Author of Hymn-Tunes and Their Story

A Charles Dickens Bicentennial Moment

(Editor’s note: Continuing the Bicentennial Dickens salute we began in the February issue of www.TheBluegrassSpecial.com, this month we remain focused on our subject’s relationship to music, both as a musician and as an author, as chronicled in James T. Lightwood’s 1912 study titled Charles Dickens And Music, originally published in London by Charles H. Kelly. This month, Chapter VII, Some Noted Singers.)

The kind-hearted Tom Pinch, from Dickens’s novel Martin Chuzzlewit, at the organ. ‘The references to the organ are both numerous and interesting, and it is pretty evident that this instrument had a great attraction for Dickens.’

CHAPTER VII

SOME NOTED SINGERS

The Micawbers

Dickens presents us with such an array of characters who reckon singing amongst their various accomplishments that it is difficult to know where to begin. Perhaps the marvelous talents of the Micawber family entitle them to first place. Mrs. Micawber was famous for her interpretation of ‘The Dashing White Sergeant’ and ‘Little Taffline’ when she lived at home with her papa and mamma, and it was her rendering of these songs that gained her a spouse, for, as Mr. Micawber told Copperfield,

when he heard her sing the first one, on the first occasion of his seeing her beneath the parental roof, she had attracted his attention in an extraordinary degree, but that when it came to ‘Little Tafflin,’ he had resolved to win that woman or perish in the attempt.

It will be remembered that Mr. Bucket (Bleak House) gained a wife by a similar display of vocal talent. After singing ‘Believe me, if all those endearing young charms,’ he informs his friend Mrs. Bagnet that this ballad was

his most powerful ally in moving the heart of Mrs. Bucket when a maiden, and inducing her to approach the altar. Mr. Bucket’s own words are ‘to come up to the scratch.’

Mrs. Micawber’s ‘Little Taffline’ was a song in Storace’s ballad opera Three and the Deuce, words by Prince Hoare. It will be interesting to see what the song which helped to mould Micawber’s fate was like.

LITTLE TAFFLINE.

There was also a character called Little Taffline in T. Dibdin’s St. David’s Day, the music for which was compiled and composed by Thomas Attwood, organist of St. Paul’s Cathedral.

Her other song, ‘The Dashing White Sergeant,’ was a martial and very popular setting of some words by General Burgoyne.

Micawber could both sing and hum, and when music failed him he fell back on quotations. As he was subject to extremes of depression and elevation it was nothing unusual for him to commence a Saturday evening in tears and finish up with singing ‘about Jack’s delight being his lovely Nan’ towards the end of it. Here we gather that one of his favourite songs was C. Dibdin’s ‘Lovely Nan,’ containing these two lines:

But oh, much sweeter than all these

Is Jack’s delight, his lovely Nan.

His musical powers made him useful at the club-room in the King’s Bench, where David discovered him leading the chorus of ‘Gee up, Dobbin.’ This would be ‘Mr. Doggett’s Comicall Song’ in the farce The Stage Coach, containing the lines—

With a hey gee up, gee up, hay ho;

With a hay gee, Dobbin, hey ho!

‘Auld Lang Syne’ was another of Mr. Micawber’s favourites, and when David joined the worthy pair in their lodgings at Canterbury they sang it with much energy. To use Micawber’s words—

When we came to ‘Here’s a hand, my trusty frere’ we all joined hands round the table; and when we declared we would ‘take a right gude willie waught,’ and hadn’t the least idea what it meant, we were really affected.

The memory of this joyous evening recurred to Mr. M. at a later date, after the feast in David’s rooms, and he calls to mind how they had sung

We twa had run about the braes

And pu’d the gowans fine.

He confesses his ignorance as to what gowans are,

but I have no doubt that Copperfield and myself would frequently have taken a pull at them, if it had been feasible

In the last letter he writes he makes a further quotation from the song. On another occasion, however, under the stress of adverse circumstances he finds consolation in a verse from ‘Scots, wha hae’,’ while at the end of the long epistle in which he disclosed the infamy of Uriah Heep, he claims to have it said of him, ‘as of a gallant and eminent naval Hero,’ that what he has done, he did

For England, home, and beauty.

‘The Death of Nelson,’ from which this line comes, had a long run of popularity. Braham, the composer, was one of the leading tenors of the day, and thus had the advantage of being able to introduce his own songs to the public. The novelist’s dictum that ‘composers can very seldom sing their own music or anybody else’s either’ (Pickwick Papers, 15) may be true in the main, but scarcely applies to Braham, who holds very high rank amongst English tenors. Another song which he wrote with the title ‘The Victory and Death of Lord Viscount Nelson’ met with no success. The one quoted by Micawber was naturally one of Captain Cuttle’s favourites, and it is also made use of by Silas Wegg.

