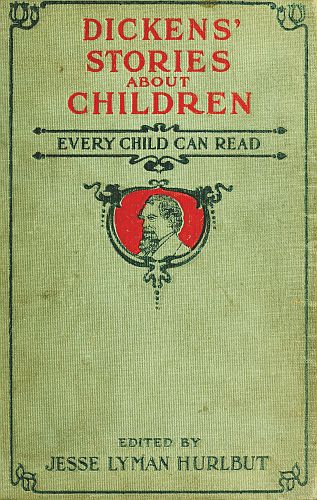

(Editor’s note: Continuing our bicentennial salute to Charles Dickens, this month’s installment features the story of Jenny Wren, from the author’s last published novel, Our Mutual Friend. Homely and disabled, young Jenny is the only child of an alcoholic father, and Dickens uses her to illustrate the damage adult alcoholics can inflict on their offspring. As sorrowful tale but one not lacking a sense of hope, “Jenny Wren” is vividly drawn and altogether unforgettable. “Jenny Wren” was first anthologized in the Rev. Jesse Lyman Hurlburt’s 1909 collection titled Dickens’ Stories About Children Every Child Can Read.)

In Our Mutual Friend, Dickens takes a wry look at class attitudes in nineteenth-century England against the backdrop of the sanitary movement, but this is not the only social ill under scrutiny. In the chapter “Presentation of Characters,” E. D. H. Johnson writes: “The victimized child is a recurrent figure in Dickens’ fiction from his earliest work; but in the mature novels the all but universal neglect or abuse of children by their parents is systematically elaborated as one of the signs of the times.”

At least one cause of this systematic abuse and neglect was alcohol. Cleverly woven in between the intrigues at Boffin’s Bower and the social dinners at the Veneerings, is the story of the doll’s dressmaker Jenny Wren and her father. Using Jenny as his canvas, Dickens creates a startlingly graphic representation of the effects of adult alcoholism on children.

The novelist Henry James took a special disliking to Jenny Wren, declaring in a review, “Like all Mr. Dickens’s pathetic characters, she is a little monster. She belongs to the troop of hunchbacks, imbeciles, and precocious children, who have carried on the sentimental business in all Mr. Dickens’s novels, the little Nells, the Smikes the Paul Dombeys.”

However, there is nothing sentimental about Jenny’s business. In order to understand Jenny, one must also consider the father. In Working With Children of Alcoholics, Bryan Robinson writes, “No family member can be understood in isolation from the other members of the family system”; “the same is true of an alcoholic family.” Jenny is the daughter of an alcoholic; she has been surrounded by alcoholic adults all of her life. Her friend Lizzie explains to Charley that Jenny’s “father is like his own father, a weak wretched trembling creature, falling to pieces, never sober. . . . The mother is dead. This poor ailing little creature has come to be what she is, surrounded by drunken people from her cradle – if she ever had one, Charley.”

In light of this information, Jenny’s behavior appears more logical than monstrous.

A cradle is not the only thing Jenny has never had. Surrounded by alcoholic adults for the twelve years of her life, she has never had a childhood. In Adult Children of Alcoholics, Janet Woititz writes, “When is a child not a child? When the child lives with alcoholism.” Children of alcoholics, who grow up early, take over the responsibilities their alcoholic parents have abdicated. In “Alcoholism and the Family,” Robert J. Ackerman explains how these children tend to adopt adult roles: “When parents are unable or unwilling to assist in the home, their children consistently may be forced to organize and run the household. They may be picking up after their parents, and assuming extremely mature roles for their ages.” Robinson states it more bluntly: “Ultimately, they miss childhood altogether.”

In the character of Jenny Wren, Dickens displays an uncanny awareness of the effects of adult alcoholism on children. Every aspect of Jenny’s character is defined by her father’s drinking. She may not be a “little monster,” but neither is she a “cortable” character. She is not supposed to be. Rather, she is a goad, a pebble in the shoe, or maybe even a frighteningly accurate mirror meant to illustrate in startling detail what can happen to alcoholics and their children.

For more on how the actions and behavior of Jenny Wren reflect the effects of adult alcoholism on children, see the Jenny Wren entry at The Victorian Web.

Although not specifically about Dickens’s Jenny Wren, Paul McCartney’s touching 2005 Grammy-nominated performance of his song titled “Jenny Wren,” from his album Chaos and Creation in the Backyard, references some of the Dickens’ character’s most affecting traits, right up to and including a poignant demise that is at once sad and hopeful.

