HODDER & STOUGHTON

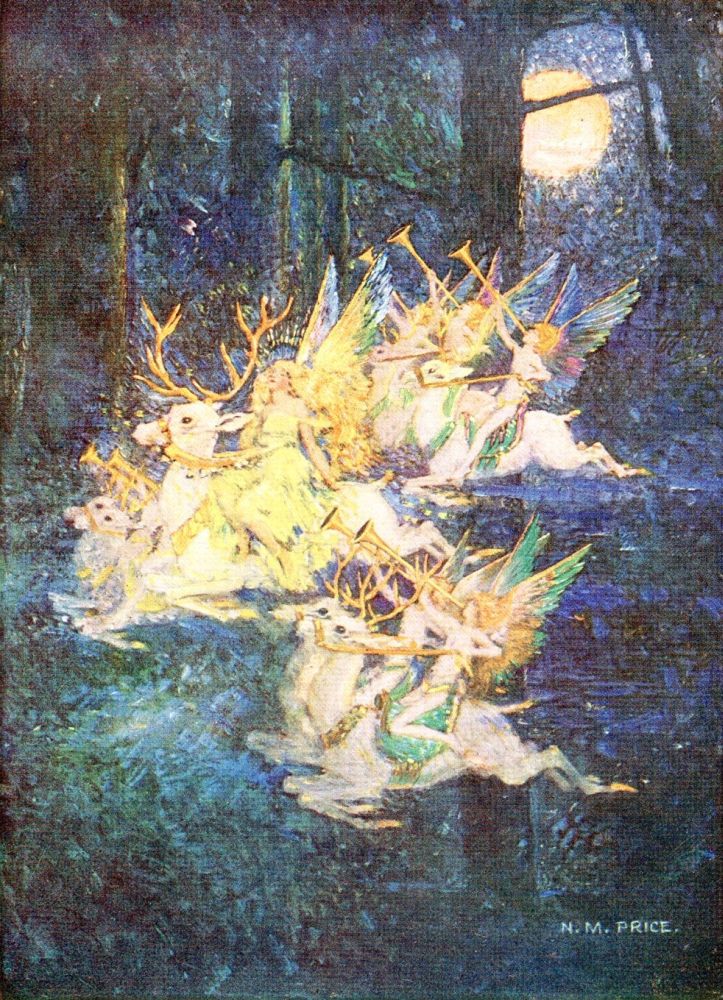

Painting by N. M. Price. FIRST WALPURGIS NIGHT.

“Through the night-gloom lead and follow

In and out each rocky hollow.”

A DAY WITH MENDELSSOHN.

During the year 1840 I visited Leipzig with letters of introduction from Herr Klingemann of the Hanoverian Legation in London. I was a singer, young, enthusiastic, and eager—as some singers unfortunately are not—to be a musician as well. Klingemann had many friends among the famous German composers, because of his personal charm, and because his simple verses had provided them with excellent material for the sweet little songs the Germans love so well. I need scarcely say that the man I most desired to meet in Leipzig was Mendelssohn; and so, armed with Klingemann’s letter, I eagerly went to his residence—a quiet, well-appointed house near the Promenade. I was admitted without delay, and shown into the composer’s room. It was plainly a musician’s work-room, yet it had a note of elegance that surprised me. Musicians are not a tidy race; but here there was none of the admired disorder that one instinctively associates with an artist’s sanctum. There was no litter. The well-used pianoforte could be approached without circuitous negotiation of a rampart of books and papers, and the chairs were free from encumbrances. On a table stood some large sketch-books, one open at a page containing an excellent landscape drawing; and other spirited sketches hung framed upon the walls. The abundant music paper was perhaps the most strangely tidy feature of the room, for the exquisitely neat notation that covered it suggested the work of a careful copyist rather than the original hand of a composer. I could not refrain from looking at one piece. It was a very short and very simple Adagio cantabile in the Key of F for a solo pianoforte. It appealed at once to me as a singer, for its quiet, unaffected melody seemed made to be sung rather than to be played. The “cantabile” of its heading was superfluous—it was a Song without Words, evidently one of a new set, for I knew it was none of the old. But the sound of a footstep startled me and I guiltily replaced the sheet. The door opened, and I was warmly greeted in excellent English by the man who entered. I had no need to be told that it was Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy himself.

Nature is strangely freakish in her choice of instruments for noble purposes. Sometimes the delicate spirit of creative genius is housed in a veritable tenement of clay, so that what is within seems ever at war with what is without. At times the antagonism is more dreadful still, and the artist-soul is sent to dwell in the body of a beast, coarse in speech and habit, ignorant and dull in mind, vile and unclean in thought. But sometimes Nature is generous, and makes the body itself an expression of the informing spirit. Mendelssohn was one of these almost rare instances. In him, artist and man were like a beautiful picture appropriately framed. He was then thirty-one. In figure he was slim and rather below the middle height, and he moved with the easy grace of an accomplished dancer. Masses of long dark hair crowned his finely chiselled face; but what I noticed first and last was the pair of lustrous, dark brown eyes that glowed and dilated with every deep emotion. He had the quiet, assured manner of a master; yet I was not so instantly conscious of that, as of an air of reverence and benignity, which, combined with the somewhat Oriental tendency of feature and colour, made his whole personality suggest that of a young poet-prophet of Israel.

“So,” he said, his English gaining piquancy from his slight lisp, “you come from England—from dear England. I love your country greatly. It has fog, and it is dark, too, for the sun forgets to shine at times; but it is beautiful—like a picture, and when it smiles, what land is sweeter?”

“You have many admirers in England, sir,” I replied; “perhaps I may rather say you have many friends there.”

“Yes,” he said, with a bright smile, “call them friends, for I am a friend to all England. Even in the glowing sun of Italy I have thought with pleasure of your dear, smoky London, which seems to wrap itself round one like a friendly cloak. It was England that gave me my first recognition as a serious musician, when Berlin was merely inclined to think that I was an interesting young prodigy with musical gifts that were very amusing in a young person of means.”

“You have seen much of England, have you not, sir?” I asked.

