Victorine Manoury. There was an uncle who moved to Manchester in 1872 and who taught music, but Debussy never met him or his three English cousins. As a boy he was called Claude. During his adolescence he switched to Achille, even going as far as signing his name Achille de Bussy. When he was thirty he reverted to Claude, and stuck with it.

His childhood was troubled and Debussy himself never spoke of it, while admitting that he hadn’t forgotten anything. When Claude was five the family moved to Paris, where his father became a travelling salesman. After the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War in 1870 Manuel joined the National Guard. When the Commune was defeated he was sentenced to four years in prison, but only served one—an incident that was covered up in Debussy’s lifetime. His mother didn’t care much for bringing up children, and left the job mostly to her husband’s sister, Clémentine. Claude in fact never went to school—something he never quite overcame. His spelling remained faulty until the end.

Angela Hewitt, ‘Clair de lune’ by Debussy, live at the Royal Conservatory of Music at Toronto’s Koerner Hall

The family moved house four times in five years, and they were always broke. Manuel Debussy (‘the old vagabond’, as his son later called him) did occasionally take his son to hear the operettas of Offenbach (which Debussy loved all his life) but decided that Claude was to be a sailor. In 1870 a pregnant Victorine took her children to Cannes where they stayed with Clémentine and her friend, the banker Achille-Antoine Arosa. It was there that Debussy received his first piano lessons, paid for by Arosa, with a certain Jean Cerutti (who seems to have been more of a violinist than a pianist). They returned to Paris the following year, in 1871, and took a small apartment in the Rue Pigalle. Manuel, while in a prison camp, made the acquaintance of Charles de Sivry, whose mother, Antoinette Mauté, was a piano teacher from whom Debussy took lessons. Although her claim to be a student of Chopin was probably far-fetched, Debussy’s did acquire his love for Chopin’s music from her. More importantly, perhaps, she was the mother-in-law of the poet Paul Verlaine, who wrote La bonne chanson for her daughter, Mathilde. She looked after her young pupil with great affection—something which Debussy later in life remembered with gratitude.

It was after only a few months of her tuition, at the age of eleven, that the gifted boy took the entrance exam at the Paris Conservatoire, and passed. His classmates later recalled that when he turned up for it he was wearing a sailor’s cap with a tassel. Debussy spent the next eleven years trying to be himself within an institution that didn’t want him to be anything of the sort. He started off by intending to prove himself as a pianist, but this didn’t work out as planned, much to the chagrin of his parents. He probably had a very personal idea of how the classical repertoire should be played. We know that Ambroise Thomas, the Director, very much disliked his interpretation of the F minor Prelude from Book II of Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier, saying that he had the presumptuousness to consider it a piece of music rather than just a simple exercise. His teacher, Marmontel, appreciated his gifts and predicted a great future for the boy who had ‘a true temperament of an artist’. He won certificates for playing Chopin’s Piano Concerto No 2 before he was twelve, and for one of the Ballades a year later. But despite his attempts, he never received a Premier Prix in piano. Perhaps his aversion to competitions accounted for his lack of success.

In the harmony class of Émile Durand, which he entered when he was fifteen, things were not much better. When Debussy refused to follow the rules, Durand would purposely keep his homework for the end of the class and then ravage it with corrections. There’s a story that once, when the teacher was getting ready to leave the room, Debussy went to the piano and brought forth cascades of his favourite chords, much to the delight of the students. Durand slammed the lid on his fingers. Twenty-five years later Debussy, who by then had revolutionized the language of music, admitted that he “didn’t do much in harmony class.”

Claude-Achille Debussy

He did finally get a Premier Prix in piano accompaniment and this allowed him to enter the composition class of Ernest Guiraud when he was eighteen. However, two other events from that same year were important to his formation. The first was an invitation from Nadezhda von Meck, the Russian businesswoman most famous for her friendship with and patronage of Tchaikovsky, to spend the summer with her family as piano teacher and accompanist. This he did three years in a row, forming a great attachment to them (and almost marrying one of the daughters). Madame von Meck called him ‘my little pianist’ and nicknamed him Bussyk, sending one of his compositions to Tchaikovsky for his opinion. (He found it very nice but lacking in unity.) Debussy travelled all over Europe with them, and of course stayed in Moscow where he became familiar with the Russian School. All of this opened his eyes to the wider world.

