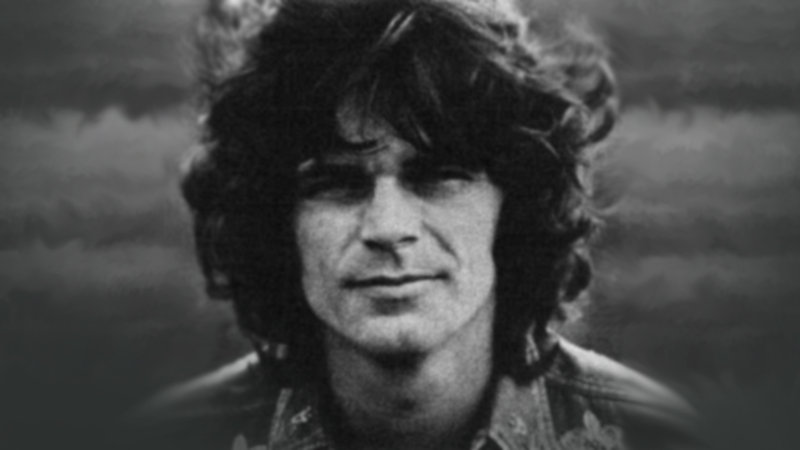

Vintage B.J. Thomas, captured in all his glory on The Complete Scepter Singles

THE COMPLETE SCEPTER SINGLES

B.J. Thomas

Real Gone Music

For those of a certain generation, the radio of their youth never seemed to be long without a new, great B.J. Thomas single. Indeed, between 1966 and 1972 he had 19 charting singles, some way bigger than others, some more regional than national hits, all of them choice, bedrock American pop informed by country and traditional rock ‘n’ roll, as you might expect from a singer born in Oklahoma and reared in Texas. Of course the song that made him a household name—no longer the exclusive province of the younger generation–was his soulful, easygoing reading of Bacharach-David’s “Raindrops Keep Fallin’ On My Head” as heard in the box office smash Butch Cassidy & the Sundance Kid. (The single was actually a re-recording of the version heard on the original soundtrack and on screen accompanying the famous bicycle riding scene.) Hal David’s passing on September 1 has generated more airplay for “Raindrops,” and more mentions of B.J.’s name, than has been heard in years. Losing a craftsman and poet of David’s order is always a blow, but B.J. is still very much with us (he recently released a well-considered album of Brazilian music, Once I Loved) and still persuasive in front of a mic. “Raindrops,” however, is a much-needed reminder of how formidable an artist was Thomas in his younger years, and to press the point a double-disc CD from Real Gone Music, The Complete Scepter Singles, provides compelling testimony of Thomas’s vocal brilliance before and après le deluge of “Raindrops.” To those who might have underrated the artist back in the day, here’s reason to reconsider your position; or if you’re too young to remember B.J.’s glory days, lament yet another stellar artist of yore whose gifts so outshine those of today’s pop stars. (Anyone see the laughable profile of Justin Bieber in The New Yorker recently? In which the writer tried to posit the auto-tuned teen heartthrob as a blue-eyed soul singer? The mind reels.)

B.J. Thomas, his career launching hit from 1966, ‘I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry,’ written by Hank Williams

B.J. was one of many ‘60s artists whose next record I awaited with almost as much anticipation as I did Dusty Springfield’s. Within that lusty, masculine tenor of his was a man in touch with his vulnerable and sensitive sides and unafraid to incorporate those feelings and fears into his interpretative readings, in the process transforming their sentiments into poetry of the heart. This Scepter set, chronologically sequenced, begins with his deeply felt take on Hank Williams’s “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry,” his #8 breakout hit from 1966. Though he had plenty of country in him. B.J. found a new way into Hank’s heartbreak classic, via an arrangement suffused with horns and B3 hums—a soul arrangement, pure and simple, simmering and epically sad, with the singer nonpareil working some magic on the lyrics via his artfully nuanced phrasing, knowing when to raise the intensity a smidgen or when to lay back and let the sorrow wash over him–until the end, when the horns rise, and rise again, and he leans into the phrase “I could cry-eye, I could cry-e-eye,” again and again, until, yes, we share in his inconsolable pain. A magnificent record, it was but the first of many more such moments over the next six years.

An early B.J. Thomas single cut for Houston’s Pacemaker label, ‘I Don’t Have a Mind of My Own,’ written by B.J.’s songwriting buddy Mark Charron, who supplied Thomas with the bulk of his material in the early days. Also included is the single’s B side, ‘Bring Back the Time,’ another Mark Charron song. The record was produced by the infamous Huey Meaux.

