Claudio Monteverdi (15 May 1567-29 November 1643): ‘I found as subject for my music the two contrary passions of battle and prayer on the point of death.’

Italian composer, gambist, and singer Claudio Giovanni Monteverdi is often regarded as revolutionary in that his work marked the transition from the Renaissance style of music to that of the Baroque period. He developed two individual styles of composition–the heritage of Renaissance polyphony and the new basso continuo technique of the Baroque. Monteverdi wrote one of the earliest operas, L’Orfeo, and was recognized as an innovative composer and enjoyed considerable fame in his lifetime. The following observations are from the preface to his 1938 book of Madrigals, Madrigali guerrieri, et amorosi con alcuni opuscoli in genere rappresentativo, che saranno per brevi episodi fra i canti senza gesto or Madrigals of War and Love.)

Reflection shows the principal emotions of mankind to be three: anger, equanimity, and supplication or humility. This truth is corroborated by what the great philosophers say, as well as by the character of the human voice with its high, low, and middle pitch. It is further manifested clearly in the art of sound through its threefold expressions–passionate, soft, and calm. But thought I have carefully searched the works of earlier composers, I have not been able to find any examples of the passionate style–only of the calm and soft. Yet Plato speaks of the agitated style in the third book of his Republic when he describes “that kind of harmony which fittingly imitates the voice and accents of a brave man going into battle.”

Now I am aware that contrasts are what stir our souls, and that such stirring is the aim of all good music. As Boethius puts it: “Music was given us either to purify or to degrade our conduct.” Accordingly, I set about by study and effort to rediscover this style of expression, and finding that all the best philosophers declare that a Pyrrhic, that is to say, a rapid, tempo should be used for all war-like or agitated dances, and on the contrary a slow tempo for the opposite situations, I pondered the repeated quarter note, which seemed to me to correspond to a spondee when performed by an instrument. And when I reduced this note to sixteenths, and matched these one-to-one with a speech connecting anger and disdain, I could hear in this simple example the likeness of the effect I was seeking–and this even though the voice could not keep pace with the speed of the instrument.

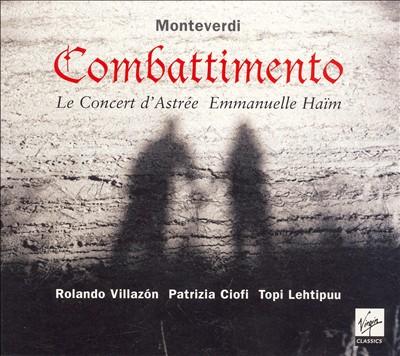

Monteverdi’s Il Combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda (1638). Patrizia Ciofi, Topi Lehtipuu, Rolando Villazón with Le Concert d’Astree under the direction of Emmanuelle Haim (see review below)

In order to test the device still further, I had recourse to the divine Tasso, as being the poet who expresses most aptly and most naturally in words the passions he wishes to describe. I turned to the account he gives of the combat between Tancred and Clorinda [Note: in the twelfth canto of Jerusalem Delivered.] and there I found as subject for my music the two contrary passions of battle and prayer on the point of death.

In the year 1624 I offered my work [Note: The famous Combattimento, with its groundbreaking use of effective tremelos and pizzicati.] for a hearing by the noblest citizens of Venice at the house of the Honorable Gerolamo Mozzenigo, knight and notable of the Venetian Republic, who is my special patron and protector. I was heard, much applauded, and praised.

My principles having met with success in the imitation of anger, I pursued my investigations by further diligent study and produced divers compositions, both sacred music and chamber works, which were so successful in point of style that other composers praised them not only in words but also in their writings, by imitating my technique in their own works, to my great honor and joy.

–Preface to Madrigals of War and Love (1638)

Monteverdi’s Combattimento: Perspectives

Il combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda is an operatic scena for three voices by Claudio Monteverdi, although many dispute how the piece should be classified. The piece has a libretto drawn from Torquato Tasso’s La Gerusalemme Liberata (“Jerusalem Delivered,” Canto XII, 52-62, 64-68), a Romance set against the backdrop of the First Crusade. Il Combattimento was first produced in 1624 but not printed until 1638, when it appeared with several other pieces in Monteverdi’s eighth book of madrigals (written over a period of many years).

In Il Combattimento the orchestra and voices form two separate entities. The strings are divided into four independent parts instead of the usual five–an innovation that was not generally adopted by European composers until the 18th century.