Directly and unambiguously inspired by Dickens’s creation Melissa Coker of Lake Forest, Illinois, founded a fashion line called Wren in 2007. Jenny Wren served as the first muse for the label and its dedication to perfect imperfection. In an interview with Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, Ms. Coker explained her fascination with Jenny Wren thusly: “She is this almost gothic, victorian little creature who makes dresses for dolls. I just loved the idea of this winsome thing with such a dark side. It was the contrast there that I found really appealing.”

Dickens’ Stories About Children Every Child Can Read

Edited by Rev. Jesse Lyman Hurlbut, D.D.

Illustrated

Every Child’s Library

THE JOHN C. WINSTON CO.

PHILADELPHIA

Copyright, 1909, By The John C. Winston Co.

JENNY WREN

WALKING into the city one holiday, a great many years ago, a gentleman ran up the steps of a tall house in the neighborhood of St. Mary Axe. The lower windows were those of a counting-house but the blinds, like those of the entire front of the house, were drawn down.

The gentleman knocked and rang several times before any one came, but at last an old man opened the door. “What were you up to that you did not hear me?” said Mr. Fledgeby irritably.

“I was taking the air at the top of the house, sir,” said the old man meekly, “it being a holiday. What might you please to want, sir?”

“Humph! Holiday indeed,” grumbled his master, who was a toy merchant amongst other things. He then seated himself in the counting-house and gave the old man–a Jew and Riah by name–directions about the dressing of some dolls about which he had come to speak, and, as he rose to go, exclaimed–

“By-the-by, how do you take the air? Do you stick your head out of a chimney-pot?”

“No, sir, I have made a little garden on the leads.”

“Let’s look it at,” said Mr. Fledgeby.

“Sir, I have company there,” returned Riah hesitating, “but will you please come up and see them?”

Seated on a carpet, and leaning against a chimney-stack, were two girls bending over books.

Mr. Fledgeby nodded, and, passing his master with a bow, the old man led the way up flight after flight of stairs, till they arrived at the house-top. Seated on a carpet, and leaning against a chimney-stack, were two girls bending over books. Some humble creepers were trained round the chimney-pots, and evergreens were placed round the roof, and a few more books, a basket of gaily colored scraps, and bits of tinsel, and another of common print stuff lay near. One of the girls rose on seeing that Riah had brought a visitor, but the other remarked, “I’m the person of the house down-stairs, but I can’t get up, whoever you are, because my back is bad and my legs are queer.”

“This is my master,” said Riah, speaking to the two girls, “and this,” he added, turning to Mr. Fledgeby, “is Miss Jenny Wren; she lives in this house, and is a clever little dressmaker for little people. Her friend Lizzie,” continued Riah, introducing the second girl. “They are good girls, both, and as busy as they are good; in spare moments they come up here and take to book learning.”

“We are glad to come up here for rest, sir,” said Lizzie, with a grateful look at the old Jew. “No one can tell the rest what this place is to us.”

“Humph!” said Mr. Fledgeby, looking round, “Humph!” He was so much surprised that apparently he couldn’t get beyond that word, and as he went down again the old chimney-pots in their black cowls seemed to turn round and look after him as if they were saying “Humph” too.

Lizzie, the elder of these two girls, was strong and handsome, but little Jenny Wren, whom she so loved and protected, was small and deformed, though she had a beautiful little face, and the longest and loveliest golden hair in the world, which fell about her like a cloak of shining curls, as though to hide the poor little misshapen figure.

The hit single ‘Jenny Wren’ from Paul McCartney’s critically acclaimed 2005 album, Chaos and Creation in the Backyard. The solo at the end is played on a duduk, an Armenian woodwind instrument, by Pedro Eustache, an acknowledged master of World Music woodwinds, reeds and wind synthesizers. His collection of more than 600 instruments from all over the world include many he has created and built himself. For the McCartney session, he tuned the duduk down a step, creating a sound reminiscent of earlier McCartney acoustic-based classics such as ‘Blackbird’ and ‘Mother Nature’s Son.’