The musical gifts of Mr. and Mrs. Micawber descended to their son Wilkins, who had ‘a remarkable head voice,’ but having failed to get into the cathedral choir at Canterbury, he had to take to singing in public-houses instead of in sacred edifices. His great song appears to have been ‘The Woodpecker Tapping.’ When the family emigrated Mr. M. expressed the hope that ‘the melody of my son will be acceptable at the galley fire’ on board ship. The final glimpse we get of him is at Port Middlebay, where he delights a large assembly by his rendering of ‘Non Nobis,’ and by his dancing with the fourth daughter of Mr. Mell.

The ‘Woodpecker’ song is referred to in an illustrative way by Mrs. Finching (Little Dorrit), who says that her papa

is sitting prosily breaking his new-laid egg in the back parlour like the woodpecker tapping.

Captain Cuttle

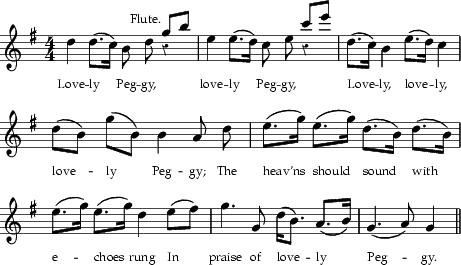

Captain Cuttle is almost as full of melody as Micawber, though his repertoire is chiefly confined to naval ditties. His great song is ‘Lovely Peg,’ and his admiration for Florence Dombey induces him to substitute her name in the song, though the best he can accomplish is ‘Lovely Fleg.’

There are at least three eighteenth-century ballads with Peg, or Lovely Peg, for the subject, and it is not certain which of these the Captain favoured. This is one of them:

Once more I’ll tune the vocal shell,

To Hills and Dales my passion tell,

A flame which time can never quell,

That burns for lovely Peggy.

Then comes this tuneful refrain:

The two others of this period that I have seen are called ‘Peggy’ and ‘Lovely Peggy, an imitation.’ However, it is most probable that the one that the Captain favoured—in spite of the mixture of names—was C. Dibdin’s ‘Lovely Polly.’

LOVELY POLLY

Dickens was very familiar with Dibdin’s songs, while the eighteenth-century ones referred to he probably never heard of, as they are very rarely found.

The worthy Captain enjoys a good rollicking song, preferably of a patriotic turn, but is very unreliable as to the sources of his ditties.

‘Wal’r, my boy,’ replied the Captain, ‘in the Proverbs of Solomon you will find the following words, “May we never want a friend in need, nor a bottle to give him!” When found, made a note of.’

This is taken from a song by J. Davy, known as ‘Since the first dawn of reason,’ and was sung by Incledon.

Since the first dawn of reason that beam’d on my mind,

And taught me how favoured by fortune my lot,

To share that good fortune I still am inclined,

And impart to who wanted what I wanted not.

It’s a maxim entitled to every one’s praise,

When a man feels distress, like a man to relieve him;

And my motto, though simple, means more than it says,

‘May we ne’er want a friend or a bottle to give him.’

He is equally unreliable as to the source of a still more famous song. When Florence Dombey goes to see him the Captain intimates his intention of standing by old Sol Gills,

‘and not desert until death do us part, and when the stormy winds do blow, do blow, do blow—overhaul the Catechism,’ said the Captain parenthetically, ‘and there you’ll find these expressions.’

I have not heard of any church that has found it necessary to include this old refrain in its Catechism, nor even to mix it up with the Wedding Service.

A further mixture of quotations occurs when he is talking of Florence on another occasion. Speaking of the supposed death of Walter he says,

Though lost to sight, to memory dear, and

England, home, and beauty.

The first part—which is one of Cuttle’s favourite quotations—is the first line of a song by G. Linley. He composed a large number of operas and songs, many of which were very popular. The second part of the quotation is from Braham’s ‘Death of Nelson.’

In conversation with his friend Bunsby, Cuttle says—

Give me the lad with the tarry trousers as shines to me like di’monds bright, for which you’ll overhaul the ‘Stanfell’s Budget,’ and when found make a note.

Elsewhere he mentions Fairburn’s ‘Comic Songster’ and the ‘Little Warbler’ as his song authorities.