The second event was his meeting with the amateur singer Blanche-Adélaïde Vasnier—a married woman thirteen years his senior. She attended a singing class where Debussy was the accompanist—a job he had taken on to earn some money. He soon became a daily visitor to the Vasnier household where a room and piano were put at his disposal, living there more than with his parents. And of course he fell desperately in love. His first important compositions were the songs he dedicated to Madame Vasnier and with which he made his debut as a composer.

Debussy got along well with his composition professor, who socialized with his students outside of class, even playing billiards with them. In 1883 he competed for the famous Prix de Rome but was unsuccessful. He tried again the following year, and while waiting for the results on a bridge overlooking the Seine, a friend tapped him on the shoulder and said: “You got the prize!.” Debussy writes that at this moment “… my heart sank! I saw clearly the irritations and worries the smallest official position brings in its wake.” As Jean Barraqué wrote in his excellent biography of the composer: “Every hindrance, every obligation was not only intolerable to him but undermined his vital forces. His pauses, his lazing around, his dreams—all were an integral part of his creativity. He wanted to decide at each instant what to do with his life.”

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VXcyk5q6zfU

Debussy’s ‘Serenade for the doll,’ one of the selections on Angela Hewitt’s new album of the composer’s solo piano works. (This version is performed by pianist Francois-Joel Thiollier.)

His years at the Villa Médicis in Rome, where the winners of the prize were sent, were for him a drag. He hated the place. He managed to escape several times (once meeting Mme Vanier in Dieppe without her husband’s knowledge) and finally left before the three years were up. Back in Paris, he was given a cold reception by the Vasniers (remarkably the husband had stayed a close friend and confidant throughout the affair with his wife), no doubt partly due to their disapproval of his leaving Rome. The subsequent “période bohème” saw him frequenting cafés, travelling to Bayreuth to hear the operas of Wagner (paid for by a friend), hearing Javanese gamelan music at the Exposition Universelle in 1889, and frequenting the literary milieu—especially that of the symbolist poets. He didn’t get too involved with musical establishments. When asked to be a witness at a friend’s wedding, he wrote his profession in the register as “gardener.”

Compositions now started to be published. It is interesting to see that, although a pianist, the greatest advances in his early works were in the field of song (as seen in his beautiful Ariettes oubliées, for instance, to poems by Verlaine). They are much more advanced than his piano pieces of the same period. The latter include the Deux Arabesques, Danse, and the Suite bergamasque—all recorded here.

This recording starts with the suite Children’s Corner, published in 1908. After living with two women (one his wife, and both of whom tried to commit suicide when the relationships failed), and many affairs, Debussy met the mother of one of his pupils who was to become his second wife. In Emma Bardac he for the first time had a partner who was intellectually stimulating. Three years before they married, their daughter, Claude-Emma, was born. Debussy probably loved Chouchou (as they called her) more than anyone in his life. It was fortunate for him that he didn’t live to witness her death of diphtheria at the age of thirteen.

The English titles are original. Debussy was a great anglophile (although he spoke little English) and Chouchou’s governess was an Englishwoman, Miss Gibbs. The third piece of the suite, Serenade for the Doll, did have its title first in French (Sérénade à la Poupée) and was written two years before the rest—when Chouchou was only four months old.

Contrary to what some might suppose, this is not music that Debussy wrote for his daughter to play immediately, despite his dedication on the score: “To my beloved Chouchou, with the tender excuses of her father for that which follows.” She did learn to play the piano later on, and Marguerite Long remembers hearing her play the fifth piece of this suite, just as her father did. When she was very young, she told Madame Long: “I don’t know what to do. Daddy wants me to play the piano … But he forbids me to make a noise.

Debussy, ‘Doctor Gradus ad Parnassum,’ one of the selections on Angela Hewitt’s of the composer’s piano music. This version is performed by Stephen Malinowski.

This is not, however, childish music, even if it can be managed by youngsters. The initial Doctor Gradus ad Parnassum is much more than a warm-up, even if Debussy is thumbing his nose at poor old Clementi and his boring studies. When the tempo marking was missing from the first proof, Debussy wrote to his publisher: “Doctor Gradus ad Parnassum is a sort of hygienic and progressive gymnastic exercise; it should therefore be played every morning, before breakfast, beginning at modéré and working up to animé.” I think he was being just a trifle sarcastic. There is a lot of beautiful music in this piece, and to play it as an exercise would not do it justice.