“A great deal,” he replied, “and of Scotland and Wales, too. I have heard the Highland pipers in Edinburgh, and I have stood in Queen Mary’s tragic palace of Holyrood. Yes, and I have been among the beautiful hills that the great Sir Walter has described so wonderfully.”

“And,” I added, “music-lovers do not need to be told that you have also penetrated

The silence of the seas

Among the farthest Hebrides.'”

“Ah!” he said, smiling, “you like my Overture, then?”

Felix Mendelssohn, Hebrides Overture (Fingal’s Cave), Op. 26, London Symphony Orchestra, Claudio Abbado (Conductor)

I hastened to assure him that I admired it greatly; and he continued, with glowing eyes: “What a wonder is the Fingal’s Cave—that vast cathedral of the seas, with its dark, lapping waters within, and the brightness of the gleaming waves outside!”

Almost instinctively he sat down at the piano, and began to play, as if his feelings must express themselves in tones rather than words. His playing was most remarkable for its orchestral quality. Unsuspected power lay in those delicate hands, for at will they seemed able to draw from the piano a full orchestral volume, and to suggest, if desired, the peculiar tones of solo instruments.

This Overture of his is made of the sounds of the sea. There is first a theme that suggests the monotonous wash of the waters and the crying of sea-birds within the vast spaces of the cavern. Then follows a noble rising passage, as if the spirit of the place were ascending from the depths of the sea and pervading with his presence the immensity of his ocean fane. This, in its turn, is succeeded by a movement that seems to carry us into the brightness outside, though still the plaint of crying birds pursues us in haunting monotony. It is a wonderful piece, this Hebrides Overture, with all the magic and the mystery of the Islands about it.

“That is but one of my Scottish impressions,” said Mendelssohn; “I have many more, and I am trying to weave them into a Scottish Symphony to match the Italian.”

“You believe in a programme then?” I asked.

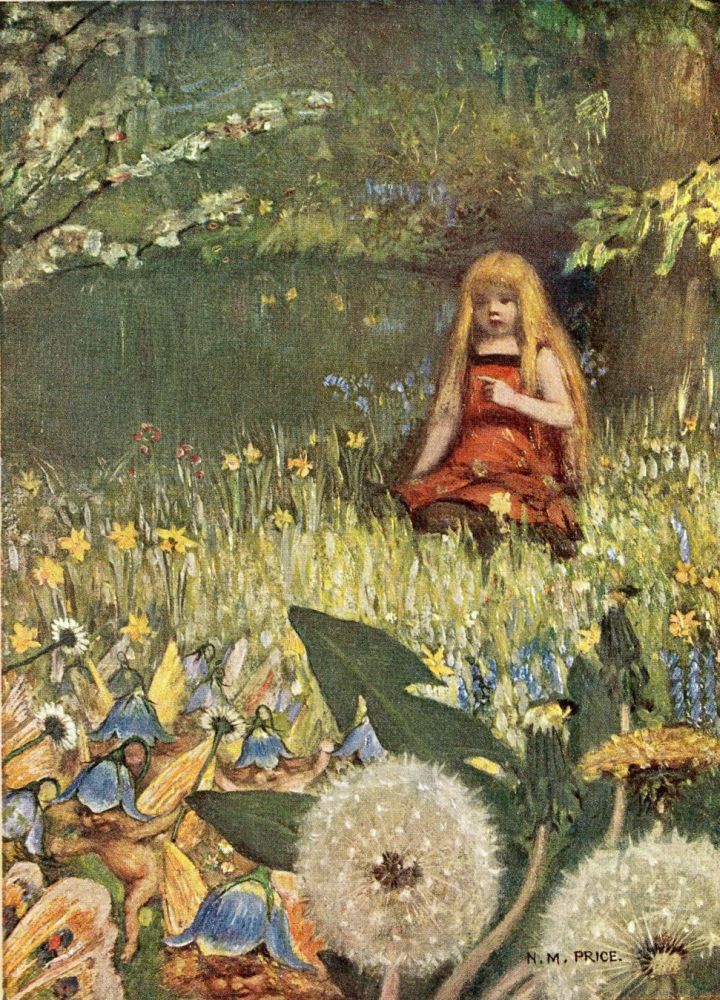

Painting by N. M. Price. SPRING SONG (Lied Ohne Worte).

“To think of it is to be happy with the innocence of pure joy.”

“Oh, yes!” he answered; “moreover I believe that most composers have a programme implicit in their minds, even though they may not recognise it. But always one must keep within the limits of the principle inscribed by Beethoven at the head of his Pastoral Symphony, ‘More an expression of the feelings than a painting.’ Music cannot paint. It is on a different plane of time. A painting must leap to the eye, but a musical piece unfolds itself slowly. If music tries to paint it loses its greatest glory—the power of infinite, immeasurable suggestion. Beethoven, quite allowably, and in a purely humorous fashion, used a few touches of realism; but his Pastoral Symphony is not a painting, it is not even descriptive; it is a musical outpouring of emotion, and enshrines within its notes all the sweet peaceful brightness of an early summer day. To think of it,” he added, rising in his enthusiasm, “is to be happy with the innocence of pure joy.”

I was relieved of the necessity of replying by a diversion without the door. Two male voices were heard declaiming in a sort of mock-melodramatic duet, “Are you at home, are you at home? May we enter, may we enter?”

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SUDvZaMl4RU

Mendelssohn, A Midsummer Night’s Dream Overture, Op. 21. Gewandhausorchester Leipzig, Kurt Masur (Conductor), Live at Gewandhaus, Leipzig

“Come in, you noisy fellows,” exclaimed Mendelssohn gaily; and two men entered. The elder, who was of Mendelssohn’s age, carried a violin case, and saluted the composer with a flourish of the music held in his other hand. “Hail you second Beethoven!” he exclaimed. Suddenly he observed my presence and hushed his demonstrations, giving me a courteous, and humorously penitent salutation. Mendelssohn introduced us.

“This,” he said to me “is Mr. Ferdinand David, the great violinist and leader of our orchestra; and this,” indicating the younger visitor, “is a countryman of yours, Mr. Sterndale Bennett. We think a great deal of Mr. Bennett in Leipzig.”