The song referred to here is classed by Dr. Vaughan Williams amongst Essex folk-songs, but it is by no means confined to that county. It tells of a mother who wants her daughter to marry a tailor, and not wait for her sailor bold.

My mother wants me to wed with a tailor

And not give me my heart’s delight;

But give me the man with the tarry trousers,

That shines to me like diamonds bright.

After the firm of Dombey has decided to send Walter to Barbados, the boy discusses his prospects with his friend the Captain, and finally bursts into song—

How does that tune go that the sailors sing?

For the port of Barbados, Boys!

Cheerily!

Leaving old England behind us, boys!

Cheerily!

Here the Captain roared in chorus,

Oh cheerily, cheerily!

Oh cheer-i-ly!

All efforts to trace this song have failed, and for various reasons I am inclined to think that Dickens made up the lines to fit the occasion; while the words ‘Oh cheerily, cheerily’ are a variant of a refrain common in sea songs, and the Captain teaches Rob the Grinder to sing it at a later period of the story. The arguments against the existence of such a song are: first, that the Dombey firm have already decided to send the boy to Barbados, and as there is no song suitable, the novelist invents one; and in the second place there has never been a time in the history of Barbados to give rise to such a song as this, and no naval expedition of any consequence has ever been sent there. It is perhaps unnecessary to urge that there is no such place as the ‘Port of Barbados.’

Dick Swiveller

None of Dickens’ characters has such a wealth of poetical illustration at command as Mr. Richard Swiveller. He lights up the Brass office “with scraps of song and merriment,” and when he is taking Kit’s mother home in a depressed state after the trial he does his best to entertain her with “astonishing absurdities in the way of quotation from song and poem.” From the time of his introduction, when he ‘obliged the company with a few bars of an intensely dismal air,’ to when he expresses his gratitude to the Marchioness—

And she shall walk in silk attire,

And siller have to spare—

there is scarcely a scene in which he is present when he does not illumine his remarks by quotations of some kind or other, though there are certainly a few occasions when his listeners are not always able to appreciate their aptness. For instance in the scene between Swiveller and the single gentleman, after the latter has been aroused from his slumbers, and has intimated he is not to be disturbed again.

‘I beg your pardon,’ said Dick, halting in his passage to the door, which the lodger prepared to open, ‘when he who adores thee has left but the name—’

‘What do you mean?’

‘But the name,’ said Dick, ‘has left but the name—in case of letters or parcels—’

‘I never have any,’ said the lodger.

‘Or in case anybody should call.’

‘Nobody ever calls on me.’

‘If any mistake should arise from not having the name, don’t say it was my fault, sir,’ added Dick, still lingering; ‘oh, blame not the bard—’

‘I’ll blame nobody,’ said the lodger.

But that Mr. Swiveller’s knowledge of songs should be both ‘extensive and peculiar’ is only to be expected from one who held the distinguished office of ‘Perpetual Grand Master of the Glorious Apollers,’ although he seems to have been more in the habit of quoting extracts from them than of giving vocal illustrations. On one occasion, however, we find him associated with Mr. Chuckster ‘in a fragment of the popular duet of “All’s Well” with a long shake at the end.’

The following extract illustrates the “shake”:

ALL’S WELL (Duet).

Sung by Mr. Braham and Mr. Charles Braham.

Music by Mr. Braham.

Although most of Swiveller’s quotations are from songs, he does not always confine himself to them, as for instance, when he sticks his fork into a large carbuncular potato and reflects that “Man wants but little here below,” which seems to show that in his quieter moments he had studied Goldsmith’s Hermit.

Mr. Swiveller’s quotations are largely connected with his love-passages with Sophy Wackles, and they are so carefully and delicately graded that they practically cover the whole ground in the rise and decline of his affections. He begins by suggesting that “she’s all my fancy painted her.”

From this he passes to

She’s like the red, red rose,

That’s newly sprung in June.

She’s also like a melody,

That’s sweetly played in tune.

then

When the heart of a man is depressed with fears,

The mist is dispelled when Miss Wackles appears,

which is his own variant of

If the heart of a man is depressed with care,

The mist is dispelled when a woman appears.

But at the party given by the Wackleses Dick finds he is cut out by Mr. Cheggs, and so makes his escape saying, as he goes—

My boat is on the shore, and my bark is on the sea; but before I pass this door, I will say farewell to thee, and he subsequently adds—

Miss Wackles, I believed you true, and I was blessed in so believing; but now I mourn that e’er I knew a girl so fair, yet so deceiving.