Chouchou’s stuffed elephant is portrayed in Jimbo’s Lullaby, where the composer writes the description ‘un peu gauche’ (a little clumsy). One can imagine a scenario in which the elephant at first refuses to go to sleep; then, in the middle section (where the new theme echoes the lullaby ‘Dodo, l’enfant do’) he has a story told to him; and then when the music returns to the initial tempo and major mode (and with the two themes combined), he finally nods off. There is great tenderness and humour in this piece—qualities that pervade the entire suite.

The Serenade for the Doll is a remarkable piece, combining simplicity with sophisticated means of expression. To the strumming of a guitar accompaniment (‘delicate and graceful’) the doll dances for us, while the serenader sings and sighs. The piece has those wonderful sudden changes of mood so typical of children. Debussy asks for the soft pedal to be used throughout—even when marked forte.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y1YHnYX8xfM

Debussy, ‘The snow is dancing,’ one of the selections on Angela Hewitt’s new album of the composer’s piano music. This version if performed by pianist Francois-Joel Thiollier.

The next piece, The snow is dancing, depicts the bleakness of a snowy day and the sombre mood it provokes—waiting for the sun to return. It’s interesting that Debussy uses a four-note ascending motif as an ostinato that is also found in Le tombeau des naïades (from Chansons de Bilitis), written some ten years earlier, in which ice and snow form the backdrop. This is the hardest piece of the set in every sense. It takes great control of touch and sound, especially to get that “blank” effect. Debussy was very meticulous in differentiating between pp and ppp, and this should be observed. He also insisted that interpreters of his music should imagine the piano as an instrument without hammers, striking the key in such a way so that the vibrations of the other notes would be heard “quivering distantly in the air.” When Debussy made rare appearances abroad playing pianos that he wasn’t familiar with, there were often complaints that he couldn’t be heard. This was, for sure, a new way of playing the instrument!

The Little Shepherd, of which Chochou also had a toy, is a pastoral poem in music, in which the melancholic shepherd improvises on his flute. Twice he becomes slightly more jovial and breaks into a dance, but ultimately the mood remains muted. One can smell the countryside and breathe the fresh air in these remarkable thirty-one bars.

In 1903 Debussy heard Sousa and his band play in Paris and called him ‘the king of American music’, lauding the cakewalk as their best invention. Chouchou had the doll à la mode—a dark-skinned golliwog that first became popular in England through some children’s stories. Put them both together, and you get the Golliwog’s Cake-Walk. The music is totally characteristic of ragtime, with its syncopations and march-like beat. The humour is carried into the middle section where Debussy pokes fun at Wagner, quoting the opening of Tristan und Isolde. It is amazing how many people don’t get the joke—including the pianist who gave the premiere, Harold Bauer. Debussy said, upon first hearing him play it: “You don’t seem to object today to the manner in which I treat Wagner.” Bauer had no idea what he was talking about, until the “pitiless caricature” (as he later described it) was pointed out to him. At the premiere Debussy stayed outside the auditorium, so nervous was he of the reception the work might receive. When Bauer told him they had laughed, he gave a huge roar and was obviously relieved. His direction to play “avec une grande emotion” is, to say the least, satirical.

The Suite bergamasque has always been a favourite of mine, ever since I first played it at the age of fourteen. Its third movement is Debussy’s biggest hit, Clair de lune, but the rest is also very atmospheric and it makes a wonderful whole. It was written fifteen years before it was published in 1905, by which time Debussy’s style had changed considerably. He thus insisted on writing the date 1890 on the title page. The whole set went through many revisions and even changes of titles—Clair de lune first being called Promenade sentimentale (a good thing he changed it!), and the final Passepied starting life as Pavane.