“Ah, ha!” said David to me; “you’ve come to the right house in Leipzig if you’re an Englishman. Mendelssohn dotes on you all, doesn’t he, Bennett?”

“Yes,” said Bennett, “and we dote on him. I left all the young ladies in England singing ‘Ist es wahr.'”

“Ist es wahr? ist es wahr?” carolled David, in lady-like falsetto, with comic exaggeration of anguish sentiment.

Bennett put his hands to his ears with an expression of anguish, saying, “Spare us, David; you play like an angel, but you sing like—well, I leave it to you?”

“And I forgot to mention,” said Mendelssohn with a gay laugh, “that our young English visitor is a singer bringing ecstatic recommendations from Klingemann.”

“Ah! a rival!” said David, with a dramatic gesture; “but since we’re all of a trade, perhaps our friend will show he doesn’t mind my nonsense by singing this song to us.”

“Yes,” said Mendelssohn, with a graceful gesture, “I shall be greatly pleased if you will.”

I could not refuse. Mendelssohn sat down at the piano and I began the simple song that has helped so many English people to appreciate the beauties of the German lied.

“Can it be? Can it be?

Dost thou wander through the bower,

Wishing I was there with thee?

Lonely, midst the moonlight’s splendour,

Dost thou seek for me?

Can it be? Say!

But the secret rapturous feeling

Ne’er in words must be betrayed;

True eyes will tell what love conceals!”

“Thank you very much,” said Mendelssohn with a smile.

“Bravo!” exclaimed David; “but our Mendelssohn can do more than make pretty songs. This,” he continued, indicating the music he had brought, “is going to be something great!”

Itzhak Perlman, Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto, 1st movement, with Daniel Barenboim and the Berliner Philharmoniker. Felix Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto in E minor, Op. 64 is his last large orchestral work. It forms an important part of the violin repertoire and is one of the most popular and most frequently performed violin concertos of all time.

Mendelssohn originally proposed the idea of the violin concerto to Ferdinand David, a close friend and then concertmaster of the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra. Although conceived in 1838, the work took another six years to complete and was not premiered until 1845. During this time, Mendelssohn maintained a regular correspondence with David, seeking his advice with the concerto. The work itself was one of the violin concertos of the Romantic era and was influential to the compositions of many other composers. Although the concerto consists of three movements in a standard fast–slow–fast structure and each movement follows a traditional form, the concerto was innovative and included many novel features for its time. Distinctive aspects of the concerto include the immediate entrance of the violin at the beginning of the work and the linking of the three movements with each movement immediately following the previous one.

Itzhak Perlman, Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto, 2nd movement, with David Zinman conducting the New York Philharmonic Orchestra.

Itzhak Perlman, Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto, 3rd movement, with David Zinman conducting the New York Philharmonic Orchestra.

“Do you think so?” asked Mendelssohn quietly, yet with eyes that gleamed intensely.

“I’m sure of it,” said David emphatically. “There is plenty of music for violin and orchestra—oceans of it; but there has been hitherto only one real great big Concerto,”—he spread his arms wide as he spoke. “Now there will be two.”

“No, no!” exclaimed Mendelssohn quickly; “if I finish this Concerto it will be with no impious intention of competing with Beethoven. You see, for one thing, I have begun it quite differently.”

“Yes,” nodded David, and he began to drum on the table in the rhythm of Beethoven’s fateful knocking at the door; “yes, Beethoven was before all a symphonist—his Concerto is a Symphony in D major with violin obbligato.”

“Observe,” murmured Bennett, “the blessing of a musical temperament. A drunken man thumps monotonously at his door in the depths of night. To an Englishman it suggests calling the police; to Beethoven it suggests a symphony.”

“Well, David,” said Mendelssohn, “it’s to be your Concerto, so I want you to discuss it with me in all details. I am the most devoted admirer of your playing, but I have, as well, the sincerest respect for your musicianship.”

“Thank you,” said David with a smile of deep pleasure; and turning to me he added, “I really called to play this over with the master. Shall you mind if I scratch it through?”

I tried to assure him of the abiding pleasure that I, a young stranger, would receive from being honoured by permission to remain.

“Oh, that’s all right,” he said unaffectedly; “we are all in the trade, you know; you sing, I play.”

Mendelssohn sat at the piano and David tuned his instrument. Mendelssohn used no copy. His memory was prodigious. The violin gave out a beautiful melody that soared passionately, yet gracefully, above an accompaniment, simple at first, but growing gradually more intense and insistent till a great climax was reached, after which the solo voice sank slowly to a low, whispering murmur, while the piano played above it a succession of sweetly delicate and graceful phrases. The movement was worked out with the utmost complexity and brilliance, but came suddenly to an end. The playing of the two masters was beyond description.

“The cadenza is subject to infinite alteration,” remarked Mendelssohn; and turning to me, he continued, “the movement is unfinished, you see; and even what is written may be greatly changed. I fear I am a fastidious corrector. I am rarely satisfied with my first thoughts.”

“Well, I don’t think much change is wanted here,” said David. “I’m longing to have the rest of it. When will it be ready?”

Mendelssohn shook his head with a smile. “Ask me for it in five years, David.”

“What do you think of it, Bennett?” asked the violinist.

“I was thinking that we are in the garden of Eden,” said Bennett, oracularly.

“What do you mean?” asked Mendelssohn.

“This,” explained Bennett: “there seems to me something essentially and exquisitely feminine about this movement, just as in Beethoven’s Concerto there is something essentially and heroically masculine. In other words, he has made the Adam of Concertos, and you have mated it with the Eve. Henceforth,” he continued, waving his hands in benediction, “the tribe of Violin Concertos shall increase and multiply and become as the stars of heaven in multitude.”

Mendelssohn’s String Quartet in F minor, Op. 80, mvmt. 1, as performed by the Jupiter Quartet at the awards ceremony for the 2008 Avery Fischer career grants. Live from the Rose Studio at Lincoln Center. Composed in 1847, this composition is essentially his last major composition (he died only two months after its completion). Composed after the death of his sister Fanny, the piece is powerful and highly emotive.