The dénouement occurs some time after, when, in the course of an interview with Quilp, he takes from his pocket a small and very greasy parcel, slowly unfolding it, and displaying a little slab of plum cake, extremely indigestible in appearance and bordered with a paste of sugar an inch and a half deep.

‘What should you say this was?’ demanded Mr. Swiveller.

‘It looks like bride-cake,’ replied the dwarf, grinning.

‘And whose should you say it was?’ inquired Mr. Swiveller, rubbing the pastry against his nose with dreadful calmness. ‘Whose?’

‘Not—’

‘Yes,’ said Dick, ‘the same. You needn’t mention her name. There’s no such name now. Her name is Cheggs now, Sophy Cheggs. Yet loved I as man never loved that hadn’t wooden legs, and my heart, my heart is breaking for the love of Sophy Cheggs.’

With this extemporary adaptation of a popular ballad to the distressing circumstances of his own case, Mr. Swiveller folded up the parcel again, beat it very flat upon the palms of his hands, thrust it into his breast, buttoned his coat over it, and folded his arms upon the whole.

And then he signifies his grief by pinning a piece of crape on his hat, saying as he did so,

‘Twas ever thus: from childhood’s hour

I’ve seen my fondest hopes decay;

I never loved a tree or flower

But ’twas the first to fade away;

I never nursed a dear gazelle,

To glad me with its soft black eye,

But when it came to know me well,

s And love me, it was sure to marry a market gardener.

He is full of song when entertaining the Marchioness. ‘Do they often go where glory waits ’em?’ he asks, on hearing that Sampson and Sally Brass have gone out for the evening. He accepts the statement that Miss Brass thinks him a ‘funny chap’ by affirming that ‘Old King Cole was a merry old soul’; and on taking his leave of the little slavey he says,

‘Good night, Marchioness. Fare thee well, and if for ever then for ever fare thee well—and put up the chain, Marchioness, in case of accidents.

Since life like a river is flowing,

I care not how fast it rolls on, ma’am,

While such purl on the bank still is growing,

And such eyes light the waves as they run.’

On a later occasion, after enjoying some games of cards he retires to rest in a deeply contemplative mood.

‘These rubbers,’ said Mr. Swiveller, putting on his nightcap in exactly the same style as he wore his hat, ‘remind me of the matrimonial fireside. Cheggs’s wife plays cribbage; all-fours likewise. She rings the changes on ’em now. From sport to sport they hurry her, to banish her regrets; and when they win a smile from her they think that she forgets—but she don’t.’

Many of Mr. Swiveller’s quotations are from Moore’s Irish Melodies, though he has certainly omitted one which, coming from him, would not have been out of place, viz. ‘The time I’ve lost in wooing’!

On another occasion Swiveller recalls some well-known lines when talking to Kit. ‘An excellent woman, that mother of yours, Christopher,’ said Mr. Swiveller; ‘“Who ran to catch me when I fell, and kissed the place to make it well? My mother.”’

This is from Ann Taylor’s nursery song, which has probably been more parodied than any other poem in existence. There is a French version by Madame à Taslie, and it has most likely been translated into other languages.

Dick gives us another touching reference to his mother. He is overcome with curiosity to know in what part of the Brass establishment the Marchioness has her abode.

My mother must have been a very inquisitive woman; I have no doubt I’m marked with a note of interrogation somewhere. My feelings I smother, but thou hast been the cause of this anguish, my—

This last remark is a memory of T.H. Bayly’s celebrated song ‘We met,’ which tells in somewhat incoherent language the story of a maiden who left her true love at the command of her mother, and married for money.

The world may think me gay,

For my feelings I smother;

Oh thou hast been the cause

Of this anguish—my mother.

T. Haynes Bayly was a prominent song-writer some seventy years ago (1797–1839). His most popular ballad was ‘I’d be a Butterfly.’ It came out with a coloured title-page, and at once became the rage, in fact, as John Hullah said, ‘half musical England was smitten with an overpowering, resistless rage for metempsychosis.’ There were many imitations, such as ‘I’d be a Nightingale’ and ‘I’d be an Antelope.’

Teachers and Composers

Although we read so much about singers, the singing-master is rarely introduced, in fact Mr. M’Choakumchild (H.T.), who ‘could teach everything from vocal music to general cosmography,’ almost stands alone. However, in view of the complaints of certain adjudicators about the facial distortions they beheld at musical competitions, it may be well to record Mrs. General’s recipe for giving ‘a pretty form to the lips’ (Little Dorrit).

