Charles Ives’s home in Redding, CT (photo: Zoë Martlew)

On August 6 the iconoclastic author-novelist-broadcaster-cultural commentator Norman Lebrecht reported in his Slipped Disc blog of developers’ plans to raze the Redding, CT, house where composer Charles Ives lived and worked. The Charles Ives Society attempted to raise funds to buy the house from the composer’s grandson, Charles Ives Tyler, for preservation as a museum, but the effort failed. According to a recent report from Lebrecht, Tyler has accepted “a substantial offer” from another buyer, all but assuring the house’s destruction.

The Ives Society has issued the following comment:

The Ives Society is disappointed to have been notified by the seller that he has accepted a cash offer for the Ives Homestead.

We will update information on ongoing preservation efforts as it comes in. Contributions to the Ives Society for its efforts to preserve the legacy of Charles Ives can be sent to The Charles Ives Society, Granoff Music Center, Tufts University, 20 Talbot Avenue, Medford, MA 02155.

The real‐estate agent, handling the sale, who is an expert on historical buildings in the area and sympathetic to the Ives cause, said property investors were eager to get their hands on this prime bit of real estate and had no interest in its historical significance.

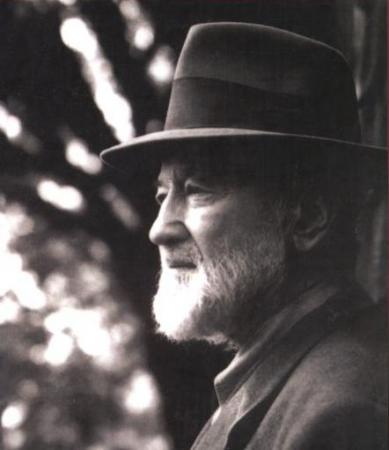

Charles Ives

In a note to Norman Lebrecht, cellist and performance artist Zoë Martlew wrote of her visit to the Ives house:

Charles Ives’ country house is hidden away amidst verdant rolling hills of unspoilt New England countryside. Chipmunks and gophers scuttle in the surrounding forest and the fragrant air is filled with dragonflies, humming birds and the sound of leaves fanned by the wind.

It would seem that time has stood still since Ives bought this land in Redding, Connecticut. He had a house and barn built in 1912 and moved in with his wife Harmony a year later. It was to become their country home until his death in 1954 and has been lived in by the Ives family ever since.

Until now.

Among the many comments to this news appearing at the end of Lebrecht’s latest report was this from Nikola Ragusa, who was involved in a fundraising effort to save the Ives house:

“There were two groups trying to make this happen, me being one of them. But frankly there were not enough people interested in saving it. Or rather not that many willing to donate but thought it was a good cause. Now I can’t say how well the Ives Society did on raising funds, but on my side of things I worked long, long hours to crowdsource to buy this house via Indiegogo for a few weeks. It’s sad to see the online world not knowing that much about Ives, but giving Amanda Palmer a million dollars. At least we tried to save this house and do something very cool with it. Thanks to the people who tried to raise awareness about the house. Cheers!”

FYI: This house is not to be confused with the Charles Ives Birthplace Museum in Danbury, CT.

In 1906 Ives composed “The Unanswered Question” (originally titled “A Contemplation of a Serious Matter or The Perennial Unanswered Question) and “Central Park in the Dark” (originally titled “A Contemplation of Nothing Serious or Central Park in the Dark”) under the title “Two Compositions.” In his 1973 Norton Lectures, which took their title from “The Unanswered Question,” Leonard Bernstein posited that the woodwinds represent our human answers growing increasingly impatient and desperate, until they lose their meaning entirely.

Charles Ives, ‘The Unanswered Question.’ Leonard Bernstein and the New York Philharmonic. In his notes Ives described the work as a ‘cosmic landscape’ in which the strings represent ‘the Silences of the Druids—who Know, See and Hear Nothing.’ The trumpet then asks ‘The Perennial Question of Existence’ and the woodwinds seek ‘The Invisible Answer,’ but abandon it in frustration, so that ultimately the question is answered only by the ‘Silences.’

Charles Ives, ‘Central Park in the Dark,’ Lawrence Foster conducting the BBC Symphony Orchestra. Ives described his composition as ‘a picture-in-sounds of the sounds of nature and of happenings that men would hear some thirty or so years ago (before the combustion engine and radio monopolized the earth and air), when sitting on a bench in Central Park on a hot summer night.’