The Jew Riah, as well as Lizzie, was always kind and gentle to Jenny Wren, who called him her godfather. She had a father, who shared her poor little rooms, whom she called her child; for he was a bad, drunken, worthless old man, and the poor girl had to care for him, and earn money to keep them both. She suffered a great deal, for the poor little bent back always ached sadly, and was often weary from constant work but it was only on rare occasions, when alone or with her friend Lizzie, who often brought her work and sat in Jenny’s room, that the brave child ever complained of her hard lot. Sometimes the two girls–Jenny helping herself along with a crutch–would go and walk about the fashionable streets, in order to note how the grand folks were dressed. As they walked along, Jenny would tell her friend of the fancies she had when sitting alone at her work. “I imagine birds till I can hear them sing,” she said one day, “and flowers till I can smell them. And oh! the beautiful children that come to me in the early mornings! They are quite different to other children, not like me, never cold, or anxious, or tired, or hungry, never any pain; they come in numbers, in long bright slanting rows, all dressed in white, and with shiny heads. ‘Who is this in pain?’ they say, and they sweep around and about me, take me up in their arms, and I feel so light, and all the pain goes. I know when they are coming a long way off, by hearing them say, ‘Who is this in pain?’ and I answer, ‘Oh my blessed children, it’s poor me! have pity on me, and take me up and then the pain will go.”

Lizzie sat stroking and brushing the beautiful hair, whilst the tired little dressmaker leant against her when they were at home again, and as she kissed her good-night, a miserable old man stumbled into the room. “How’s my Jenny Wren, best of children?” he mumbled, as he shuffled unsteadily towards her, but Jenny pointed her small finger towards him, exclaiming-“Go along with you, you bad, wicked old child, you troublesome, wicked old thing, I know where you have been, I know your tricks and your manners.” The wretched man began to whimper like a scolded child. “Slave, slave, slave, from morning to night,” went on Jenny, still shaking her finger at him, “and all for this; ain’t you ashamed of yourself, you disgraceful boy?”

“Yes; my dear, yes,” stammered the tipsy old father, tumbling into a corner. Thus was the poor little dolls’ dressmaker dragged down day by day by the very hands that should have cared for and held her up; poor, poor little dolls’ dressmaker! One day when Jenny was on her way home with Riah, who had accompanied her on one of her walks to the West End, they came on a small crowd of people. A tipsy man had been knocked down and badly hurt. “Let us see what it is!” said Jenny, coming swiftly forward on her crutches. The next moment she exclaimed-“Oh, gentlemen-gentlemen, he is my child, he belongs to me, my poor, bad old child!”

Child-adult Jenny Wren Miss Wren, a dolls’ dressmaker, sits with the benevolent Riah in this wood engraving by Northumberland-born illustrator Thomas Dalziel done for the original monthly installment of Charles Dickens’s last completed novel Our Mutual Friend. Image courtesy The Victorian Web.

“Your child-belongs to you,” repeated the man who was about to lift the helpless figure on to a stretcher, which had been brought for the purpose. “Aye, it’s old Dolls-tipsy old Dolls,” cried someone in the crowd, for it was by this name that they knew the old man.

“He’s her father, sir,” said Riah in a low tone to the doctor who was now bending over the stretcher.

‘But nothing could make her life otherwise than a suffering one till the happy morning when her child-angels visited her for the last time and carried her away to the land where all such pain as hers is healed for evermore.’ Image from Dickens’ Dream Children, p. 242, a scene in Jenny Wren’s room in the neighborhood of St. Mary Axe, London. Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham, reproduced with permission from The Victorian Web.

“So much the worse,” answered the doctor, “for the man is dead.”

Yes, “Mr. Dolls” was dead, and many were the dresses which the weary fingers of the sorrowful little worker must make in order to pay for his humble funeral and buy a black frock for herself. Riah sat by her in her poor room, saying a word of comfort now and then, and Lizzie came and went, and did all manner of little things to help her; but often the tears rolled down on to her work. “My poor child,” she said to Riah, “my poor old child, and to think I scolded him so.”

“You were always a good, brave, patient girl,” returned Riah, smiling a little over her quaint fancy about her child, “always good and patient, however tired.”

And so the poor little “person of the house” was left alone but for the faithful affection of the kind Jew and her friend Lizzie. Her room grew pretty and comfortable, for she was in great request in her “profession,” as she called it, and there were now no one to spend and waste her earnings. But nothing could make her life otherwise than a suffering one till the happy morning when her child-angels visited her for the last time and carried her away to the land where all such pain as hers is healed for evermore.