Raised just outside of Houston, B.J. started out singing lead in his big brother’s band The Triumphs in 1958 (recruited against his will, by the way); eventually the band was discovered by local record producers Charlie Booth and nascent legend Huey Meaux (the “Crazy Cajun” who produced the Sir Douglas Quintet and would later score big with Freddy Fender and Barbara Lynn before deep-sixing his career in a swamp of serious crimes ranging from sexual assault of a child, to drug possession, to child pornography, and then jumping bail and fleeing to Mexico). Soon enough the band was renamed B.J. Thomas & The Triumphs and commenced recording an album for Houston’s Pacemaker label. For original material it leaned largely on songs supplied by B.J.’s songwriting buddy Mark Charron. “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry” was first issued as the B side of a Charron-penned A side, “Hey Judy”; the single topped the local chart, and a friendly promoter named Steve Tyrell persuaded New York’s Scepter label (where Bacharach and David were then turning out magnificent pop monuments with Dionne Warwick) to pick up both the single and the band. In those early days B.J. and company were heavily reliant on Charron’s songs, and a few were mid-level charters. These were fairly standard pop-influenced rock ‘n’ roll, some being ebullient stompers such as the delightful, horn-infused “Wendy”; some being more adventurous structurally, such as “I Don’t Have a Mind of My Own,” with its shifting textures, silky soul sister background chorus, bright blasts of horns, atmospheric flourishes courtesy a tinkling xylophone (plus a hesitant two-chord opening phrase that seems inspired by the arrangement of “Down In the Boondocks,” a Joe South-penned tune that had been a hit a year earlier for Billy Joe Royal, another pretty good B.J. on the scene then). Apart from Charron’s songs, B.J. did a bang-up job with other covers: he transforms “Tomorrow Never Comes” from its origins as a sprightly Ernest Tubb-Johnny Bond western swing ditty taking issue with a faithless lover into a dramatic, Roy Orbison-style operetta with all the bruising and resentment the lyrics describe building inexorably to an emotional explosion at the end, with B.J.’s voice bursting into the stratosphere and the foreboding drums pounding apocalyptically behind him. Charron went toe-to-toe with Ernest and Johnny on his own “Walkin’ Back,” a non-hit 1967 single centered thematically on the emptiness of fame absent familial or romantic love. Beginning with a snippet of melody from the Shirelles’ (another Scepter act) “Will You Still Love Me Tomorrow” and changing “tonight you’re mine” to “tonight’s the night…” before charting its own course, the song is delivered from deep inside a soul hollowed out for lack of affection from those who mean most to him, but to whom he’s returning, seeking reconnection and revival.

‘Eyes of a New York Woman,’ written by Mark James. One of B.J.’s greatest Scepter singles. (1968)

Reading the story of B.J.’s career arc as described in Mike Ragogna’s liner notes, one cannot help but be struck by how the artist always seemed to be in the right place at the right time to make fruitful career connections. He went a long way with Charron’s fine songs, but when he looked outside his friend’s bailiwick, he found up-and-coming young songwriter Mark James, who gave him several top-notch singles, including his intense, organ-driven rock ‘n’ roll hit from 1968, “The Eyes of a New York Woman,” one of B.J.’s finest performances, delivering every ounce of joy a Gotham gal’s love has given him, along with an energizing optimism over the union’s long term prospects; this rousing celebration is set to a steadily intensifying rhythm, with starry-eyed lyrics (“lips as sweet as honeycomb/love that waits for me alone”), lovely washes of strings, captivating dynamics and a fully committed lead vocal in which Thomas’s expressive gift is vividly on display. He found Mark James upon setting up shop in Memphis, at Chips Moman’s American Studios. where he was renewed artistically by the support of Reggie Young and Tommy Cogbill on guitars and Bobby Emmons and Gene Crisman on drums, among others. One of his finest soul-searching ballads came out of this association, “I May Never Get to Heaven,” a wrenching, string-drenched song informed by lost love in which the singer mourns not what he no longer has but accepts, with a grace approaching the spiritual, that “I may never get to Heaven, but I didn’t miss it by much.” The next single was the infectious love song “Hooked On a Feeling,” a #5 hit in 1968 with its impossibly catchy chorus, sitar punctuations and insistent beat behind a triumphant B.J. vocal, another that should be counted among his high-water marks in the studio.