With three movements having titles borrowed from the Baroque, it might be thought that the main influence of this suite was the music of that period—especially that of Couperin and Rameau for whom Debussy had the greatest admiration and from whom he liked to trace his musical lineage. However the biggest clue lies rather in the adjective “bergamasque.” This links it to the world of the Commedia dell’arte and also to the poet Verlaine, whose poem Clair de lune alludes to “masques et bergamasques” and an idyllic Arcadia (Debussy set this poem twice to music). Verlaine’s cycle, Fêtes galantes, was in turn inspired by the elegant and frivolous world portrayed by the painter Jean-Antoine Watteau.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zjtY8QEIkLQ

From Debussy’s Suite begamasque, ‘Passapied,’ performed by Francois-Joel Thiollier.

The opening Prélude is marked Moderato (tempo rubato), and it is important to give it the requested rhythmic freedom. Debussy, like most French composers, insisted on being faithful to his score, but realized that after exactitude comes talent. It has some beautiful changes of colour, and a great sense of space. There is an almost direct quote from Fauré’s setting of Clair de lune in bar 33. The Menuet requires good contrast between the staccato and legato touches as well as the ability to create a fanciful mood. The long sustained passage of fifteen bars before the coda has a great sense of sweep and should be played as one continuous line.

What would Debussy say if he knew his Clair de lune had been used in the soundtrack of at least fourteen major films and even in a TV commercial for Lexus automobiles (mutilated beyond belief)? It made him mad enough to be labeled an “Impressionist” composer. Of all the pieces recorded here, you could probably apply that adjective most appropriately to this masterpiece, yet it still doesn’t seem quite right. I prefer how the French pianist Jacques Février described it: ‘The first to date of the great sonorous landscapes of Debussy.’ Its hushed stillness at the beginning is almost unbearably beautiful. Thinking how to interpret it, I am reminded of what Debussy said about metronome marks and why he so rarely used them: that they are all right for one bar, “like roses for the span of a morning.” Debussy told the pianist Maurice Dumesnil to use a general flexibility in this piece, and not to confuse the harmonies by using too much pedal. The harmony in fact is the melody here—it is not just a pretty tune. The C flat that is introduced the last time the theme appears must pierce us with its feeling of regret.

The Passepied is not at all in the standard Baroque metre for this dance (3/8), but it does bring us back to the aristocratic, noble colour of the other movements. Its main difficulty lies in playing the left hand staccato while phrasing the right hand (similar to Chabrier’s Idylle and Reynaldo Hahn’s song Quand je fus pris au pavillon). Debussy evidently held back this work from the publishers for months because he wasn’t happy with the last few bars. I think he finally got them perfect.

A piano roll recorded in November 1920 on a 1920 Steinway Grand of Arthur Rubinstein performing Debussy’s ‘Danse,’ a work described by Angela Hewitt as ‘a sort of preliminary study for his later masterpiece Masques.’

Unlike many modern-day writers on Debussy, I have a soft spot for one of his first piano pieces, Danse (originally called Tarantelle styrienne). First published in 1891, it was orchestrated by Ravel in 1923. It is a sort of preliminary study for his later masterpiece Masques. The high-spirited dance rhythms of the opening are of course immensely attractive, but it is especially in the middle section that we have a whiff of what’s to come.

Debussy’s first compositions for solo piano to be issued in print were his Deux Arabesques. Already in his lifetime some 123,000 copies were sold of the first one, making it then, as now, one of his most popular pieces. It is funny to read that, even though they were published in 1891, as late as 1903 the newspaper Le Figaro published the first one as a musical supplement in which they called it a “new and entirely recent composition” by a “young composer” (Debussy was forty-one by then), stating how perplexing the music might be to even the most experienced pianist. They were no doubt trying to cash in on his success the previous year with his opera Pelléas et Mélisande, which had made him famous overnight. Now nothing seems simpler than these totally charming pieces, with their flowing and decorative writing. Debussy once used the term ‘arabesque’ in describing a movement of a Bach violin concerto, speaking of the ‘principle of “ornament”, which is the basis of all forms of art’.

From September 1959, Chilean pianist Claudio Arrau performs Debussy’s Pour le piano– Prélude

From these early works to his suite Pour le piano is a big jump. Right away we hear the difference in the writing. It’s brilliant, virtuosic, at times very sombre—with terrific pianistic effects. The Prélude begins with the opening theme hammered out in the bass, followed by a long passage over a pedal point. When the theme comes again, this time with fortissimo chords in both hands, it is joined by glissandi that Debussy wanted to be dispatched like “d’Artagnan drawing his sword.” No rubato here. There’s a beautiful shimmering middle section over a high A flat pedal in the left hand in which the right hand daubs colour on the canvas. A “Tempo di cadenza” takes up the last page with glissando-like flourishes divided between the two hands.