“The more the merrier,” cried David, “at least for fiddlers—I don’t know what the audiences will think.”

“Audiences don’t think—at least, not in England,” said Bennett.

“Come, come!” interposed Mendelssohn; and turning to me with a smile he said, “Will you allow Mr. Bennett to slander your countrymen like this?”

“But Mr. Bennett doesn’t mean it,” I replied; “he knows that English audiences love, and are always faithful to, what stirs them deeply.”

“Yes; but what does stir them deeply?” he asked; “look at the enormous popularity of senseless sentimental songs.”

“On the other hand,” I retorted, “look at our old affection for Handel and our new affection for Mr. Mendelssohn himself.”

“Thank you,” said Mendelssohn, with a smile; “Handel is certainly yours by adoption. You English love the Bible, and Handel knew well how to wed its beautiful words to noble music. He was happy in having at his command the magnificent prose of the Bible and the magnificent verses of Milton. I, too, am fascinated by the noble language of the Scriptures, and I have used it both in the vernacular and in the sounding Latin of the Vulgate. And I am haunted even now by the words of one of the Psalms which seem to call for an appropriate setting. You recall the verses?

“Hear my prayer; O God;

and hide not thyself from my petition.

Take heed unto me, and hear me,

how I mourn in my prayer and am vexed.

The enemy crieth so, and the ungodly cometh on so fast;

for they are minded to do me some mischief,

so maliciously are they set against me.

My heart is disquieted within me;

and the fear of death is fallen upon me.

Fearfulness and trembling are come upon me;

and a horrible dread hath overwhelmed me.

And I said, O that I had wings like a dove;

for then would I flee away, and be at rest.

Lo, then would I get me away far off;

and remain in the wilderness.

I would make haste to escape;

because of the stormy wind and tempest.”

“Yes,” said David, nodding emphatically; “they are wonderful words; you must certainly set them.”

“The Bible is an inexhaustible mine of song and story for musical setting,” continued Mendelssohn; “I have one of its stories in my mind now; but only one man, a greater even than Handel, was worthy to touch the supreme tragedy of all.”

The last words were murmured as if to himself rather than to us, and he accompanied them abstractedly with tentative, prelusive chords, which gradually grew into the most strangely moving music I have ever heard.

Its complex, swelling phrases presently drew together and rose up in one great major chord. No one spoke. I felt as if some mighty spirit had been evoked and that its unseen presence overshadowed us.

“What was it?” I presently whispered to Bennett; but he shook his head and said, “Wait; he will tell you.”

At length I turned to Mendelssohn and said, “Is that part of the new work of yours you mentioned just now?”

“Of mine!” he exclaimed; “of mine! I could never write such music. No, no! That was Bach, John Sebastian Bach—part of his St. Matthew Passion. I was playing not so much the actual notes of any chorus, but rather the effect of certain passages as I could feel them in my mind.”

“So that was by Bach!” I said in wonder.

“Yes,” said Mendelssohn; “and people know so little of him. They either think of him as the composer of mathematical exercises in music, or else they confuse him with others of his family. He was Cantor of the St. Thomas School here in Leipzig, the perfect type of a true servant of our glorious art. He wrote incessantly, but the greatest of his works lay forgotten after his death; and it was I, I, who disinterred this marvellous music-drama of the Passion, and gave it in Berlin ten years ago—its first performance since Bach’s death almost a century before. But there,” he added, with an apologetic smile, “I talk too much! Let us speak of something else.”

St. Paul’s Choir sings ‘Hark the Herald Angels Sing.’ In 1855, English musician William H. Cummings adapted Felix Mendelssohn’s secular music from the composer’s Festgesang (Gutenberg cantata) to fit the lyrics of ‘Hark! The Herald Angels Sing’ written by Charles Wesley. Wesley envisioned the song being sung to the same tune as his song ‘Christ the Lord Is Risen Today,’ and in some hymnals, is included along with the more popular version. This hymn was regarded as one of the Great Four Anglican Hymns and published as number 403 in “The Church Hymn Book” (New York and Chicago, USA, 1872).

In the UK, ‘Hark! The Herald Angels Sing’ has popularly been performed in an arrangement that maintains the basic original William H. Cummings harmonization of the Mendelssohn tune for the first two verses but adds a soprano descant and a last verse harmonization for the organ in verse 3 by Sir David Willcocks. (Source: Wikipedia)

“Yes,” said David, “you will talk of Bach for ever if no one stops you. Not that I mind. I am a disciple, too.”

“And I, too,” added Bennett. “I mean to emulate Mendelssohn. He was the first to give the ‘Passion’ in Germany, I will be the first to give it in England.”

“Then I’ll be recording angel,” said David, “and register your vow. You’ll show him up, if he breaks his word, won’t you?” he added, turning to me.

“Now this will really change the subject,” said Mendelssohn, producing a sheet of manuscript. “Here is a little song I wrote last year to some old verses. Perhaps our new friend will let us hear it.”

In great trepidation I took the sheet. It was headed simply “Volkslied.” I saw at once that there would be no difficulty in reading it, for the music was both graceful and simple.

“Shall we try?” asked Mendelssohn, with his quiet, reassuring smile.

“If you are willing to let me,” I answered.

Parting.

“It is decreed by heaven’s behest

That man from all he loves the best

Must sever.

That soon or late with breaking heart

With all his dear ones he must part

For ever.

How oft we cull a budding flower,

To see it bloom a transient hour;

‘Tis gathered.

The bud becomes a lovely rose,

Its morning blush at evening goes;

‘Tis withered.

And has it pleased our God to lend

His cheering smile in child or friend?

To-morrow—

To-morrow if reclaimed again

The parting hour will prove how vain

Is sorrow.

Oft hope beguiles the friends who part;

With happy smiles, and heart to heart,

‘To meet,’ they cry, ‘we sever.’

It proves good-bye for ever

For ever!”

Painting by N. M. Price. PARTING.

“It is decreed by heaven’s behest

That man from all he loves the best

Must sever.”

“Bravo!” cried Bennett.

