Doubtful Lake from Sahalie Arm (photo posted at Ice Cream For Breakfast)

‘There is nothing like two wills set in opposite directions to determine a woman.’

By Mary Roberts Rinehart

(Ed. note: Though she was more celebrated as a mystery writer [often referred to as the American Agatha Christie–although her first mystery novel preceded Christie’s debut by 14 years–and credited with coining the phrase “the butler did it”–although those exact words did not appear in her novel The Door (1930)–“in which the butler actually did do it, as Wikipedia notes–Mary Roberts Rinehart was as comfortable chronicling the natural world as she was inventing gripping tales out of whole cloth (her supercriminal character The Bat, featured in the stage adaptation of her groundbreaking mystery story of 1908, “The Circular Staircase,” was cited by cartoonist Bob Kane as being one of the chief inspirations for Batman). In 1916 and again in 1918 she published the first and most vivid travelogues of Montana’s Glacier National Park, which had been designated a national park by President William Howard Taft only eight years earlier, on May 11, 1910. Her first Glacier book, Through Glacier Park–Seeing America First with Howard Eaton. (1916; Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company), was a warm account of her journey deep into the park with guide Howard Eaton, whom she describe as “a hunter, a sportsman, and a splendid gentleman” who “takes people with him and puts horses under them and the fear of God in their hearts, and bacon and many other things, including beans, in their stomachs.” Her 1918 bookTenting To-Night, subtitled A Chronicle of Sport and Adventure in Glacier Park and the Cascade Mountains (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company) found her even more daring in accepting the challenges posed by the mountains’ treacherous landscape. In the following excerpt from Tenting To-Night. Mrs. Rinehart describes a grueling hike to Doubtful Lake in the Cascades. Daring came easy to Mrs. Rinehart: in 1915, at age 38 and with three children, she became the first female war correspondent when the Saturday Evening Post sent her to Europe to cover World War I [in Belgium she was received by King Albert, who gave her his first authorized statement regarding the war]. Wherever her interests took her, she remained true to the credo she articulated in the foreword to Through Glacier Park, to wit:

There are many to whom new places are only new pictures. But, after much wandering, this thing I have learned, and I wish I had learned it sooner: that travel is a matter, not only of seeing, but of doing. It is much more than that. It is a matter of new human contacts. It is not of places, but of people. What are regions but the setting for life? The desert, without its Arabs, is but the place that God forgot. To travel, then, is to do, not only to see. To travel best is to be of the sportsmen of the road. To take a chance, and win; to feel the glow of muscles too long unused; to sleep on the ground at night and find it soft; to eat, not because it is time to eat, but because one’s body is clamoring for food; to drink where every stream and river is pure and cold; to get close to the earth and see the stars–this is travel.)

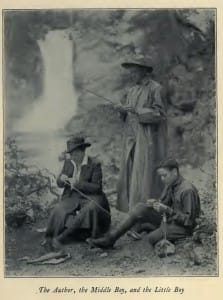

From Tenting To-Night: The Author, the Middle Boy, and the Little Boy

Of all the mountain-climbing I have ever done the switchback up to Doubtful Lake is the worst. We were hours doing it. There were places when it seemed no horse could possibly make the climb. Back and forth, up and up, along that narrow rock-filled trail, which was lost here in a snow-bank, there in a jungle of evergreen that hung out from the mountain-side, we were obliged to go. There was no going back. We could not have turned a horse around, nor could we have reversed the pack-outfit without losing some of the horses.

Of all the mountain-climbing I have ever done the switchback up to Doubtful Lake is the worst. We were hours doing it. There were places when it seemed no horse could possibly make the climb. Back and forth, up and up, along that narrow rock-filled trail, which was lost here in a snow-bank, there in a jungle of evergreen that hung out from the mountain-side, we were obliged to go. There was no going back. We could not have turned a horse around, nor could we have reversed the pack-outfit without losing some of the horses.

As a matter of fact, we dropped two horses on that switchback. With infinite labor the packers got them back to the trail, rolling, tumbling, and roping them down to the ledge below, and there salvaging them. It was heart-breaking, nerve-racking work. Near the top was an ice-patch across a brawling waterfall. To slip on that ice-patch meant a drop of incredible distance. From broken places in the crust it was possible to see the stream below. Yet over the ice it was necessary to take ourselves and the pack.

“Absolutely no riding here,” was the order, given in strained tones. For everybody’s nerves were on edge.

Somehow or other, we got over. I can still see one little pack-pony wandering away from the others and traveling across that tiny ice-field on the very brink of death at the top of the precipice. The sun had softened the snow so that I fell flat into it. And there was a dreadful moment when I thought I was going to slide.

Even when I was safely over, my anxieties were just beginning. For the Head and the Juniors were not yet over. And there was no space to stop and see them come. It was necessary to move on up the switchback, that the next horse behind might scramble up. Buddy went gallantly on, leaping, slipping, his flanks heaving, his nostrils dilated. Then, at last, the familiar call–

“Are you all right, mother?”

And I knew it was all right with them–so far.

Three thousand feet that switchback went straight up in the air. How many thousand feet we traveled back and forward, I do not know.

But these things have a way of getting over somehow. The last of the pack-horses was three hours behind us in reaching Doubtful Lake. The weary little beasts, cut, bruised, and by this time very hungry, looked dejected and forlorn. It was bitterly cold. Doubtful Lake was full of floating ice, and a chilling wind blew on us from the snow all about. A bear came out on the cliff-face across the valley. But no one attempted to shoot at him. We were too tired, too bruised and sore. We gave him no more than a passing glance.