The Sarabande was written several years before the other movements, and Debussy revised it for inclusion in the final suite. Marked “with a slow and solemn elegance,” he said it should be “rather like an old portrait in the Louvre.” Émile Vuillermoz said Debussy played it “with the easy simplicity of a good dancer from the sixteenth century.” Indeed, it sounds both antique and modern at the same time—and it is one of my favourites among his piano works.

The final Toccata makes a triumphant ending to the suite. Debussy didn’t want speed to be the ultimate goal—to him, clarity was much more important. But there also had to be music. There is a telling story of him hearing a famous pianist play it in 1917, and, when Marguerite Long asked him about the interpretation, he replied: “Dreadful. He didn’t miss a note.” “Shouldn’t you be happy then?” she queried. “Oh, not like that,” he replied. Ricardo Viñes, who had learned of the suite from his friend Ravel, was entrusted with the premiere in January 1902. The title of the work is modest, but its importance and effect is anything but that. Many French pianists of his time commented on how important it was to approach Debussy’s piano music with the same diligence and rigour that one would apply to a Bach fugue—something that is often overlooked.

Two-and-a-half years later, in the throes of love for Emma Bardac, he wrote the final two main works on this recording: Masques and L’isle joyeuse. The latter is heard frequently; the former deserves to be better known for, in my opinion, it is as great a masterpiece. In July of 1904, Debussy sent his then wife, Lily, to stay with her father in Burgundy so that he could be with his mistress. They fled first to the island of Jersey, staying incognito at the Grand Hôtel, and then to Normandy. Masques is almost as tragic as L’isle joyeuse is triumphant. The opening repeated notes are at times muted, at times wildly percussive, giving wonderful splashes of colour. The menacing build-up before the recapitulation is thrilling. At the end the music dissolves, but not before giving us some open fifths in both hands that create the most marvelous atmosphere of something past. One reason why Debussy’s first marriage was falling apart at the time was that it was childless. A month after he wrote this piece, Lily put a bullet in her stomach, where it stayed for the rest of her life. In the scandal that followed Debussy lost many friends.

Vladimir Horowitz performs Debussy’s ‘L’isle joyeuse.’ ‘The trills and cadenza-like passage-work that open L’isle joyeuse were described as ‘a summons’ by the composer,’ Angela Hewitt writes in the liner notes to her album, Debussy: Solo Piano Music.

The trills and cadenza-like passage-work that open L’isle joyeuse were described as “a summons” by the composer. The whole piece is one long crescendo, and its tremendous energy needs to be held slightly in check, as notated by Debussy, before the final outburst of unbounded joy. For me, no one has described this work better than the pianist Marguerite Long, who studied it with Debussy: “It is a gorgeous vision, inspired with joy and prodigious exuberance: a ‘Feast of Rhythm’ in which, on the vast waves of its modulations, the virtuoso must maintain, under the sails of his imagination, the precision of his technique.” Debussy’s inspiration, besides Emma and their trip to the Isle of Jersey, was Watteau’s L’Embarquement pour Cythère (Cythera, an island in Greece, was, for the ancient world, the birthplace of Venus, goddess of love). Other than the joy given to him by his daughter Chouchou, this was probably the happiest period of his entire life.

As an “encore” to this Debussy recital, I have included the waltz La plus que lente. One of the objects on Debussy’s mantelpiece was a small sculpture, La Valse, by Camille Claudel, the mistress of Rodin, and a close friend (if not also lover) of Debussy. It remained there until his death when it mysteriously disappeared. In 1910 the gypsy fiddler Leoni played in the ballroom of the New Carlton Hotel in Paris along with his Romany band. Debussy made an arrangement for him of this “slower than slow” waltz, which is surely half parody, half serious. It is, I think, an appropriate piece with which to say farewell. —Angela Hewitt © 2012

The Critical Perspective

Angela Hewitt: ‘Her approach is light on an impressionistic wash and instead focused on rhythmically precise, elegant and unfussy details.’