“Say rather, ‘Bravi,'” said David, “for the song was as sweet as the singer.”

“Yes,” said Bennett; “the simple repetition of the closing words of each verse is like a sigh of regret.”

“And the whole thing,” added David, “has the genuine simplicity of the true folk-melody.”

Mendelssohn’s ‘Volkslied,’ Op. 63, no. 5. Soprano I: Felicity Lott; Soprano II: Ann Murray; Piano: Graham Johnson. One of a series of short, lyrical piano pieces written by Mendelssohn between 1829 and 1845.

Further discussion was prevented by a characteristic knock at the door.

The visitor who entered in response to Mendelssohn’s call was a sturdily built man of thirty, or thereabouts, with an air of mingled courage, resolution, and good humour. His long straight hair was brushed back from a broad, intellectual brow, and his thoughtful, far-looking eyes intensified the impression he gave of force and original power. He smiled humorously. “All the youth, beauty and intellect of Leipzig in one room. I leave you to apportion the qualities. Making much noise, too! And did I hear the strains of a vocal recital?”

“You did,” replied Bennett; “that was my young countryman here, who has just been singing a new song of Mendelssohn’s.”

“Pardon me,” said the new-comer to me; “you see Mendelssohn so fills the stage everywhere, that even David gets over-*looked sometimes, don’t you, my inspired fiddler?” he added, slapping the violinist on the back.

“Yes I do,” said David, “and so do the manners of all of you, for no one introduces our singer;” and turning to me he added, “this is Mr. Robert Schumann who divides the musical firmament of Leipzig with Mendelssohn.”

“You forget to add,” said Mendelssohn, “that Schumann conquers in literature as well as in music. No one has written better musical critiques.”

“Yes, yes,” grumbled David; “I wish he wouldn’t do so much of it. If he scribbled less he’d compose more. The cobbler should stick to his last, and the musician shouldn’t relinquish the music-pen for the goose quill.”

“But what of Mendelssohn himself,” urged Schumann; “he, in a special sense, is a man of letters; for if there’s one thing as good as being with him, it is being away from him, and receiving his delightful epistles.”

“Not the same thing,” said David, shaking his head.

“And then,” said Schumann, waving his hand comprehensively around the room, “observe his works of art.”

I was about to express my astonishment at finding that Mendelssohn himself had produced these admirable pictures; but David suddenly addressed me: “By the way, don’t let Mendelssohn decoy you into playing billiards with him; or if you do weakly yield, insist on fifty in the hundred—unless, of course, you have misspent your time, too, in gaining disreputable proficiency;” and he shook his head at the thought of many defeats.

American soprano Agnes Kimball (1881-1918) performs ‘Hear ye, Israel’ from Mendelssohn’s opera Lorelei, which remained unfinished at his death in 1847. Ms. Kimball’s superb recording was done on September 22, 1911. Based on the legend of the Lorelei Rhine maidens; the opera included a high F-sharp in the oratorio Elijah (“Hear Ye Israel”) composed with the voice of the wildly popular Swedish soprano Jenny Lind’s voice in mind, although she did not sing this part until after Mendelssohn’s death, at a concert in December 1848. Before she married German composer Otto Goldschmidt, Linda was Mendelssohn’s great unrequited love: An affidavit from Goldschmidt, which is currently held in the archive of the Mendelssohn Scholarship Foundation at the Royal Academy of Music in London, reportedly describes Mendelssohn’s 1847 written request for Lind, who was then single, to elope with him to America. The affidavit, though unsealed, is currently unreleased by the Mendelssohn Scholarship Foundation, despite requests to make it public. Despite his affection for Lind, Mendelssohn was a devoted husband to his wife Cécile.

“Certainly,” exclaimed Schumann, “Mendelssohn does all things well.”

“That’s a handsome admission from a rival,” said David.

“A rival!” answered Schumann with spirit. “There can be no talk of rivalry between us. I know my place. Mendelssohn and I differ about things, sometimes; but who could quarrel with him?”

“I could!” exclaimed David, jumping up, and striking an heroic attitude.

“You!” laughed Schumann; “You quarrel, you dear old scraper of unmentionable strings!”

“Ah, ha! my boy,” chuckled David, “you can’t write for them.”

“You mean I don’t write for them,” said Schumann; “I admit that I don’t provide much for you to do. I leave that to my betters.”

“Never mind,” said David, giving his shoulder a friendly pat; “at least you can write for the piano. I believe in you, and your queer music.”

“That’s nice of you, David,” replied Schumann, “but as to Mendelssohn and me, who shall decide which of us is right? He believes in making music as pellucid to the hearers as clear water. Now I like to baffle them—to leave them something to struggle with. Music is never the worse for being obscure at first.”

Mendelssohn shook his head and smiled. “You state your case eloquently, Schumann,” he said, “but my feelings revolt against darkness and indefiniteness.”

“Yes, yes,” assented Schumann; “you are the Fairies’ Laureate.”

Leonard Bernstein conducts the New York Philharmonic in Mendelssohn’s Symphony No. 3 in A minor, the ‘Scottish Symphony,’ written intermittently between 1829 and 1842, when it was premiered in Leipzig.

“Hear, hear!” cried David. “Now could anything be finer in its way than the Midsummer Night’s Dream music? And the wondrous brat wrote it at seventeen!”

Mendelssohn laughingly acknowledged the compliments.

“That is a beautiful fairy song of yours,” I said, “the one to Heine’s verses about the fairies riding their tiny steeds through the wood.”

“Oh, yes,” said Schumann; “will you sing it to us?”

“I am afraid it requires much lighter singing than I can give it,” I replied; “but I will try, if you wish.”

“We shall all be glad if you will,” said Mendelssohn, as he turned once more to the key-board. The bright staccato rhythm flashed out from his fingers so gaily that I was swept into the song without time for hesitation:

The Fairy Love.

“Through the woods the moon was glancing;

There I saw the Fays advancing;

On they bounded, gaily singing,

Horns resounded, bells were ringing.

Tiny steeds with antlers growing

On their foreheads brightly glowing,

Bore them swift as falcons speeding

Fly to strike the game receding.

