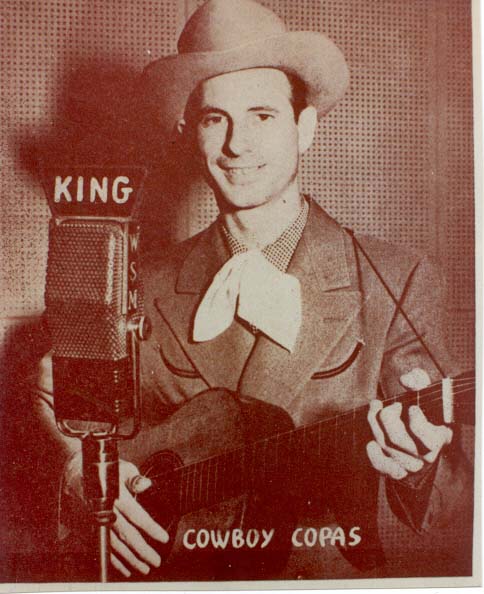

It is the misfortune of Lloyd Estel Copas to be better remembered for how and with whom he died than for the wonderful music he made as Cowboy Copas, in which guise he was a dominant presence on the country charts from 1946 to 1951 after signing with Syd Nathan’s King label, and gained a second life following a latent period when he rebounded on Don Pierce’s Starday label in 1961 with a chart-topping classic, “Alabam,” the inaugural entry in a productive two-year run dashed by tragedy.

Generations that might otherwise have completely forgotten him now know Cowboy as one of four occupants in a small Piper Comanche aircraft piloted by Cowboy’s son-in-law Randy Hughes, who crashed into a hillside near Camden, Tennessee, on March 5, 1963. Killed along with the then-50-year-old Cowboy and Hughes were Cowboy’s good friend and budding icon Patsy Cline, and another country star of the day, Hawkshaw Hawkins. Ironically, they were returning from a benefit in Kansas City for the family of DJ Cactus Jack Call, who had been killed in a car accident. That was the last but not the only irony of Cowboy’s life. In 1950 a Grand Ole Opry publicist asserted that Copas had grown up on his father’s ranch near Muskogee, Oklahoma; in fact, he was born July 15, 1913 on Moon Hollow near Blue Creek in Adams County, Ohio. Many years later he became known variously as “Cowboy” Copas and the “Oklahoma Cowboy.”

Cowboy Copas and Patsy Cline duet on ‘I’m Hog Tied Over You’ on Jubilee USA in June 1960, with host Eddy Arnold.

Cowboy Copas on The Grand Ole Opry Show performing ‘Filipino Baby,’ his career launching #4 hit from 1946

Adopted nicknames notwithstanding, Cowboy never considered himself a western (or cowboy) singer. He did possess, however, a sturdy low tenor voice with a timbre reminiscent at times of two great western singers of his day, Gene Autry and Roy Rogers (more the latter than the former). He didn’t have either Autry’s or Rogers’s rhythmic sense; rather, he phrased in a more formal style, clearly articulating his lyrics, always in control, his country leanings evident only in the slight southern drawl he affected periodically—Billy Eckstine might be more the Copas role model, or the Mills Brothers, and the deepest roots of his approach can be traced all the way back to 1800s barbershop vocalizing, which in turn was beholden to Italian bel canto singing with its graceful phrasing, impeccable breath control and unadorned attack.

Cowboy Copas, ‘Signed, Sealed and Delivered.’ the followup to ‘Filipino Baby’ charted higher than its predecessor at #2 country.

Copas’s professional path is as direct as his singing. At age 14 he was performing on Cincinnati radio stations WLW-AM and WKRC-AM; in 1940 he relocated to Knoxville, TN, and with his band the Gold Star Rangers performed on WNOX-AM; in 1944 his big break came when, while part of the roster of WLW’s Boone County Jamboree show, he signed with Syd Nathan’s fledgling King label and made his first recordings. Out of that came his first single, “Filipino Baby,” but the pressing was of such low quality that Nathan built his own manufacturing plant and had Copas recut some of the songs from the ’44 session, including “Filipino Baby,” which was issued in 1945 and became a country smash, peaking at #4 on the chart in ’46—the same year he briefly replaced Eddy Arnold as the vocalist in Pee Wee King’s band and made his Grand Ole Opry debut. Copas’s “Filipino Baby” was a variation of an 1898 song written by Charles K. Harris called “Ma Filipino Babe” (Harris also wrote “After the Ball,” one of the signature songs of his time—“the era’s quintessential tearjerker,” as Colin Escott remarks in his liner notes to this double-disc reissue of Copas’s King and Starday singles). The Harris song’s overtly racist overtones were subsequently smoothed over in Bill Cox’s 1937 version, from which Copas took his cue in addition to adding some sweet-natured fillips of his own.

