Air a-gittin’ cool an’ coolah,

Frost a-comin’ in de night,

Hicka’ nuts an’ wa’nuts fallin’,

Possum keepin’ out o’ sight.

Tu’key struttin’ in de ba’nya’d,

Nary step so proud ez his;

Keep on struttin’, Mistah Tu’key,

Yo’ do’ know whut time it is.

Cidah press commence a-squeakin’

Eatin’ apples sto’ed away,

Chillun swa’min’ ‘roun’ lak ho’nets,

Huntin’ aigs ermung de hay.

Mistah Tu’key keep on gobblin’

At de geese a-flyin’ souf,

Oomph! dat bird do’ know whut’s comin’;

Ef he did he’d shet his mouf.

Pumpkin gittin’ good an’ yallah

Mek me open up my eyes;

Seems lak it’s a-lookin’ at me

Jes’ a-la’in’ dah sayin’ “Pies.”

Tu’key gobbler gwine ‘roun’ blowin’,

Gwine ‘roun’ gibbin’ sass an’ slack;

Keep on talkin’, Mistah Tu’key,

You ain’t seed no almanac.

Fa’mer walkin’ th’oo de ba’nya’d

Seein’ how things is comin’ on,

Sees ef all de fowls is fatt’nin’-

Good times comin’ sho’s you bo’n.

Hyeahs dat tu’key gobbler braggin’,

Den his face break in a smile-

Nebbah min’, you sassy rascal,

He’s gwine nab you atter while.

Choppin’ suet in de kitchen,

Stonin’ raisins in de hall,

Beef a-cookin’ fu’ de mince meat,

Spices groun’-I smell ’em all.

Look hyeah, Tu’key, stop dat gobblin’,

You ain’ luned de sense ob feah,

You ol’ fool, yo’ naik’s in dangah,

Do’ you know Thanksgibbin’s hyeah?

Originally published in Lyrics of a Lowly Life (1897)

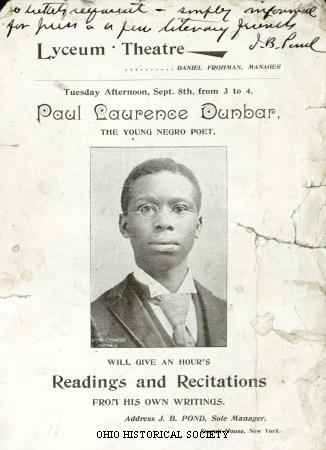

‘An excellent example of Mr. Dunbar’s roguish humor’

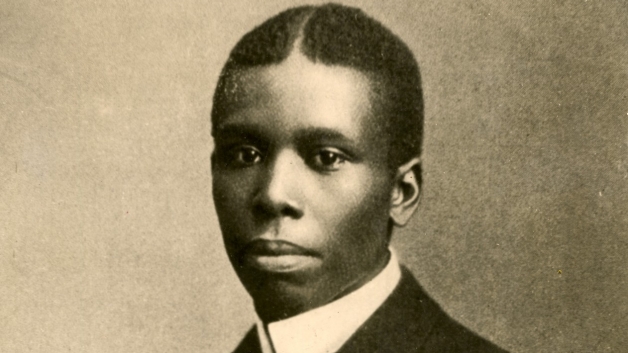

Born in Dayton, Ohio, seven years after the end of the Civil War to two former Kentucky slaves, Paul Laurence Dunbar was initially educated by his mother, who encouraged his early interest in literature. (His father, who escaped to Canada before the war and served with the Massachusetts 55th Regiment, divorced his mother soon after his birth and died when Paul was only twelve.) Dunbar was the only black student in his class at Dayton’s Central High, where he was editor of the school paper and the class poet. While he was still in school, he founded a paper, the short-lived Dayton Tattler that supported the Republican Party and covered the concerns of African Americans. The friend and classmate who operated the printing press was none other than future aviator Orville Wright.