Passing, Queen Titania sweetly

Deigned with nods and smiles to greet me.

Means this, love will be requited?

Or, will hope by death be blighted?”

“You have greatly obliged us,” said Schumann courteously.

“It reminds me, though I don’t know why,” said David, “of that fairy-like duet about Jack Frost and the dancing flowers.”

“Come along and play it with me,” said Mendelssohn to Bennett; “you’ve been hiding your talents all day.”

Bennett joined him at the piano, and the two began to romp like schoolboys.

The simple duet was woven into a brilliant fantasia, but always in the gay spring-like spirit of the poem.

Painting by N. M. Price. THE FAIRY LOVE.

“Through the woods the moon was glancing

There I saw the fays advancing.

Tiny steeds with antlers growing

on their foreheads brightly glowing.”

The Maybells and the Flowers.

“Young Maybells ring throughout the vale

And sound so sweet and clear,

The dance begins, ye flowers all,

Come with a merry cheer!

The flowers red and white and blue

Merrily flock around,

Forget-me-nots of heavenly hue,

And violets, too, abound.

Young Maybells play a sprightly tune,

And all begin to dance,

While o’er them smiles the gentle moon,

With her soft silvery glance.

This Master Frost offended sore;

He in the vale appeared:

Young Maybells ring the dance no more—

Gone are the flowers seared!

But Frost has scarcely taken flight,

When well-known sounds we hear:

The Maybells with renewed delight,

Are ringing doubly clear!

Now I no more can stay at home,

The Maybells call me so:

The flowers to the dance all roam,

Then why should I not go?”

“Really,” said David; “it’s quite infectious”; and jumping up he began to pirouette, exclaiming, “Then why should I not go!”

“David, this is unseemly,” exclaimed Schumann, with mock severity. “There’s another pretty fairy-like piece of yours, Mendelssohn, the Capriccio in E minor.”

“Yes,” said Bennett, beginning to touch its opening fanfare of tiny trumpet-notes; “someone told me a pretty story of this piece, to the effect that a young lady gave you some flowers, and you undertook, gallantly, to write the music the Fairies played on the little trumpet-like blooms.”

“Yes,” said Mendelssohn, with a smile, “it was in Wales, and I wrote the piece for Miss Taylor.”

“By-the-by,” said Schumann, “David’s antics remind me that Mendelssohn can make Witches and other queer creatures, dance, as well as Fairies.”

“Villain,” exclaimed David, and he began to recite dramatically the invocation from the “First Walpurgis Night,” while Mendelssohn played the flashing accompaniment.

“Come with flappers,

Fire and clappers;

Hop with hopsticks,

Brooms and mopsticks;

Through the night-gloom lead and follow

In and out each rocky hollow.

Owls and ravens

Howl with us and scare the cravens.”

“Ah,” said Mendelssohn, “I don’t think the old poet would really have cared for my setting, though he admired my playing, and was always most friendly to me.”

“Yes,” said Schumann, warmly; “Goethe liked you because you were successful, and prosperous. Now Beethoven was poor: therefore Beethoven must first be loftily patronised and then contemptuously snubbed. I can never forgive Goethe for that. And as for poor Schubert, well, Goethe ignored him, and actually thought he had misinterpreted the Erl-king! It would be comic if it were not painful.”

Barbara Bonney performs Mendelssohn’s ‘Auf Flugein des Gesanges’ (‘On Wings of Song’), text by Heinrich Heine.

“Poor Schubert!” said Mendelssohn with a sigh; “he met always Fortune’s frown, never her smile.”

“Don’t you think,” said Bennett, “that his genius was the better for his poverty—that he learned in suffering what he taught in song?”

“No, I do not!” replied Mendelssohn warmly. “That is a vile doctrine invented by a callous world to excuse its cruelty.”

“I believe there’s something in it, though,” said Bennett.

“There is some truth in it, but not much,” answered Mendelssohn, his eyes flashing as he spoke. “It is true that the artist learns by suffering, because the artist is more sensitive and feels more deeply than others. But enough of suffering comes to all of us, even the most fortunate, without the sordid, gratuitous misery engendered by poverty.”

“I agree with Mendelssohn,” said Schumann. “To say that poverty is the proper stimulus of genius is to talk pernicious nonsense. Poverty slays, it does not nourish; poverty narrows the vision, it does not ennoble; poverty lowers the moral standard and makes a man sordid. You can’t get good art out of that.”

Painting by N. M. Price. THE MAYBELLS AND THE FLOWERS.

“Now I no more can stay at home.

The Maybells call me so.

The flowers to the dance all roam,

Then, why should I not go?”

“Perhaps I have been more fortunate than most artists,” said Mendelssohn softly. “When I think of all that my dear father and mother did for us, I can scarcely restrain tears of gratitude. Almost more valuable than their careful encouragement was their noble, serious common-sense. My mother, whom Heaven long preserve to me, was not the woman to let me, or any of us, live in a fool’s paradise, and my dear dead father was too good a man of business to set me walking in a blind alley. Ah!” he continued, with glistening eyes, “the great musical times we had in the dear old Berlin house!”

“Yes,” said David; “Your house was on the Leipzig Road. You see, even then, the finger of fate pointed the way to this place.”

“Indeed,” said Schumann, with a sigh, “You certainly had extraordinary opportunities. Not that I’ve been badly used, though.”

“Your father was genuinely proud of you,” said David. “I remember his epigram: ‘Once I was the son of my father; now I am the father of my son.'”

Mendelssohn nodded with a smile, and, turning to me, said in explanation, “You must know that my father’s father was a famous philosopher.”

“Well!” said Schumann, rising, “I must be going.”

Bennett and David also prepared to leave, and I rose with them.

“Wait a moment,” said Mendelssohn; and going to the door he called softly, “Cecile, are you there?”

He went out for a moment, and returned with a beautiful and charming girl, who greeted the three visitors warmly.

Mendelssohn then presented me, saying, gently and almost proudly, “This is my wife.”

I bowed deeply.

“You are from England?” said the lady, with the sweetest of smiles; “I declare I am quite jealous of your country, my husband loves it so much.”