Papa, potatoes, poultry, prunes, and prism are all very good words for the lips, especially prunes and prism. You will find it serviceable in the formation of a demeanour.

Nor do composers receive much attention, but amongst the characters we may mention Mr. Skimpole (Bleak House), who composed half an opera, and the lamp porter at Mugby Junction, who composed ‘Little comic songs-like.’ In this category we can scarcely include Mrs. Kenwigs, who ‘invented and composed’ her eldest daughter’s name, the result being ‘Morleena.’ Mr. Skimpole, however, has a further claim upon our attention, as he ‘played what he composed with taste,’ and was also a performer on the violoncello. He had his lighter moments, too, as when he went to the piano one evening at 11 p.m. and rattled hilariously

That the best of all ways to lengthen our days

Was to steal a few hours from Night, my dear!

It is evident that his song was ‘The Young May Moon,’ one of Moore’s Irish Melodies.

The young May moon is beaming, love,

The glow-worm’s lamp is gleaming, love,

How sweet to rove

Through Morna’s grove

While the drowsy world is dreaming, love!

Then awake—the heavens look bright, my dear!

‘Tis never too late for delight, my dear!

And the best of all ways

To lengthen our days

Is to steal a few hours from the night, my dear!

Silas Wegg’s Effusions

We first meet Silas Wegg in the fifth chapter of Our Mutual Friend, where he is introduced to us as a ballad-monger. His intercourse with his employer, Mr. Boffin, is a frequent cause of his dropping into poetry, and most of his efforts are adaptations of popular songs. His character is not one that arouses any sympathetic enthusiasm, and probably no one is sorry when towards the end of the story Sloppy seizes hold of the mean little creature, carries him out of the house, and deposits him in a scavenger’s cart ‘with a prodigious splash.’

The following are Wegg’s poetical effusions, with their sources and original forms.

Book I, Ch. 5.

‘Beside that cottage door, Mr. Boffin,’ from ‘The Soldier’s Tear’ (Alexander Lee)

Beside that cottage porch

A girl was on her knees;

She held aloft a snowy scarf

Which fluttered in the breeze.

She breath’d a prayer for him,

A prayer he could not hear;

But he paused to bless her as she knelt,

And wip’d away a tear.

Book I, Ch. 15.

The gay, the gay and festive scene,

I’ll tell thee how the maiden wept, Mrs. Boffin.

From ‘The Light Guitar.’

Book I, Ch. 15.

‘Thrown on the wide world, doomed to wander and roam.’ From ‘The Peasant Boy’ (J. Parry)

Thrown on the wide world, doom’d to wander and roam,

Bereft of his parents, bereft of his home,

A stranger to pleasure, to comfort and joy,

Behold little Edmund, the poor Peasant Boy.

Book I, Ch. 15.

‘Weep for the hour.’ From ‘Eveleen’s Bower’ (T. Moore)

Oh! weep for the hour

When to Eveleen’s bower

The lord of the valley with false vows came.

Book I, Ch. 15.

‘Then farewell, my trim-built wherry.’ From ‘The Waterman’ (C. Dibdin)

Book II, Ch. 7.

‘Helm a-weather, now lay her close.’ From ‘The Tar for all Weathers’ (Unknown)

Book III, Ch. 6.

‘No malice to dread, sir.’ From verse 3 of ‘My Ain Fireside.’ (Words by Mrs. E. Hamilton)

Nae falsehood to dread, nae malice to fear,

But truth to delight me, and kindness to cheer;

O’ a’ roads to pleasure that ever were tried,

There’s nane half so sure as one’s own fireside.

My ain fireside, my ain fireside,

Oh sweet is the blink o’ my ain fireside.

Book III, Ch. 6.

And you needn’t, Mr. Venus, be your black bottle,

For surely I’ll be mine,

And we’ll take a glass with a slice of lemon in it, to which you’re partial,

For auld lang syne.

A much altered version of verse 5 of Burns’ celebrated song.

Book III, Ch. 6.

Charge, Chester, charge,

On Mr. Venus, on.

From Scott’s Marmion.

Book IV, Ch. 3.

‘If you’ll come to the bower I’ve shaded for you.’ From ‘Will you Come to the Bower’ (T. Moore)

Will you come to the Bower I’ve shaded for you,

Our bed shall be roses, all spangled with dew.

Will you, will you, will you, will you come to the Bower?

Will you, will you, will you, will you come to the Bower?

Next Month: Chapter VIII