A strong segment from B.J.’s show at the Grand Palace in Branson, Missouri, begins with ‘Raindrops Keep Fallin’ On My Head’

Disc 2 charts yet another fortuitous association for B.J., namely when he got the shot at singing “Raindrops Keeping Fallin’ On My Head” for Butch Cassidy & The Sundance Kid, even though Burt Bacharach had intended to pitch the song to Bob Dylan (can you imagine?). Promo man Steve Tyrell again came into the picture, along with another Scepter executive, who together were promoting B.J. to a reluctant Bacharach and David; “Raindrops” finally came B.J.’s way when Ray Stevens turned it down. Needless to say, he made the most of his opportunity. A lesser known Bacharach-David-penned B.J. single is here, retrieved from obscurity even though it was a #26 hit in 1970. That would be “Everybody’s Out of Town,” the title track of an ensuing album and a true oddity in the Thomas catalogue in that it was a Bacharach-David art song, complete with a burping tuba, a rustic banjo, soothing strings, a muted trumpet, a ukulele and lyrics seemingly foretelling the collapse of society; that same year B&D delivered a sister song to “Everybody’s Out of Town” with “Send My Picture to Scranton, PA” (again the tuba!)” a most genial but decidedly unsentimental kissoff to a burg that had discarded him and now wants to embrace him in his success. The followup to “Raindrops” was a gospel-based love ballad, “Never Had It So Good,” a powerhouse love song from Ashford & Simpson that B.J. sells with all his might, as if those soaring choruses had been specially crafted for him—he eats it up. His big hit (#9) from 1970, the sensuous “I Just Can’t Help Believing,” a pop-country confection with horns and a beautifully modulated vocal, came from Brill Building giants Barry Mann & Cynthia Weil, who by that time had already writ their name large in pop history with their songs for Phil Spector’s artists.

B.J. Thomas, ‘Rock and Roll Lullabye,’ written by Barry Mann and Cynthia Weil, tackled a real-life issue non-judgmentally and with empathy that Thomas honored in his tender rendering. The single was a #15 hit for the artist in 1972 and signaled the end of his successful six-year tenure with Scepter Records.

Following a falling out with American Studios owner/producer Chips Moman, B.J. headed east, to Atlanta and the studio of producer Buddy Buie (who had steered the Classics IV’s great singles) and the musicians who would later comprise the Atlanta Rhythm Section. He cut some fine tunes co-written by Buie and Don Nix, but the high point of this association—and the end of his Scepter tenure, as the label was collapsing—was his Billy Joe Thomas album, released in 1972. This featured B.J. accompanied on each track by the artists who had written the songs. The finest of these many fine tunes was the touching “Rock and Roll Lullabye,” another Mann-Weil gem with a beautiful arrangement spiced with a delicate electric piano solo, twangy guitar, lush Beach Boys harmonies and a gentle B.J. vocal sensitively rendering the story of the offspring of a 16-year-old unwed mother (“my mama child”) recalling how his mother did her level best to make a good home for her child, assuring him in her rock and roll lullabye “that things would be all right.” It could have been maudlin, it could have been sickly sentimental, but in the Mann-Weil hands it was credible and moving, a real-life issue handled empathetically and non-judgmentally in the writing and in B.J.’s tender rendering. A #15 hit, “Rock and Roll Lullabye” stands for all intents and purposes as Thomas’s Scepter sayonara. He couldn’t have gone out on a note richer than this in humanity, musicality, agape or pure soul.

B.J. Thomas, ‘Hooked on a Feeling’,” a #5 hit in 1968 with its impossibly catchy chorus, sitar punctuations and insistent beat behind a triumphant B.J. vocal, another that should be counted among his high-water marks in the studio.

Lest we forget, Elvis and B.J. have an odd symmetry going for them. The King latched onto songwriter Mark James after hearing what he wrote for B.J. and soon had a #1 hit in England with “It’s Only Love,” which had peaked at #45 Stateside for Thomas. Thereafter Elvis dipped into the James catalogue for “Suspicious Minds,” “Raised on Rock,” “Always On My Mind” (yes, Elvis cut it first) and “Moody Blue,” among his finest latter-years recordings. At American Studios, and with Chips Moman and his crew, Elvis made his extraordinary comeback albums after his ’68 TV special. And “I Just Can’t Help Believing” inspired a great Elvis vocal and was one of his concert standards in the ‘70s. What we hear on The Complete Scepter Singles is an artist who had more than a casual connection to Presley. B.J. Thomas could and did sing it all back in these days (save for gospel, which he eventually got to). His versatility, his command of pop, country and blues idioms, his dramatic phrasing and vocal colors were very nearly on a par with Elvis’s, although Elvis had a considerable edge as a blues singer. Never a cultural icon, Thomas kept on making good, and sometimes great, records, the best of which have well stood the test of time. This impressive collection documents his most fertile period, but the good news is it doesn’t end here: check his website, because he’s still out there on the boards, and may be coming to a town near you soon. Guess what? Not only is he out there, he’s still got it. Get thee hence.