“We are very proud of his affection,” I replied.

She turned to Schumann and said softly, “And how is Clara?”

“Oh, she is well;” he replied with a glad smile.

“And the father?” she added.

“We have been much worried,” he said gravely; “but we shall marry this year in spite of all he may do.”

“She is worth all your struggles,” said Mendelssohn warmly; “she is a charming lady, and an excellent musician. You will be very happy.”

“Thanks, thanks,” replied Schumann, with evident pleasure.

Isobel Baillie and Kathleen Ferrier sing Mendelssohn’s ‘Greeting’ accompanied by Gerald Moore on piano. Recorded in 1945.

Mendelssohn turned to me and shook my hand warmly. “I have been glad to meet you, and to hear you; for you sing like a musician. I shall not say good-bye. You will call again, I hope, before you leave Leipzig. Perhaps we may meet, too, in England. I am now writing something that I hope my English friends will like.”

“What is it, sir?” I asked.

“It is an oratorio on the subject of Elijah,” he replied.

“It is bound to be good,” said Schumann enthusiastically. “Posterity will call you the man who never failed.”

“Ah!” said Mendelssohn almost sadly, “you are all good and kind, but you praise me too much. Perhaps posterity will remember me for my little pieces rather than for my greater efforts. Perhaps it will remember me best, not as the master, but as the servant; for in my way I have tried very hard to glorify the great men who went before me—Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert—Bach most of all. Even if every note of my writing should perish, perhaps future generations will think kindly of me, remembering that it was I, the Jew by birth, who gave back to Christianity that imperishable setting of its tragedy and glory.”

With these words in my ears I passed out into the pleasant streets of Mendelssohn’s chosen city.

TRANSCRIBER’S NOTE

Contemporary spellings have been retained even when inconsistent. In a small number of cases, missing punctuation has been silently added.

The following additional changes have been made:

Lied ohne Wörte Lied ohne Worte

grateful and simple graceful and simple

Courtesy Project Gutenberg

MENDELSSOHN IN BRIEF

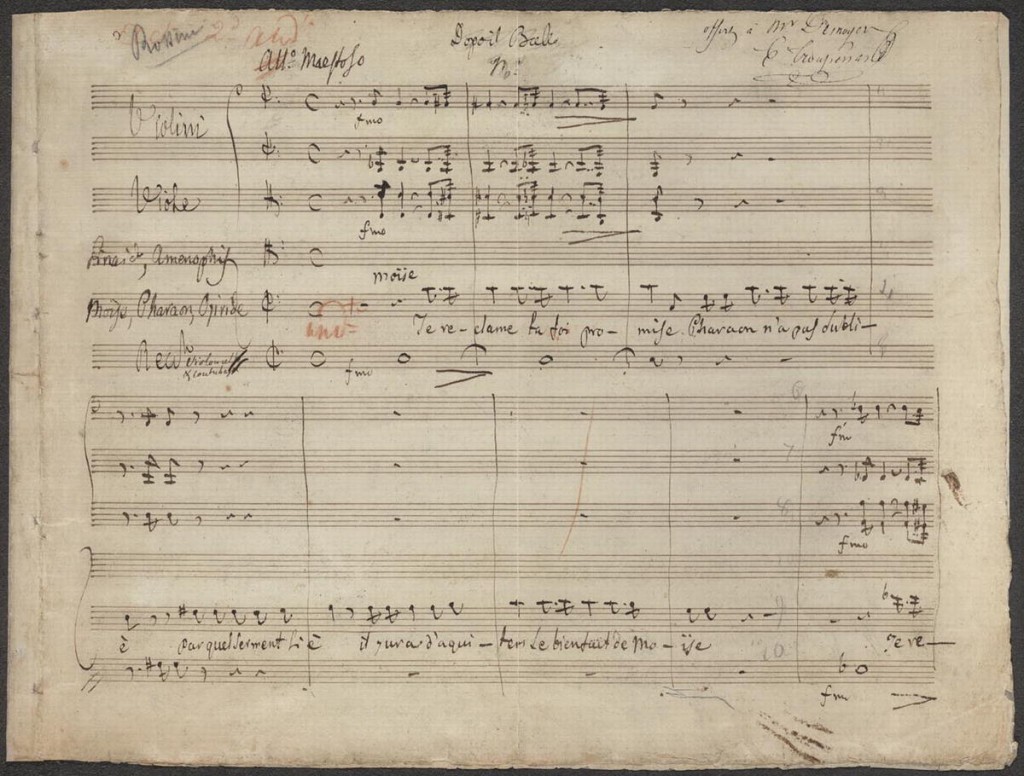

A section of Mendelssohn’s oratorio Elijah in the composer’s own hand

Beethoven heard him play in 1821 and made a prophetic entry in one of his conversation books: “Mendelssohn–12 years old–promises much.”

His piano music showcases a Mendelssohn trademark-–sounding as though written for three hands, Mendelssohn’s innate conservatism and disdain of chest-beating bravado is most strongly felt in his solo instrumental music.

Schumann’s stream-of-consciousness flights of fancy on the one hand, and Liszt’s groundbreaking pianistic innovations on the other, were creative options temperamentally closed to him.

Yet if this is the one area in which Mendelssohn struggled to find an overall niche, behind such innocent-sounding generic titles as Prelude, Fugue, Capriccio, Fantasia and Etude lie a number of cherishable gems.

It is a sign of Mendelssohn’s devotion to Bach that his single finest piano work is a set of Six Preludes and Fugues Op.35, which opens with a swirling E minor Prelude that creates the uncanny impression of being written for three hands (a favorite Mendelssohn device).

Other piano highlights include the Andante and Rondo Capriccioso Op.14 (a hyper-active template for the finales of the concertos), the Variations Sérieuses Op.54 and the Piano Sonata in E major Op.6, which develops magically upon the opening movement of Beethoven’s Sonata in A major Op.101.

Nowhere is the tantalizing innocence of Mendelssohn’s creative genius revealed more poignantly than in the eight books of Songs Without Words, 48 genial miniatures that include such favorites as Hunter’s Song Op.19, Spring Song Op.62 and Spinning Song (or Bee’s Wedding) Op.67.