It had been a tremendous experience, but a most alarming one. From the brink of that pocket on the mountain-top where we stood the earth fell away to vast distances beneath. The little river which empties Doubtful Lake slid greasily over a rock and disappeared without a sound into the void.

Until the pack-outfit arrived, we could have no food. We built a fire and huddled round it, and now and then one of us would go to the edge of the pit which lay below to listen. The summer evening was over and night had fallen before we heard the horses coming near the top of the cliff. We cheered them, as, one by one, they stumbled over the edge, dark figures of horses and men, the animals with their bulging packs. They had put up a gallant fight.

This photo from the National Parks Service shows Mary Roberts Rinehart on the lead horse of a pack team near the summit of one of the mountains in the North Cascades.

And we had no food for the horses. The few oats we had been able to carry were gone, and there was no grass on the little plateau. There was heather, deceptively green, but nothing else. And here, for the benefit of those who may follow us along the trail, let me say that oats should be carried, if two additional horses are required for the purpose-carried, and kept in reserve for the last hard days of the trip.

The two horses that had fallen were unpacked first. They were cut, and on their cuts the Head poured iodine. But that was all we could do for them. One little gray mare was trembling violently. She went over a cliff again the next day, but I am glad to say that we took her out finally, not much the worse except for a badly cut shoulder. The other horse, a sorrel, had only a day or two before slid five hundred feet down a snow-bank. He was still stiff from his previous accident, and if ever I saw a horse whose nerve was gone, I saw one there-a poor, tragic, shaken creature, trembling at a word.

That night, while we lay wrapped in blankets round the fire while the cooks prepared supper at another fire near by, the Optimist produced a bottle of claret. We drank it out of tin cups, the only wine of the journey, and not until long afterward did we know its history-that a very great man to whose faith the Northwest owes so much of its development had purchased it, twenty-five years before, for the visit to this country of Albert, King of the Belgians.

That claret, taken so casually from tin cups near the summit of the Cascades, had been a part of the store of that great dreamer and most abstemious of men, James J. Hill, laid in for the use of that other great dreamer and idealist, Albert, when he was his guest. While we ate, Weaver said suddenly,-

“Listen!”

His keen ears had caught the sound of a bell. He got up.

“Either Johnny or Buck,” he said, “starting back home!”

Then commenced again that heart-breaking task of rounding up the horses. That is a part of such an expedition. And, even at that, one escaped and was found the next morning high up the cliffside, in a basin.

Pi-ta-mak-an, or Running Eagle (Mrs. Rinehart), with two other members of the Blackfoot Tribe (from Tenting To-Night)

It was too late to put up all the tents that night. Mrs. Fred and I slept in our clothes but under canvas, and the men lay out with their faces to the sky.

Toward dawn a thunder-storm came up. For we were on the crest of the Cascades now, where the rain-clouds empty themselves before traveling to the arid country to the east. Just over the mountain-wall above us lay the Pacific Slope.

The rain came down, and around the peaks overhead lightning flashed and flamed. No one moved except Joe, who sat up in his blankets, put his hat on, said, “Let ‘er rain,” and lay down to sleep again. Peanuts, the naturalist’s horse, sought human companionship in the storm, and wandered into camp, where one of the young bear-hunters wakened to find him stepping across his prostrate and blanketed form.

Then all was still again, except for the solid beat of the rain on canvas and blanket, horse and man.

It cleared toward morning, and at dawn Dan was up and climbed the wall on foot. At breakfast, on his return, we held a conference. He reported that it was possible to reach the top-possible but difficult, and that what lay on the other side we should have to discover later on.

A night’s sleep had made Joe all business again. On the previous day he had been too busy saving his camera and his life-camera first, of course-to try for pictures. But now he had a brilliant idea.

“Now see here,” he said to me; “I’ve got a great idea. How’s Buddy about water?”

“He’s partial to it,” I admitted, “for drinking, or for lying down and rolling in it, especially when I am on him. Why?”

“Well, it’s like this,” he observed: “I’m set up on the bank of the lake. See? And you ride him into the water and get him to scramble up on one of those ice-cakes. Do you get it? It’ll be a whale of a picture.”

“Joe,” I said, in a stern voice, “did you ever try to make a horse go into an icy lake and climb on to an ice-cake? Because if you have, you can do it now. I can turn the camera all right. Anyhow,” I added firmly, “I’ve been photographed enough. This film is going to look as if I’d crossed the Cascades alone. Some of you other people ought to have a chance.”

But a moving-picture man after a picture is as determined as a cook who does not like the suburbs.

I rode Buddy to the brink of the lake, and there spoke to him in friendly tones. I observed that this lake was like other lakes, only colder, and that it ought to be mere play after the day before. I also selected a large ice-cake, which looked fairly solid, and pointed Buddy at it.

Then I kicked him. He took a step and began to shake. Then he leaped six feet to one side and reared, still shaking. Then he turned round and headed for the camp.

By that I was determined on the picture. There is nothing like two wills set in opposite directions to determine a woman. Buddy and I again and again approached the lake, mostly sideways. But at last he went in, took twenty steps out, felt the cold on his poor empty belly, and-refused the ice-cake. We went out much faster than we went in, making the bank in a great bound and a very bad humor–two very bad humors.