Il combattimento contains one of the earliest known uses of pizzicato in baroque music, in which the players are instructed to set down their bows and use two fingers of their right hand to pluck the strings. It also contains one of the earliest uses of the string tremolo, in which a particular note is reiterated as a means of generating excitement. This latter device was so revolutionary that Monteverdi had considerable difficulty getting the players of his day to perform it correctly. These innovations, like the fourfold division of the strings, were not taken up by Monteverdi’s contemporaries or immediate successors.

‘…imposing in its length and operatic theatricality’

Monteverdi: Combattimento

Emmanuelle Haim, conductor

Virgin Classics

In recent years, Emmanuelle Haïm has achieved prominence at the helm of several baroque operas, including Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo and Handel’s Rodelinda and Giulio Cesare.

Her dramatic bent is well in tow in this anthology of vocal chamber music from Monteverdi’s seventh and eighth book of madrigals, the Scherzi Musicali and assorted anthologies from the 1620s and 1630s. The eponymous work on the recording, the “Combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda” is imposing in its length and operatic theatricality and the most impressive performance on the recording. A treatment of a scene from Tasso’s Gerusalemme liberata in which Christian hero (Tancredi) fights and slays his Saracen beloved (Clorinda), who is traveling incognita in the armor of a male warrior, the work gives ample room for Monteverdi to display both his innovative stile concitato (agitated style), bringing the sounds of battle to life through rapidly articulated tremolos, and his sensitive touch in the dying words of Clorinda. The narrator, Mexican tenor Rolando Villazón, is stunningly dramatic with an Orfeo-like expressive range and responsiveness that both touches and invigorates. And Patrizia Ciofi’s rendition of Clorinda’s last words are movingly poignant and sublime.

In some pieces, however, the intense dramatic singing characteristic of the Combattimento serves less well. The airs “Si dolce è ‘l tormento,” “Perchè se m’odiavi,” and “Maledetto sia l’aspetto” seem overwhelmed by singing that is too vibrant, too inflected, and too intense, where a simpler naturalness might have served the melodic airiness better. Admittedly, the texts are poems of cruel love, and there is much that might invite the dramatic touch, but at the same time, too much drama can rob a beautiful melody of its tuneful grace. This seems to be the case here. And the tenor duet, “Tornate, o cari baci,” has a vibrancy that rather hints of nineteenth-century sound ideals, an echo perhaps of Villazón’s mainstream opera career. Where high drama and intensity of expression are wanted, the two tenors have a great deal to offer. However, with simpler, more tuneful pieces, a less vocally and dramatically encumbered approach would be more compelling.

The instrumental playing is superb. The concitato passage work is thrillingly energized, while elsewhere the characteristicly wafting lilt of sculpted phrases invites one into a richness of sound that is unflaggingly captivating (as in the opening sinfonia of “Tempro la cetra.” Additionally, the opening sinfonia to “Si dolce è ‘l tormento” is a wonderful display of plucked string sound that, too, has unyielding allure. Haïm deploys her diverse forces schematically in a way that well serves the unfolding of the text, an operatic instinct perhaps, and one that is a particularly rich aspect of the recording. –Steven Plank, originally published in Opera Today, October 6, 2008

From the album Combattimento, Monteverdi’s tenor duet ‘Tornate, o cari baci’ has a vibrancy that rather hints of nineteenth-century sound ideals. Featuring Rolando Villazon and Topi Lehtipuu.

‘…an exciting narrative of war, death and forgiveness’

This surprising CD may cause some raised eyebrows from Monteverdi purists, but they are sure to be taken in and convinced by the performances. Emmanuelle Haim is an early-Baroque specialist who believes in a full-bodied approach to the repertoire–no white-voiced, lightly-touching-the-music for her–and she makes it work without ever distorting or going against what is on the printed page. This recording is her boldest yet. Haim uses the warm-toned young tenor Rolando Villazon and soprano Patrizia Ciofi, both known for their roles in 19th-century opera, and Topi Lehtipuu, a fuller-voiced tenor than usual for Monteverdi in some of the composer’s most dramatic works, and each comes brilliantly to life. The long Il combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda is an exciting narrative of war, death, and forgiveness. With Villazon as the narrator and Haim’s instrumentalists offering big-boned playing, the result is almost cinematic. The shorter pieces are just as effective, with Patrizia Ciofi’s expressive “Ohimé” opening the mock lament “Ohimé ch’io cado” with remarkable emphasis and Topi Lehtipuu as involved and musical in his solos as he is duetting with Villazon. This CD will make early-music people appreciate operatic voices and opera lovers pay more attention to 17th-century music. A breathtaking disc. –Robert Levine at amazon.com