Mendelssohn was one of the first mainstream Romantics to pay the organ any serious attention. He wrote a delightful series of occasional pieces that climaxed in the majestic Six Sonatas Op.65.

•Mendelssohn was born into a prosperous middle-class family that played host to many distinguished guests.

•By the time Felix was 12, he had already produced four operas, 12 string symphonies and a large quantity of chamber and piano music.

•If Mendelssohn’s early progress had been nothing short of phenomenal, no one could have predicted what was shortly to follow: an astonishingly accomplished String Octet in 1825 and, only a year later, the magical overture to A Midsummer Night’s Dream, arguably two of the most stunning displays of youthful talent in western music.

•During the summer of 1834 Mendelssohn was appointed music director of the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra.

•In 1837 he married Cecile Jeanrenaud. It was an inspired partnership, one which–to Felix’s great relief–gained the approval of Fanny and produced no fewer than five children.

In 1959, Germany honored the 150th anniversary of his birth by issuing a Felix Mendelssohn stamp.

•In 1842 Felix enjoyed his first personal contact with the young Queen Victoria and her consort, Prince Albert. In gratitude, he dedicated his ‘Scottish’ Symphony to the Queen.

•British people quickly took Felix Mendelssohn into their hearts. Indeed, such was the 37-year-old Mendelssohn’s impact in England that in 1846 he directed the first performance of his new oratorio, Elijah, as the chief attraction of the Birmingham Festival.

•In March 1847 Mendelssohn’s sister Fanny died, prematurely dealing an incalculable emotional blow to the composer. He never fully recovered, and following a slight stroke died in November of the same year. Queen Victoria was distraught: “We were horrified, astounded and distressed to read in the papers of the death of Mendelssohn, the greatest musical genius since Mozart and the most amiable man.”

•Mendelssohn was often compared with Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. Also a child prodigy, Mendelssohn had his first piano lessons at the age of six. At the age of nine, he performed music in public for the first time, and began composing works that deeply impressed authoritative musicians like Carl Friedrich Zelter.

Zelter, the head of the Berlin Singakademie, began to teach Mendelssohn counterpoint and composition, and more than anyone influenced Mendelssohn’s musical taste and style. A great admirer of Johann Sebastian Bach, Zelter made sure that his favourite student became familiar with Bach’s music techniques. Mendelssohn would later play a crucial role in reviving interest in Bach’s music that was considered old-fashioned and largely forgotten in Europe.

•Mendelssohn was one of the first conductors to use a baton to beat time when he stood in front of the orchestra.

Source: Classic FM.com

Mendelssohn: A Listener’s Incompleat Guide

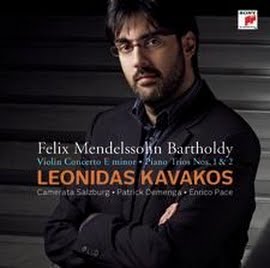

FELIX MENDELSSOHN: VIOLIN CONCERTO IN E MINOR; PIANO TRIOS NOS. 1 & 2

Leonidas Kavakos

Sony Classics (2009)

Winner of both the Sibelius and Paganini violin competitions, Leonidas Kavakos is established as one of the world’s leading violinists. He appears in concert throughout the world at many of the major international festivals specializing in chamber music and recitals.

This all-Mendelssohn disc focuses primarily on the famous Violin Concerto, which sees Kavakos joined by Camerata Salzburg (where he holds the position of Artistic Director) also included here are a couple of beautiful piano trios.

A MIDSUMMER NIGHT’S DREAM

Seiji Ojawa (conductor), Kathleen Battle (First Fairy), Frederica Von Stade (Second Fairy), Judi Dench (narrator), Tanglewood Festival Orchestra, Boston Symphony Orchestra

Deutsche Grammophon

Many commentaries on this work tend to focus on the fact that Mendelssohn wrote his Overture to A Midsummer Night’s Dream when he was only seventeen, in contrast to the rest of the incidental music, composed many years after.

And while that’s certainly true, it’s easy to marvel only at that one fact instead on focusing on how exquisite the rest of the work actually is.

Aside from the Overture, A Midsummer Night’s Dream was written in 1842. Mendelssohn’s challenge was, essentially, the nineteenth- century equivalent of composing a film score: to write music that reflected, enhanced and enlightened the acting, while never detracting from it. He was initially inspired to compose music for the play because it was a childhood favourite; to quote Mendelssohn’s sister, Fanny, “We were entwined with A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Felix particularly made it his own. He identified with all of the characters. He recreated them, so to speak, every one of them whom Shakespeare produced in the immensity of his genius”.

From the triumphant Wedding March to the impish Scherzo, via the shimmering Intermezzo and the enchanting Nocturne, this is music of which Shakespeare would surely have approved.

HEBRIDES OVERTURE (FINGAL’S CAVE), Opus 26

Claudio Abbado (conductor), London Symphony Orchestra

Deutsche Grammophon (1990)

How do you conjure up the sounds and sights of Scotland in a single piece of music? That was the challenge facing Mendelssohn when, in 1829, he travelled home from a memorable trip to the Scottish island of Staffa and its famous Fingal’s Cave.

The journey had evidently made an immediate impression on the composer: just hours later, he had written the first few bars of this piece and sent them off to his sister, Fanny, along with a note that described “How extraordinarily the Hebrides affected me.”

His travels to Scotland were part of a wider tour of Europe for Mendelssohn during his early twenties, and it’s not hard to see why he was particularly captivated by what he encountered on Staffa. Fingal’s Cave is over sixty meters deep and in stormy tides the cacophonous sounds of the waves inside it rumble out for miles. The intense and rolling melodies within the music perfectly capture this sense of both drama and awe; calmer passages, meanwhile, convey stiller waters and more tranquil surroundings. But it’s never long before the return of that stormy scene.

On completing the score, Mendelssohn triumphantly wrote “Fingal’s Cave” on the front page, leaving no room for doubt that his Hebrides Overture was wholly inspired by this awesome Scottish landscape.