‘…a reading that sees Debussy at the forefront of 20th century modernism…’

We say goodbye this week to 2012, and with it, the Debussy anniversary year. But before 2013’s anniversary celebrations of Wagner, Verdi and Britten, we consider one Debussy recording that nearly slipped under our radar.

Canadian pianist Angela Hewitt is known as one of today’s leading Bach pianists. Her devotion is so fervid that she even carried on with an all-Bach recital at Le Poisson Rouge while Hurricane Sandy was baring down on New York on the night of Oct. 28. Earlier that month, Hyperion released her collection of Debussy’s major works for solo piano: the six pieces from Children’s Corner, the four-piece Suite bergamasque, the three-piece Pour le piano, the two great Arabesques and others.

Hewitt was careful to pick works that suit her musical personality. Her approach is light on an impressionistic wash and instead focused on rhythmically precise, elegant and unfussy details. This is not the gauzy post-Romantic approach one often finds with this today’s pianists but rather a reading that sees Debussy at the forefront of 20th-century modernism.

Highlights include a rapturous Clair de lune, a colorful and witty Golliwog’s Cakewalk and tender Deux Arabesques. If the Children’s Corner suite is a little lacking in child-like charm, it is also prismatic in its color pallet. L’Isle joyeuse is exuberant from start to finish. In short, it’s a welcome release from a pianist who has risked being typecast. —WQXR.org Album of the Week, January 1, 2013

Arthur Rubinstein performs Debussy’s ‘La plus que lent.’ Angela Hewitt chose to perform this composition as the ‘encore’ on her new album, Debussy: Solo Piano Music.

‘…entrancing in neat, brightly coloured assortments’

Angela Hewitt, long a fan of French music and a stellar interpreter of the piano works of Maurice Ravel and Emmanuel Chabrier, turns her laser-like attention to Claude Debussy (1862-1918) in her latest album for Hyperion.

Like Maggie Smith, Hewitt has been careful to choose this particular musical role astutely, picking pieces that suit her style of playing. This makes for a rewarding listening experience, even though Hewitt lacks the deep, sensual touch that turns Debussy’s compositions into acts of aural seduction.

We get impeccably articulated, limpid, fleet and buttoned-down-elegant readings of 80 minutes’ worth of Debussy favourites: the six pieces from Children’s Corner, the four-piece Suite bergamasque, the three-piece Pour le piano, the two great Arabesques, Danse, Masques, L’isle joyeuse and, as a delicate encore, the waltz known as La plus que lente.

This is Debussy as a sunfish gliding under the surface of a perfectly clear lake. The music is entrancing in neat, brightly coloured assortments. –John Terauds, Musical Toronto, Oct. 14, 2012

‘…undeniably high-class playing, even when you don’t agree with some of its details.’

…this is Debussy portrayed in clean, bright colours and sharply focused detail, with every rhythm precisely etched. At times it can even seem a bit too brisk and business-like. Children’s Corner is short on child-like charm and sentiment–it would need a pretty somnolent elephant to fall asleep to this account of Jimbo’s Lullaby–while the luscious slow waltz of La Plus que Lente is turned into a rather chaste negotiation. But the clarity that Hewitt brings to the three movements of Pour le Piano, her unfussy presentation of Suite Bergamasque and the pinpoint accuracy with which she channels the energy of both L’Isle Joyeuse and the much less well-known Masques are all admirable; it’s undeniably high-class playing, even when you don’t agree with some of its details. –Andrew Clements, The Guardian, Oct. 4, 2012

‘…utterly persuasive in the three suites at its heart…’

This is one of the better offerings for Debussy’s 150th anniversary … It should come as no surprise that Hewitt is a remarkably fine Debussy pianist. This generously filled disc finds Hewitt utterly persuasive in the three suites at its heart … Hyperion captures the sound marvelously … Special mention should be made of Clair de lune: it is quite an achievement for its lyrical beauty to be heard afresh’ –BBC Music Magazine

‘…the playing is most distinguished…’

This is a Debussy recital that will delight aficionados of the piano as well as those coming to the music for the first time … The playing is most distinguished … The Passepied, with its left-hand staccato phrases, is a perfect example of the Fazioli’s velvety touch –International Record Review