After “Filipino Baby” it was off to the races for Cowboy: between ’46 and ’52 he placed 10 singles in the Top 20, and of those nine peaked in the Top 10. Whereas some of these bear Copas’s name as writer or co-writer, Escott reminds us that artists buying songs from struggling writers (especially backstage at the Opry) was common practice back then, and the presence of Syd Nathan’s wife Lois Mann as a co-writer on many of the tunes (fronting for her husband’s co-publishing interest in the song) hints that many of the so-called Copas originals came from other’s pens. One of those Copas-Mann songs, 1948’s “Signed, Sealed and Delivered,” was an even bigger hit than “Filipino Baby,” rising to #2 on the chart and far more a heart-tugger: it’s about the devastation of a broken heart as sung to the woman who done him wrong, and overflows with tears, in Copas’s plaintive delivery and in the weeping fiddle and pedal steel accompaniment (there’s also a trilling mandolin deep in the mix to enhance the lonely mood). Cowboy’s most beautiful recording followed, a genuine American classic in “Tennessee Waltz,” a Pee Wee King song its writer was willing to sell for $50 only to be turned down by Syd Nathan, who told Copas, “Ain’t no song in the world worth that.” Well… Copas recorded it first, a warm treatment that went to #3; King’s recording followed; but it two years later, in 1950, when “Tennessee Waltz” entered the American canon on the strength of Patti Page making it her own (her single remained atop the charts for 13 weeks), thanks to Page turning it into an incomparably wounded torch song, as beautiful as it was sad. But Cowboy had a gift too when it came to heartbreak and sentimental songs, one of the finest of the latter being Mac Wiseman’s bluegrass-tinged ballad “’Tis Sweet To Be Remembered,” a #8 hit in 1952; from the Starday years, the supposedly Copas-penned ballad “True Love Is the Greatest Thing,” which in its pop styled female backing chorus reflects an embrace of the nascent Nashville Sound, elicits a fine, sincere Copas vocal, almost spiritual in its praise of the topic at hand.

Patti Page’s epic ‘Tennessee Waltz,’ first recorded by Cowboy Copas in 1948, when it became a #3 country single for him, his third straight hit since signing with the King label.

Copas left King on a high note, with Top 10 hits on George Morgan’s “Candy Kisses” (#5), Eddy Howard’s mystical story-song “The Strange Little Girl” (#5) and the abovementioned “’Tis Sweet To Be Remembered” (#8), strong performances all, but covers of other artists’ bubbling-under hits. Wandering label-less for two years, he signed with Dot, where Mac Wiseman became his producer. Rock ‘n’ roll had now taken hold, some country labels were running scared, and others were trying to cash in, Dot being among the latter. In an effort to recast Cowboy as a rocker, Dot not only billed him as Lloyd Copas, so as to not alienate his country fans, but introduced him in his new guise with a tune penned by Herb Alpert and Lou Adler, “Circle Rock,” a credible rockabilly-influenced bopper featuring some rousing piano work by Hargus “Pig” Robbins; its flip side, “(Won’t You Ride) In My Little Red Wagon,” is arguably the more intense of the two cuts, especially the wild-assed guitar solo during the break. It may have seemed an outlandish idea, turning Cowboy Copas into a rock ‘n’ roll idol, but he had demonstrated in his career an affinity for the big beat in his uptempo country tunes. As seen below, a rare 1962 clip shows Cowboy pretty well tearing it up on a medley of three of his Starday hits.

From 1962, Cowboy offers a spirited medley of ‘Flat Top’ (the followup to ‘Alabam’ peaked at #9 country), ‘Alabam’ and ‘Sunny Tennessee,’ the #12 followup to ‘Flat Top.’

Cowboy Copas (billed as Lloyd Copas), ‘Circle Rock,’ written by Herb Alpert and Lou Adler, with Hargus ‘Pig’ Robbins on piano and Buddy Harman on drums in the Dot label’s failed effort at breaking Copas as a rock ‘n’ roll artist (1958).

Lloyd Copas, ‘(Won’t You Ride In) My Little Red Wagon,’ the flip side of ‘Circle Rock.’ Check out the wild rock ‘n’ roll guitar solo during the break.

Apart from “Tennessee Waltz,” Copas’s lasting contribution to the country canon came during his Starday years, which begat a remarkable comeback from a near-eight-year chart drought when it seemed like the times had overtaken Cowboy. “Alabam,” a song Copas reworked from a 1927 Frank Hutchinson recording called “Coney Isle,” giving it a more pronounced shuffle, obviously changing the locale to the Heart of Dixie (in retooling Hutchinson’s lyrics Cowboy would seem to have stepped in it by characterizing the good folks in the Yellowhammer State as being content with “eatin’ up their chicken and drinkin’ their wine,” not to mention the reference to multiple thieving tramps all around, but no one seems to have objected) and transplanting the good vibes of Coney Isle to the southland, to the tune of a #1 single, the only chart topper of Cowboy’s career but one for the ages.

Frank Hutchinson’s 1927 recording of ‘Coney Isle,’ the model for Cowboy Copas’s country classic, ‘Alabam,’ a #1 single in 1960

On The Grand Ole Opry Show, Cowboy Copas offers a live version of his #1 single of 1960, ‘Alabam.’

The Starday era ended for Cowboy posthumously in 1963 with “Goodbye Kisses,” a lush, poignant ballad rushed out by the label in the aftermath of his passing. A co-write with Lefty Frizzell, the single deserved better than its #12 peak position, but its broken-hearted melody, its theme of a permanent parting and the eerie echo on Cowboy’s vocal may have been a bit too morbid even for the country audience. Cowboy’s legacy soon faded as Patsy Cline gained posthumous recognition and influence—and record sales, continuing to the present day—beyond anything she had experienced in her lifetime. Here’s a tip of the Stetson to Cowboy Copas, though, for the memorable music he made and the honest effort he gave it, and to Real Gone Music for seeing the value in paying attention to this good man’s work.

Cowboy Copas’s posthumous hit, ‘Goodbye Kisses,” #12 1963, on Starday.