Over the next few years, Dunbar worked as an elevator operator and, briefly, as a clerk to Frederick Douglass in Chicago. In 1893 Dunbar self-published his first collection of poems; he hand-sold every copy, and earned back his investment. Two years later, this time sponsored by white patrons, his second book, Majors and Minors, was published by a regional printer and eventually fell into the hands of William Dean Howells, the influential editor, novelist, and critic. Howells wrote an appreciation in Harper’s Magazine, praising Dunbar as “the only man of pure African blood and of American civilization to feel the negro life aesthetically and express it lyrically.” (Many commentators made much of the fact that Dunbar’s ancestry was wholly African rather than multiracial.)

The review made Dunbar suddenly–and unexpectedly–famous. Overwhelmed with gratitude, the young poet wrote Howells:

Now from the depths of my heart I want to thank you. You yourself do not know what you have done for me. I feel much as a poor, insignificant, helpless boy would feel to suddenly find himself knighted. . . .

In the collection that Howells reviewed, the “majors” were the poems written in standard English; the “minors” were dialect pieces, many of them humorous. When Howells revised his essay for the introduction of Dunbar’s third book, Lyrics of Lowly Life (1896), he made clear which he preferred:

In nothing is his essentially refined and delicate art so well shown as in these [dialect] pieces. . . . Some of [the poems in literary English] I thought very good, and even more than very good, but not distinctively his contribution to the body of American poetry. What I mean is that several people might have written them; but I do not know any one else who could quite have written the dialect pieces.

The result of Howell’s recommendation was popular demand for Dunbar’s trademark dialect poems; he soon found it difficult to publish anything else. Nevertheless, before his life was cut short by tuberculosis at the age of thirty-three, he managed to publish a dozen volumes of poetry, four collections of short stories, and four novels, and he wrote the lyrics for In Dahomey, a minstrel- and vaudeville-influenced comedy that was the first full-length Broadway musical composed and performed by African Americans.

Dunbar’s Thanksgiving poem “Sign of the Times” was described by a contemporary reviewer as “an excellent example of Mr. Dunbar’s roguish humor.”

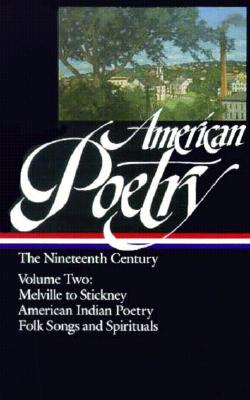

Other poems by Paul Dunbar are included in the Library of America’s new volume, American Poetry: The Nineteenth Century, volume two: Melville to Stickney, American Indian Poetry, Folk Songs and Spirituals. This second volume of The Library of America’s two-volume collection of nineteenth-century American poetry follows the evolution of American poetry from the monumental mid-century achievements of Herman Melville and Emily Dickinson to the modernist stirrings of Stephen Crane and Edwin Arlington Robinson. The cataclysm of the Civil War-reflected in fervent antislavery protests, in marching songs, and poetic calls to arms, and in muted post-bellum expressions of grief and reconciliation-ushered in a period of accelerating change and widening regional perspectives.

Parodies, dialect poems, song lyrics, and children’s verse evoke the liveliness of an era when poetry was accessible to all. Here are poems that played a crucial role in American public life, whether to arouse the national conscience (Edwin Markham’s “The Man with the Hoe”) or to memorialize the golden age of the national pastime (Ernest Lawrence Thayer’s “Casey at the Bat”).

An entire section of this volume is devoted to American Indian poetry in nineteenth-century versions, making available-some for the first time since their initial publication-an impressive range of translations and adaptations: Ojibwa healing rituals, the songs of the Ghost Dance religion, Zuni mythological narratives, chants from the Kwakiutl Winter Ceremonial. Also included is a generous selection from America’s rich heritage of anonymous folk songs, ballads, and hymns.

The anthology includes newly researched biographical sketches of each poet, a year-by-year chronology of poets and poetry from 1800 to 1900, and extensive notes.